Victims of crime often experience negative physical, emotional, and financial consequences. It is essential to understand the various needs of victims and how different types of services can most effectively support them. There are a range of programs and services available for victims, but how do we know what works for whom and what is most effective? Although stakeholders may implement programs with the best intentions, using seemingly reasonable approaches, programs may ultimately have no effect on victims or even cause them unanticipated harm.

Evaluations of programs and practices can give us the data and information we need to understand whether, how, and for whom a program works. They also play a critical role in guiding policymakers and funding organizations, program providers, and other stakeholders as they make important decisions such as whether to continue, revise, or expand an existing program — or pursue other practices.[1] Evaluations enable stakeholders to make better judgments about strengthening the quality of services, improving outcomes, and allocating resources. They increase accountability and transparency in program implementation.

This article explores two types of evaluations — formative and process — describing when they should be used and what they should include. It then discusses three formative and process evaluations funded by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) that examined technology-based victim service programs. These evaluations provide important information about program operations, implementation, research capacity, resources, and victim populations served, and they offer guidance for subsequent evaluations.

Types of Evaluations

The Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 defines evaluation as an “assessment using systematic data collection and analysis of one or more programs, policies, and organizations intended to assess their effectiveness and efficiency.”[2] Evaluations provide insights about the core aspects of a program, describe how it is being implemented, identify areas for improvement, and determine whether it is having the intended effects.

Programs at every implementation stage can benefit from evaluations, identifying initial successes and challenges, allowing for early monitoring and modifications, and providing information about short- and long-term outcomes for victims.[3] There are four types of evaluations for different stages throughout a program’s implementation — formative, process, outcome, and impact. This article focuses on formative and process evaluations.

Formative Evaluation

Stakeholders typically conduct a formative evaluation early in a program’s development and implementation in order to guide program improvement. A formative evaluation addresses whether a program is feasible, appropriate, and acceptable for its intended purpose, context, and population of interest.[4] It allows for necessary changes to be made early, thus increasing the likelihood of program success.

