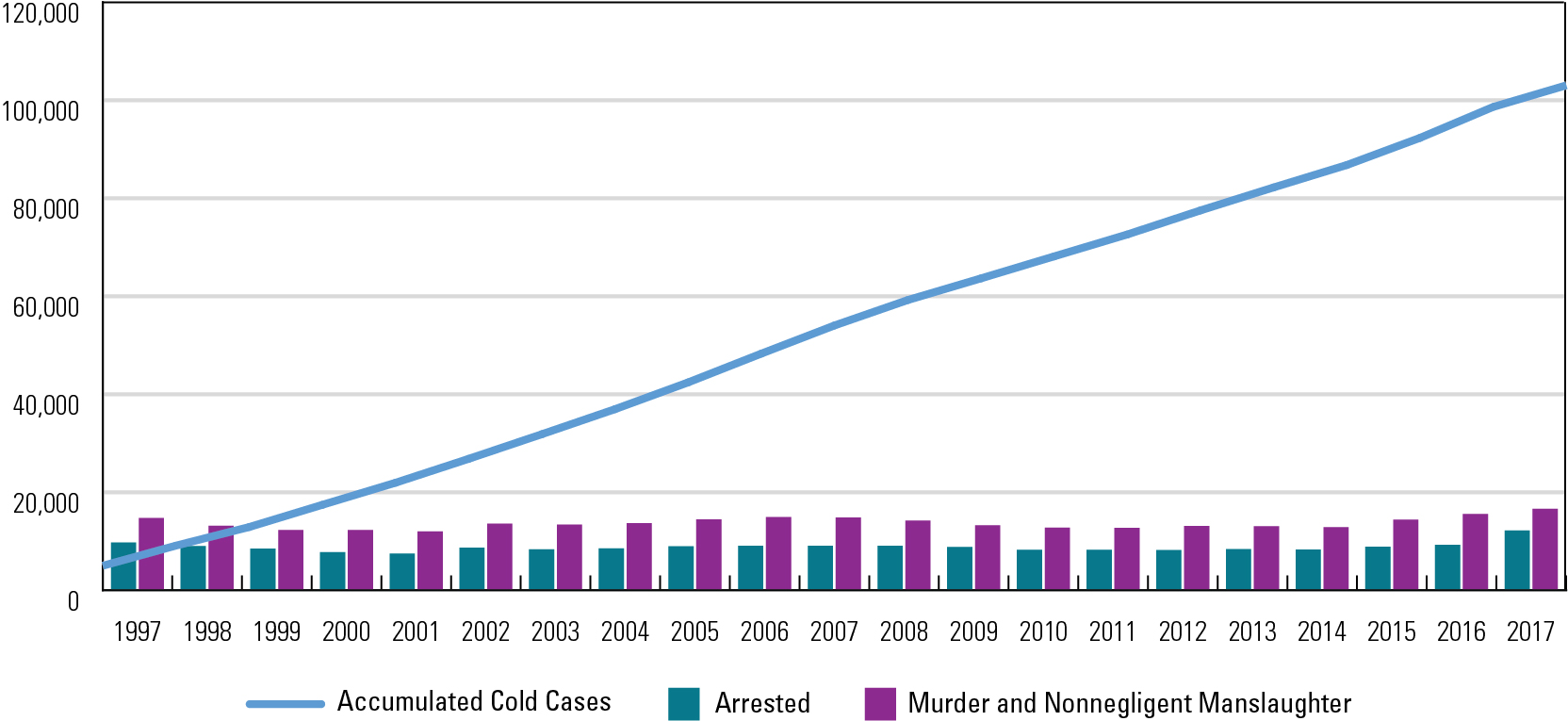

There is a cold case[1] crisis in the United States. In 1965, approximately 80% of homicide cases were cleared, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports, but in 2017 only about 60% of homicide cases were resolved.[2] An estimated 250,000 unresolved homicides exist in the United States, and more than 100,000 have accumulated in the past 20 years alone (see exhibit 1).[3]

| Year | Cases of Murder and Nonnegligent Manslaughter | Percentage Cleared by Arrest | Arrested | Cold Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 14,759 | 66.1% | 9,756 | 5,003 |

| 1998 | 13,134 | 68.7% | 9,023 | 4,111 |

| 1999 | 12,266 | 69.1% | 8,476 | 3,790 |

| 2000 | 12,291 | 63.1% | 7,756 | 4,535 |

| 2001 | 11,982 | 62.4% | 7,477 | 4,505 |

| 2002 | 13,561 | 64.0% | 8,679 | 4,882 |

| 2003 | 13,373 | 62.4% | 8,345 | 5,028 |

| 2004 | 13,662 | 62.6% | 8,552 | 5,110 |

| 2005 | 14,430 | 62.1% | 8,961 | 5,469 |

| 2006 | 14,948 | 60.7% | 9,073 | 5,875 |

| 2007 | 14,811 | 61.2% | 9,064 | 5,747 |

| 2008 | 14,225 | 63.6% | 9,047 | 5,178 |

| 2009 | 13,242 | 66.6% | 8,819 | 4,423 |

| 2010 | 12,760 | 64.8% | 8,268 | 4,492 |

| 2011 | 12,706 | 64.8% | 8,233 | 4,473 |

| 2012 | 13,092 | 62.5% | 8,183 | 4,910 |

| 2013 | 13,075 | 64.1% | 8,381 | 4,694 |

| 2014 | 12,879 | 64.5% | 8,307 | 4,572 |

| 2015 | 14,392 | 61.5% | 8,851 | 5,541 |

| 2016 | 15,556 | 59.4% | 9,240 | 6,316 |

| 2017 | 16,617 | 61.6% | 12,208 | 4,409 |

| TOTAL | 287,761 | 184,700 | 103,061 |

In part, limited resources have caused the crisis. Law enforcement agencies are stretched thin and often lack the personnel to adequately work cases as they happen. Cold cases are also difficult investigations, sometimes because of a lack of evidence. If there were easy solutions, resolution would have occurred at the time of the offense. As time passes, the likelihood of losing case file information, evidence, and witnesses increases.

Another likely contributor to the country’s current cold case crisis is the number of serial killers operating in the United States. A serial murder is the unlawful killing of two or more victims by the same person(s) in separate events.[4] Estimates vary, but one estimate of the number of serial killers in the United States who have never been prosecuted for their crimes was as high as 2,000.[5] Another study suggests that up to 15% of homicides are the result of serial killers.[6] Meanwhile, estimates of the number of victims of serial killers, from a research study out of Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, range from fewer than 200 to almost 2,000 each year.[7] The study notes that quantifying the estimated number of victims is difficult, and generalizing and extrapolating data has created a wide range of estimates — but even the low end of the range is alarming.

NIJ had several robust programs that have helped law enforcement agencies solve cold cases over the years. (Recently, nonresearch support for cold case investigations was transferred to one of NIJ’s sister agencies, the Bureau of Justice Assistance.) In the process, NIJ-sponsored research has discovered a number of important connections between cold cases and those who repeatedly commit crimes, the most alarming of whom are serial killers.

Helping Resolve Cold Cases

NIJ has a long history of supporting the scientific, technical, and capacity needs of the forensic community, particularly as the demand for forensic testing has grown.[8] NIJ recognizes the value of analyzing evidence from older, unresolved cases. From 2005 to 2014, the Institute provided funding for law enforcement agencies to review cold cases and submit their evidence for DNA analyses through its Solving Cold Cases with DNA program. This resulted in the resolution of more than 2,000 cold cases (see exhibit 2).

See “The Costs and Benefits of Cold Cases”

| Year | Number of Awards | Amount of Funding | Number of Cases Reviewed | Number of Cases Where Biological Evidence Remained | Number of Cases Where DNA Was Tested | Number of Cases That Yielded a Profile | CODIS Uploads | CODIS Hits | Number of Cases With Trials, Arrests, Closed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 38 | $14,245,153 | 7,767 | 1,305 | 2,236 | 677 | 704 | 261 | 206 |

| 2007 | 21 | $8,485,130 | 33,897 | 4,174 | 1,573 | 786 | 530 | 158 | 328 |

| 2008 | 42 | $16,119,105 | 50,813 | 7,371 | 3,691 | 2,049 | 1,493 | 576 | 353 |

| 2009 | 27 | $12,263,938 | 14,087 | 6,475 | 2,278 | 1,369 | 956 | 365 | 333 |

| 2010 | 27 | $10,148,219 | 11,885 | 5,522 | 1,711 | 723 | 598 | 248 | 358 |

| 2011 | 11 | $4,355,843 | 7,610 | 3,545 | 640 | 378 | 445 | 197 | 176 |

| 2012 | 22 | $7,580,191 | 9,834 | 4,536 | 1,218 | 497 | 432 | 138 | 245 |

| 2014 | 25 | $4,742,222 | 5,498 | 1,361 | 1,024 | 513 | 422 | 118 | 86 |

| Total | 213 | $77,939,801 | 141,371 | 34,289 | 14,371 | 6,992 | 5,580 | 2,061 | 2,085 |

| Note: Data are reported to NIJ only during the funded project period, and all 213 of the Solving Cold Cases with DNA awards are closed. Most activities related to cold case investigations occur after the grantees no longer provide project progress reports. DNA results and uploads to the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), for example, often happen after the project period. Thus, CODIS hits and closed cases resulting from NIJ-funded projects reported here are considered to be conservatively low. | |||||||||