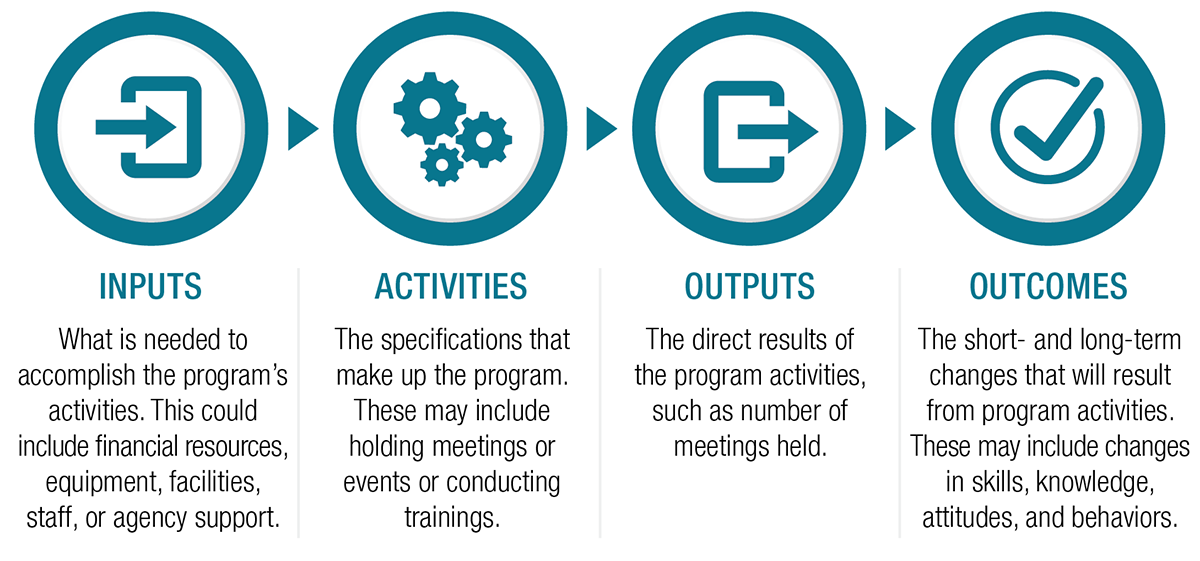

Formative evaluations typically include descriptive research about the program, development of a logic model, and evaluability assessments.[5] A logic model visually depicts how a program is expected to work and achieve its goals. It shows the program’s roadmap specifying the inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes (see exhibit 1). An evaluability assessment shows the extent to which a rigorous evaluation is justified and feasible. It explores whether an evaluation is likely to provide useful information by analyzing the program’s goals, objectives, and operations, as well as the capacity for data collection, management, and analysis. A key step in evaluability assessments involves examining the availability and use of data to explore evaluation designs. To determine the extent to which the program results in any outcomes, evaluation plans must include sufficient sample sizes and a counterfactual (such as a comparison or control group) to estimate what is likely to happen if the program is not introduced.[6]

Exhibit 1: Program Evaluation Logic Model

Process Evaluation

Process evaluations, also referred to as implementation evaluations, investigate whether the program is being implemented as designed. They can occur periodically throughout the program to understand how well the program is working operationally. A process evaluation also identifies potential facilitators or barriers to implementation and provides information for program improvements.

NIJ has supported evaluations of a range of programs that deliver services to victims of crime. The Institute uses a phased approach to evaluate the effectiveness of victim services; it involves supporting projects in discrete and successive evaluation phases depending on the stage of program development. In fiscal year 2018, NIJ funded three projects that included formative and process evaluations examining technology-based victim services.

Evaluation of Technology-Based Advocacy Services

NIJ-funded researchers at the University of Texas at Austin partnered with the local organization The SAFE Alliance to conduct a formative evaluation of its SAFEline program.[7] The SAFE Alliance provides various services for adult and youth victims of crime and violence, including sexual assault and exploitation, intimate partner violence, human trafficking, and child abuse and neglect. The SAFEline hotline service provides 24/7 phone, chat, and text support for crime victims and offers crisis intervention, safety planning, emotional support, screening for admission to services, and information and referrals.

The project team sought to understand program use, victims’ needs and experiences, and necessary resources for implementation and subsequent evaluations. They collected and analyzed SAFEline program documents and data, surveyed SAFEline program users, conducted a literature review, and interviewed staff as well as prospective and past program users.

The researchers found that the SAFEline service model and approach were user-centered (service users engage with advocates on their self-defined goals at their own pace), trauma-informed (advocates center the role of trauma in their interactions with service users), social justice-oriented (advocates respect cultural factors in program design, referrals, and advocacy), and social presence-facilitated (advocates use individualized responses for unique situations).

The researchers found that since 2018, SAFEline completed an average of 18,735 call, chat, and text sessions per year. When surveyed, the majority of SAFEline service users reported that their primary goal in contacting SAFEline was to obtain help with counseling (49.7%) or housing (43.3%). Interviews and reviews of chat and text transcripts showed that service users most often expressed need for housing, legal advocacy, and counseling or emotional support. Most users (82.9%) reported being satisfied with the amount of time that SAFEline advocates spent with them.

The team produced a logic model with five goals that guide technology-based advocacy and key skills associated with each goal. The short- and long-term outcomes included increased safety, reduced isolation, and increased resource knowledge. The team also identified several barriers to successful chat or hotline interactions, including lack of access to and comfort with the platform; delayed response times (for example, in getting connected with an advocate); misaligned communication approaches (for example, the advocate is perceived as dismissive); and service inaccessibility due to high demand for interpersonal victim services. During interviews, SAFEline staff and service users offered recommendations to address these barriers, including partnering with community organizations, increasing staffing at high-volume outreach times, and improving communication strategies (for example, advocates using strengths-based language).