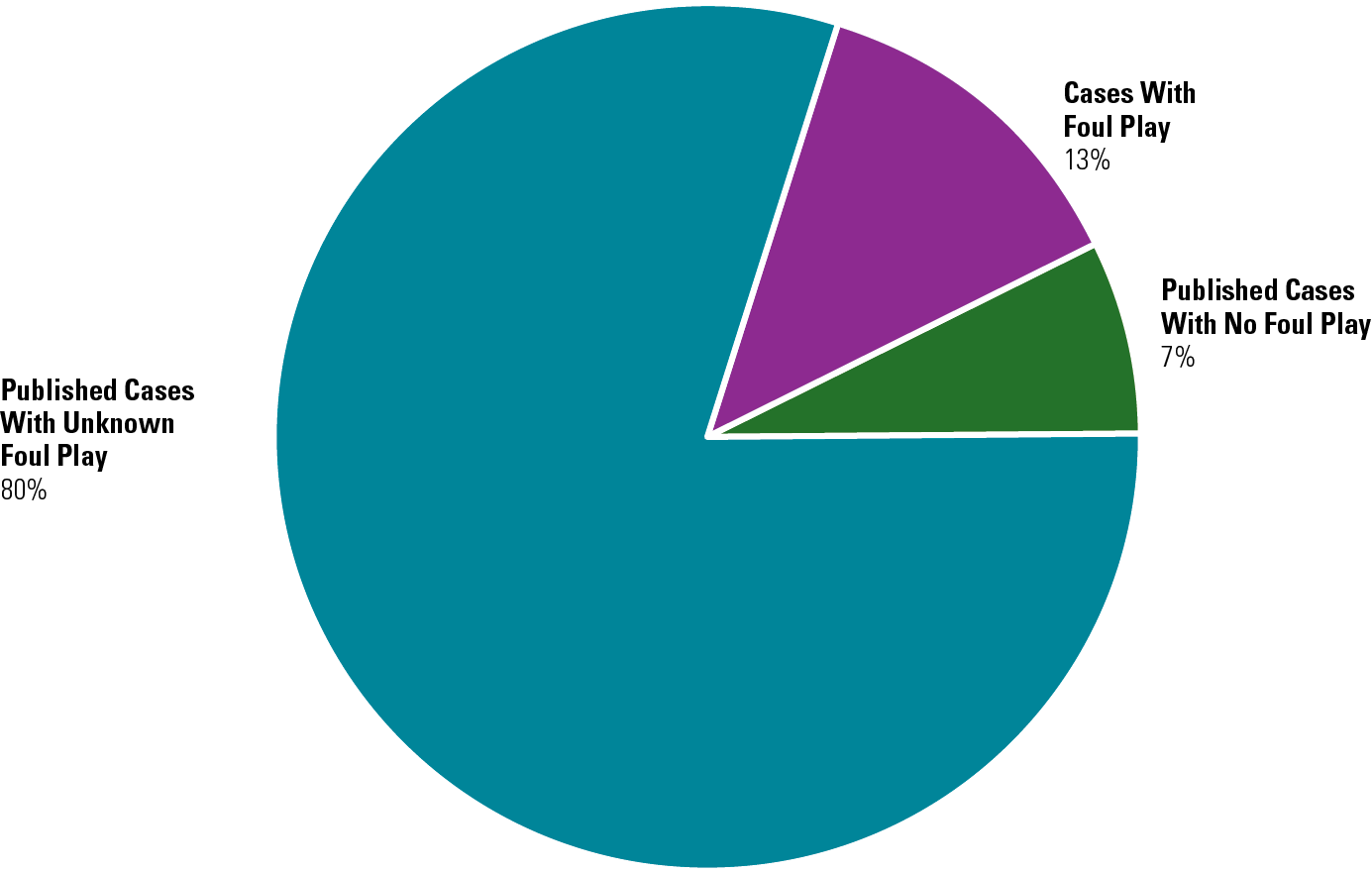

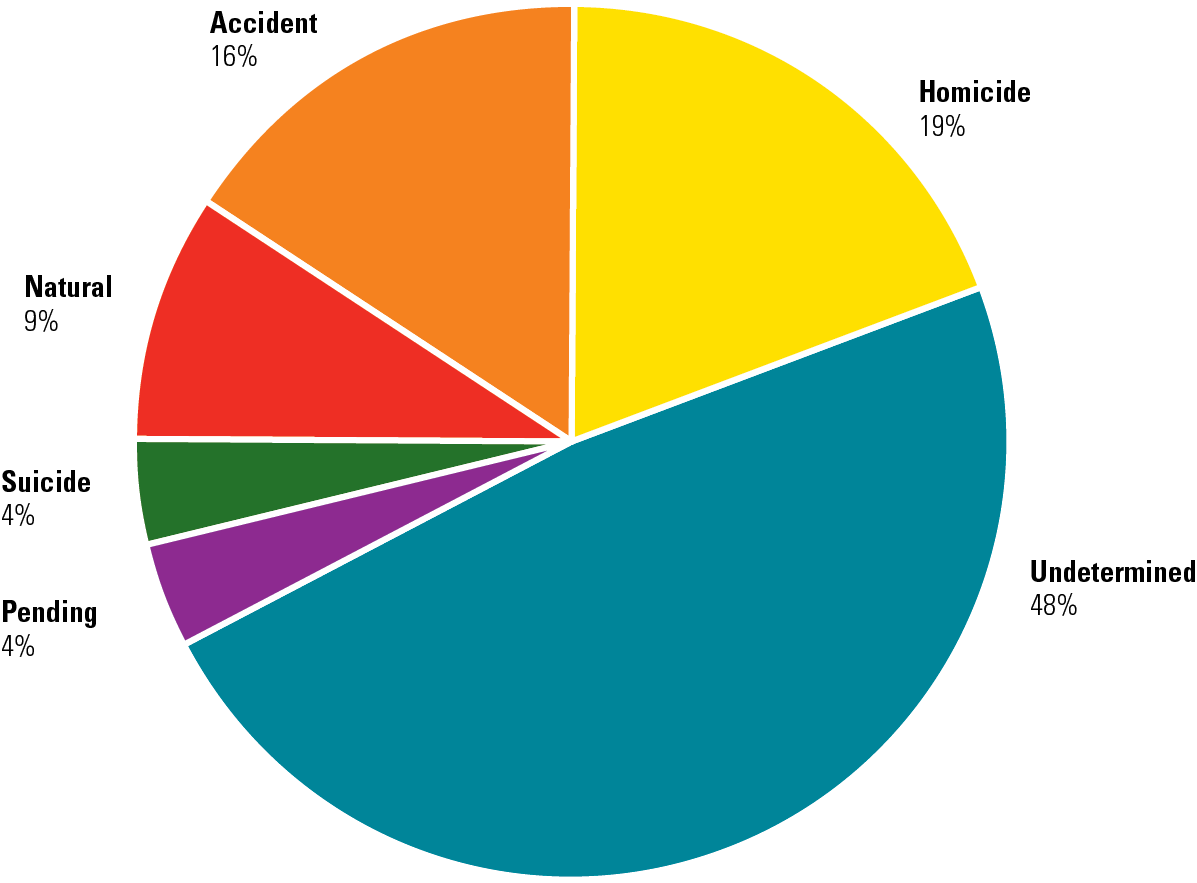

In 2019, NIJ initiated the Prosecuting Cold Cases using DNA and Other Forensic Technologies program.[9] There was also a need to address the growing accumulation of unidentified remains and missing persons cases. As a result, the Using DNA to Identify the Missing program and the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) evolved.[10] As of February 2019, NamUs reports that foul play is not suspected in only 7% (approximately 1,000) of its published missing persons cases (see exhibit 3). The approximately 14,000 remaining cases could have or are suspected to have resulted from foul play, and some fraction of these cases are likely to have serial killer connections. Likewise, some portion of the more than 7,000 unidentified persons cases published in NamUs (comprising more than 2,000 known homicide victims and more than 5,000 unidentified persons whose manner of death remains undetermined) are also likely to be the result of serial killers ( see exhibit 4).