The researchers observed that chat and text hotlines are crucial to service availability for crime victims because they provide immediate crisis services and function as a supportive space for victims. They also noted that local hotlines, such as SAFEline, extend the benefits of national hotlines by connecting users to local support and teaching victims how to access help. In addition, preliminary analyses of SAFEline service use data showed that chat and text services increased access to teens and young adults, Spanish-speaking service users, and individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing.

For the evaluability assessment, researchers examined program function and quality, agency capacity, resources, and the feasibility of collecting data. After confirming these necessary factors were in place and adequate, they established that SAFEline is a strong candidate for an outcome evaluation. The researchers stated that the next phase will be a longitudinal, mixed methods, multi-site evaluation that aims to assess short- and long-term outcomes of technology-based advocacy for survivors of interpersonal violence.[8]

Evaluation of a Technology-Based Behavioral Health Program

In the second NIJ-funded study, researchers at RTI International partnered with El Futuro to conduct a formative and process evaluation of TeleFuturo.[9] El Futuro is a nonprofit organization in North Carolina that provides bilingual and culturally informed behavioral health treatment for underserved Spanish-speaking individuals and families, including Latinos and rural residents, many of whom have experienced traumatic events and crimes. El Futuro developed TeleFuturo, a telemental health program, to meet the specific needs of rural clients. It involves a hybrid of telehealth and in-person services (including psychotherapy, psychiatric services, and case management).

The project team sought to understand program implementation, monitor indicators of progress, and assess barriers and facilitators. Researchers reviewed relevant documents and data systems and interviewed El Futuro staff.

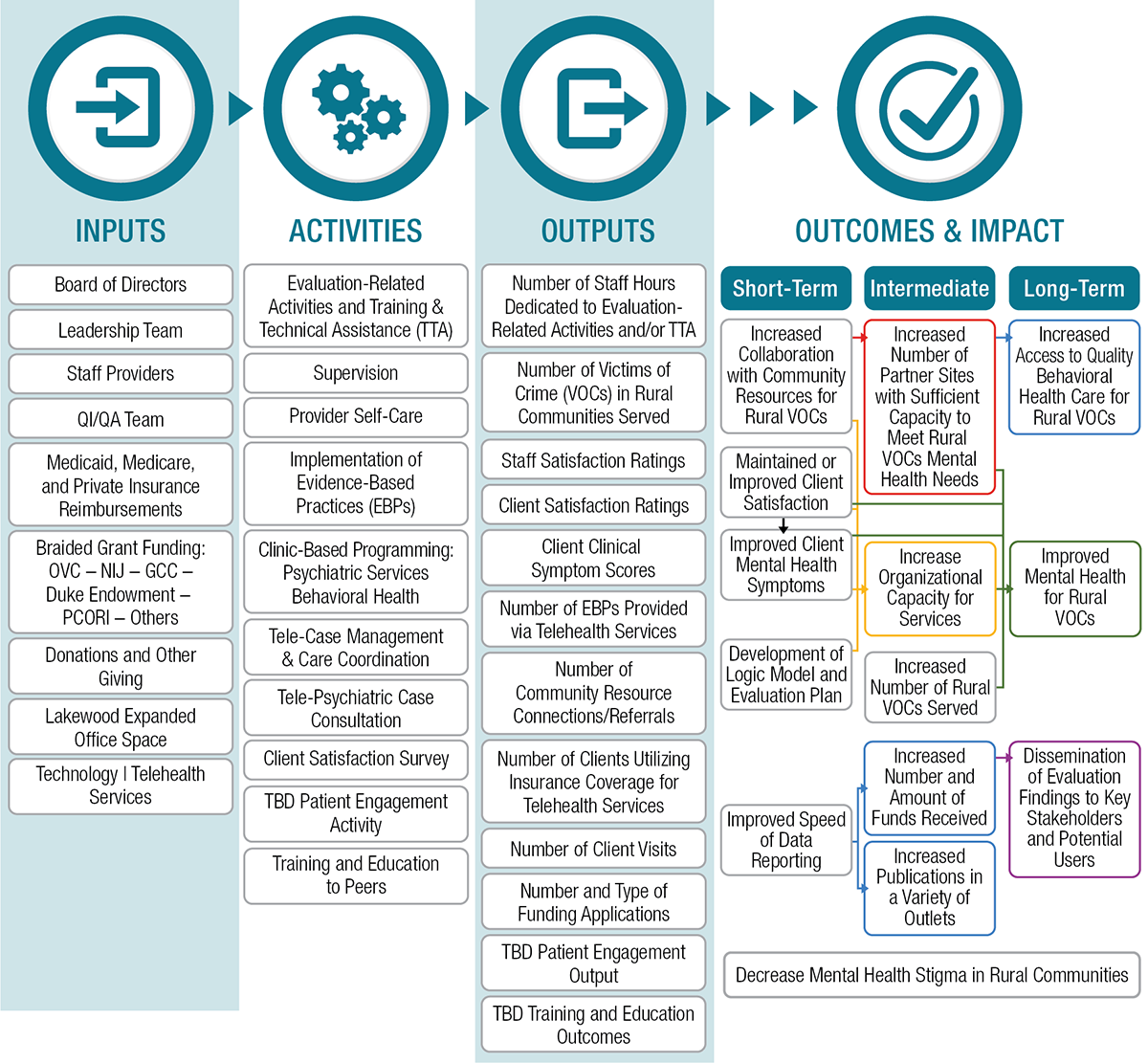

The conceptual framework for TeleFuturo consists of cultural, clinical, and technical competencies and client-centered approaches. The team developed a logic model (see exhibit 2) that focused on telehealth implementation and connected El Futuro’s activities with the intended goals of its telehealth services. Examples of outcomes included short-term improvement in client satisfaction and mental health symptoms and an increased number of partner sites and rural victims served in the intermediate term. Long-term outcomes included increased access to quality behavioral health care for rural victims.

Exhibit 2: TeleFuturo Logic Model

Through interviews with program staff, the researchers found three main challenges in implementing telemental health treatment. First, concerns around confidentiality meant a cultural reluctance to use videoconferencing (for example, for individuals who are undocumented). Second, both providers and clients needed support with the telehealth platform given the unfamiliarity with using the technology, especially with the rapid transition to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many rural clinics also faced technical challenges, such as internet bandwidth issues.

Lastly, there were clinical factors. Some clients lacked a private, secure location for telehealth services, and providers faced difficulties engaging clients without the ability to check vital signs and perform other treatments. However, therapists reported that teletherapy did address some barriers to care, such as transportation issues and lack of childcare, and that some clients responded better to or preferred telehealth. Understanding these factors was helpful in thinking about how to improve services. Providers could reassure clients about confidentiality and have support staff, such as telehealth coordinators, provide technological and scheduling help.

The researchers concluded that TeleFuturo possessed the components for a successful telehealth intervention for a range of victims. Pilot data from client satisfaction surveys and depression, anxiety, and stress scales showed that many victims noted improved mental health symptoms, and most indicated high satisfaction with TeleFuturo.

The evaluability assessment sought to assess whether El Futuro’s current approach could answer questions about program design, implementation needs, and the data collection procedures needed for an adequate and informed evaluation. Interviews with key stakeholders, document reviews, and an examination of El Futuro’s data systems showed that TeleFuturo is an evaluable program ready for a phase 2 process evaluation. The researchers based this determination on an assessment of staff capacity to implement services, the development of an implementation guide to assist in replication and measuring fidelity, and the development of reliable instruments to measure outcomes.[10]

Evaluation of Referral and Helpline Services

In the final NIJ-funded study, researchers at the Urban Institute partnered with the National Center for Victims of Crime (NCVC) to conduct a formative evaluation of the VictimConnect Resource Center.[11] The VictimConnect Resource Center, funded by the Office for Victims of Crime and operated by NCVC, is the nation’s only resource center that offers comprehensive referral information and helpline services to victims of all crime types and their loved ones. VictimConnect provides services through four technological modalities: (1) softphone (internet-based phone calls), with the option for a warm handoff to an external service provider;[12] (2) online chat with a victim assistance specialist; (3) text messaging with a victim assistance specialist; and (4) informational resources on the website.