Potentially more staggering is the number of missing persons who are unaccounted for. These people — often immigrants, foster children, and transient people such as homeless individuals and prostitutes — are not reported missing for a variety of reasons. Even when they are reported missing, law enforcement does not routinely investigate such cases until there is cause to believe that foul play has occurred.[11] In interviews, many serial killers have noted that they preyed on these vulnerable populations and disposed of their victims’ bodies in places and manners unlikely to be discovered; thus, their crimes could go unnoticed and they could continue killing.[12]

See “NIJ Programs Help Support Cold Case Investigations”

NIJ’s Role in High-Profile Investigations

Through administration of these NIJ programs, several serial killers[13] and their victims have been identified. Below are a few examples of high-profile serial killer cases that were solved with the assistance of NIJ programs.

Boston Strangler

Albert DeSalvo admitted to killing 13 women in the Boston area between 1962 and 1964. Several of the victims were strangled, thus earning DeSalvo the moniker the “Boston Strangler.” However, DeSalvo recanted his confession of the murder of Mary Sullivan, and controversy arose over his culpability in that case. DeSalvo — sentenced to life in prison in 1967 — was killed in prison in 1973. In 2013, the Boston Police Department used funds from the Solving Cold Cases with DNA program[14] to confirm that DNA recovered from Mary Sullivan was a statistically relevant match to DNA from DeSalvo’s remains, which were exhumed that same year.

Killer Clown

In 1978, 30 bodies were recovered at the Chicago home of John Wayne Gacy, a part-time clown entertainer. As of 2011, 14 victims remained unidentified, but two of those victims have since been identified using forensic technologies. Facial reconstructions performed on the unidentified victims and DNA profiles obtained through NIJ’s Using DNA to Identify the Missing program led to the identification of William Bundy in 2011.[15] In 2017, NamUs assisted in identifying Jimmy Haakenson.[16]

Green River Killer

During the 1980s, Gary Ridgway killed numerous women along the Green River in Washington state. In 2003, Ridgway — called the “Green River Killer” — was convicted of killing 49 women; he is suspected in as many as 90 homicides. In 2001, the King County Sheriff’s Office used DNA laboratory equipment purchased with NIJ funds from the Crime Laboratory Improvement Program to link evidence found on four of the victims to Ridgway.[17]

In addition to not knowing the actual number of Ridgway’s victims, the identities of some victims remain unknown. In 2012, through two separate awards from NIJ’s Using DNA to Identify the Missing program, Bode Cellmark Forensics and the University of North Texas Health Science Center used reference DNA provided by siblings to confirm that the victim once known as “Jane Doe B16” was Sandra Major.[18]

Long Island Killer

Eleven sets of human remains were recovered along a beach in Long Island, New York. Several of the victims were dismembered and only partially recovered. Through NIJ’s Using DNA to Identify the Missing program, New York City’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner helped determine the identities of six victims. It also matched two sets of remains recovered from separate locations to one victim, who remains unidentified.

The medical examiner’s office also obtained a partial familial DNA match between DNA samples collected from two victims found on Long Island and the brother of John Bittrolff. Bittrolff was confirmed as an exact match to the DNA from the victims and was subsequently convicted. His case was the first homicide conviction in New York based on a partial DNA match — although it still remains unclear whether Bittrolff is the “Long Island Killer” or only one of perhaps multiple killers who disposed of their victims in that area.[19]

Grim Sleeper

A single source of DNA connected several homicide victims from the 1980s and 2000s, but no suspect was identified in the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). The lag between the associated killings led to the moniker the “Grim Sleeper.”

NIJ’s Solving Cold Cases with DNA program enabled detectives to review and analyze DNA evidence in several of the unsolved homicides. A familial DNA search in CODIS led investigators to the son of Lonnie David Franklin Jr. NIJ funding assisted in analyzing DNA from Franklin, which was confirmed as a match to DNA recovered from the murders.

In 2016, Franklin was convicted of killing 10 women, and he is suspected of killing an additional 25 women. More than 100 photographs of unknown women were found among Franklin’s possessions, leading to speculation that he may have been responsible for many more killings.[20]

Golden State Killer/East Area Rapist

In the 1970s and 1980s, at least two separate persons committing serial crimes were thought to be operating in California: the “Golden State Killer” and the “East Area Rapist.” These unknown persons were also known as the “Original Night Stalker,” the “Visalia Ransacker,” the “East Bay Rapist,” and the “Diamond Knot Killer.”