The project team sought to understand VictimConnect’s operations, research capacity, and resources, and how it provides service access and delivery. The team reviewed the relevant literature; examined documentation, program materials, and aggregated data collected by NCVC; and interviewed VictimConnect stakeholders.

The formative evaluation uncovered that VictimConnect has fielded more than 40,000 interactions since 2015. VictimConnect visitors reported a wide variety of victimization experiences, with the most common experiences being stalking, identity theft and fraud, harassment, intimate partner violence, cybercrime, assault/attempted homicide, abuse of older adults, domestic violence, and mass violence events.[13] Most visitors sought information on local service providers. Each time a victim assistance specialist provided resources, they included at least two referrals to local and national resources and providers, as well as an explanation about the services and how they might help. For example, a victim assistance specialist may explain to a visitor what a protective order is and what a victim witness assistance office can do. Visitors also sought information about financial assistance or victim compensation, crime reporting, legal services, case management or victim advocacy, safety planning, hotlines or related referral services, and other general VictimConnect resource information.

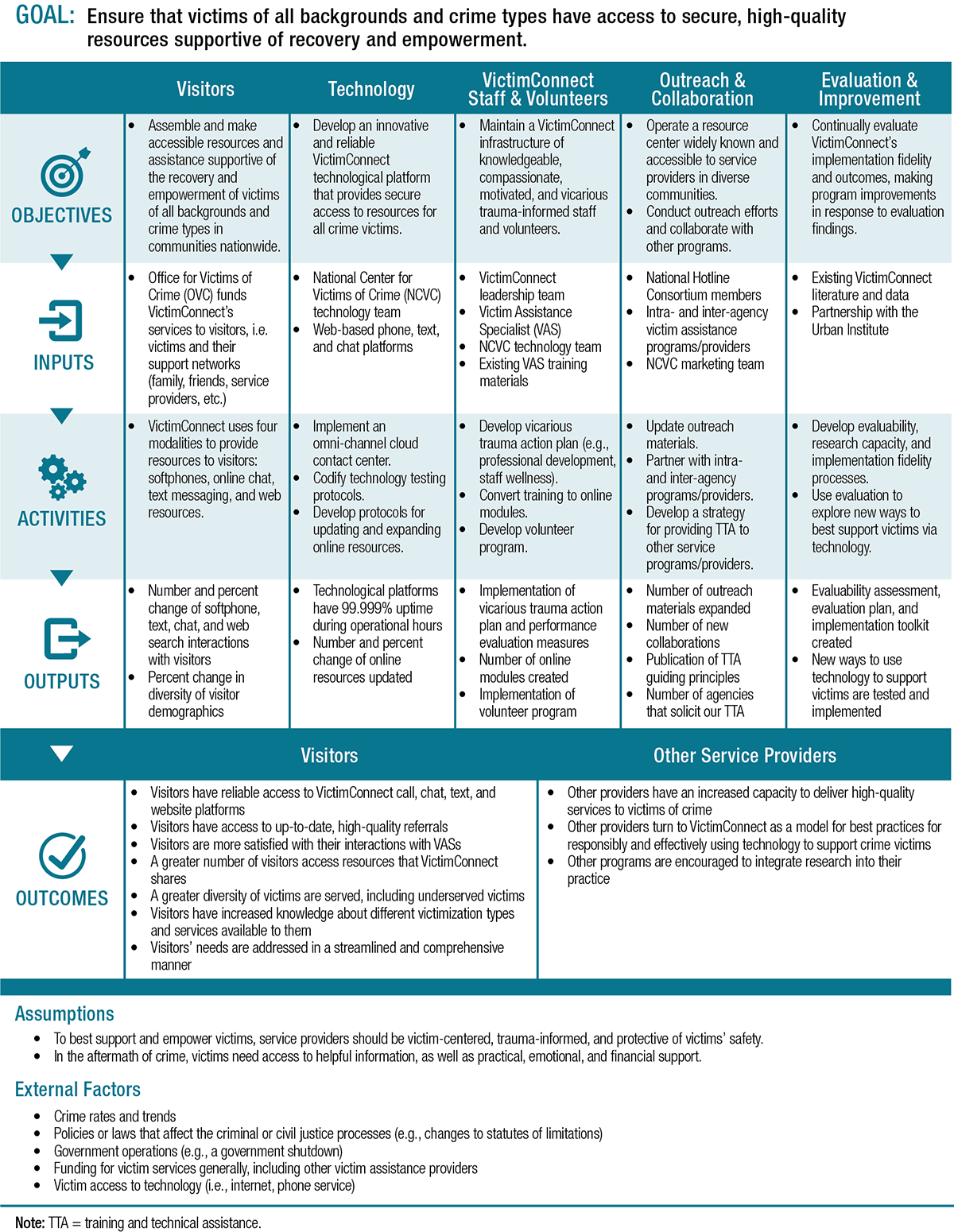

The team produced a revised logic model (see exhibit 3) to understand VictimConnect’s overarching components, guide program improvements and other operational changes, and inform strategic planning. They divided outcomes into those related to visitors, such as satisfactory interactions with victim assistance specialists and greater diversity of victims served, and to service providers, such as increased capacity to deliver high-quality services.

Exhibit 3: VictimConnect Logic Model

The team also worked with NCVC staff to identify opportunities to build VictimConnect’s research capacity. These included activities such as revising training protocols and developing quality-control rubrics, upgrading the technology to support enhanced supervisory and research capabilities, and expanding analysis of performance measures. This focus on building research capacity will help the program better meet victims’ needs and prepare for a future comprehensive implementation evaluation and a rigorous outcome evaluation.

Findings from this formative evaluation suggest that VictimConnect has an extensive reach across the nation and serves a sizable and diverse number of visitors. The evaluability assessment involved close collaboration with NCVC to understand program operations and identify helpful changes, refine the programmatic logic model, improve data sources, explore program challenges, and plan the most rigorous evaluation design feasible. The research team also explored potential comparison groups against which VictimConnect visitors’ outcome information should be compared. After consulting with service provider staff and the project advisory board, they determined that “after-hour visitors,” or people who reach out to VictimConnect before or after its hours of operation, would be the most promising and relevant comparison group. Based on these activities and discussions, researchers found that an outcome evaluation of VictimConnect would be feasible and meaningful.[14]

Next Steps

NIJ-supported formative and process evaluations provide important information about technology-based victim service programs. NIJ recently funded the projects’ researchers to build on the completed formative evaluations and conduct the subsequent phases of evaluations (process[15] and outcome[16]). Findings from additional evaluations will further inform improvements and enhance our understanding about the effectiveness of technology-based services in increasing victim safety and wellbeing.

About the Authors

Yunsoo Park, Ph.D., is a former social science research analyst in NIJ’s Office of Research, Evaluation, and Technology. Erica Howell, M.A., is a social science research analyst in NIJ’s Office of Research, Evaluation, Forensics, and Technology.

About This Article

This article was published as part of NIJ Journal issue number 286. This article discusses the following awards:

- “ETA: Evaluation of Technology-Based Advocacy Services,” award number 2018-ZD-CX-0004

- “Formative Evaluation of a Technology-Based Behavioral Health Program for Victims of Crime,” award number 2018-ZD-CX-0001

- “Phased Evaluation of VictimConnect: An OVC-Funded Technology-Based National Resource Center,” award number 2018-V3-GX-0003