Funding through NIJ’s Solving Cold Cases with DNA program helped link a double homicide in Ventura to a common suspect in 10 homicides and three sexual assaults throughout California — including in Orange County, where a separate NIJ award allowed investigators to work on unsolved sexual assaults and homicides attributed to the Golden State Killer and the East Area Rapist.[21] Once investigators from multiple counties realized that the same person was committing the crimes, they calculated that the suspect had possibly committed more than 50 sexual assaults. Armed with the case-to-case connections, investigators tried a new DNA investigative approach: forensic genetic genealogy, which is the identification of suspects through DNA matches to family members. In 2018, Joseph James DeAngelo was identified as a suspect, and a confirmatory DNA match led to 13 rape charges and 13 murder charges against him.

Truck Drivers and Other Cases

Truck drivers travel great distances regularly, which provides ideal opportunities to commit crimes that are difficult to resolve.[22] With funding from NIJ’s Using DNA to Identify the Missing program, the University of North Texas was able to connect truck driver William Reece to the deaths of one girl in Oklahoma and two young women in Texas.

In addition to the high-profile cases listed above, NIJ grantees have reported other serial killers who were identified as a result of their projects.

See a more comprehensive list of serial killer investigations aided by NIJ funds in appendix A.

Catching Those Who Serial Offend Early

Understanding patterns of behavior along with criminal and psychological profiles can help identify and catch prolific serial killers — and perhaps even prevent some before they start. For example, studies have shown that compared to other criminals, serial violent individuals start committing crimes earlier; offend over a longer period of time; and have more employment, interpersonal, and substance abuse problems.[23] Moreover, research suggests that those who engage early on in a diverse criminal career are likely to commit more violent offenses later.[24]

Armed burglary in particular is associated with further increases in violent crime, such as armed robbery, armed rape, kidnapping, assault with intent to murder, and even first-degree murder. Researchers have found that those who commit sex offenses were most likely to transition quickly from conventional profit-motivated burglaries to sexual assaults in homes without engaging in fetish-motivated burglaries or voyeurism.[25]

Some serial killers exhibit a three-part progression from burglary to sexual assault to murder. Sexual assault does not necessarily predict further escalation to violent crime or serial killing,[26] but some examples of this pattern include the following cases:

- Albert DeSalvo (the Boston Strangler) began with shoplifting and stealing. He progressed to burglary and eventually to sexual assault and murder.[27]

- Joseph DeAngelo (the Golden State Killer) committed a string of burglaries from April 1974 to December 1975. He then progressed to a series of sexual assaults between June 1976 and July 1979 and was dubbed the “East Area Rapist.” He progressed to murder in October 1979 and was called the “Original Night Stalker” before investigators finally linked him to the burglaries, sexual assaults, and homicides.[28]

- John Wayne Gacy (the Killer Clown) engaged in petty theft as a child, graduated to sexual assault in his 20s, and then began to murder in his 30s, preying on a vulnerable population of teenage boys.[29]

These findings are important because they suggest that the seriousness of any one offense should not drive where law enforcement directs resources for investigating and clearing cases. Such strategies are understandable, but they can lead to the perception that there are classes of individuals who offend based on specialty. This belief, in turn, may lead law enforcement to prioritize cases related to those committing “violent” offenses over cases involving “property” offenses.

It would be worthwhile to reconsider the way agencies investigate cold cases — that is, it would be beneficial to include a wider range of offenses when seeking investigative leads for homicides. Indeed, research on the careers of serial killers justifies paying increased attention to burglaries when investigating violent criminal careers and cold cases.

To help law enforcement understand the nexus of property crimes and more violent offenses, NIJ funded the Urban Institute to conduct a randomized controlled trial examining the impact of using DNA testing to investigate burglary cases in five separate jurisdictions. Researchers found that in 67% of cases in which a DNA sample was obtained, the sample was entered into CODIS; 41% of these cases yielded a match.[30] Overall, this led to twice as many suspects identified when using DNA than through conventional burglary investigations.[31]

Of particular interest, suspects identified through DNA evidence from burglaries had double the number of felony arrests and convictions than suspects identified using conventional methods.[32] This finding does not guarantee that using DNA methods to investigate burglaries will lead law enforcement to individuals committing serial violent offenses (known or unknown), but it does show that these investigative methods help police discover and apprehend more those offend prolifically.

Addressing the Crisis

Focusing investigative efforts on cold cases and apprehending individuals committing repeat offenses can prevent future crimes and protect possible victims, thus saving the community the immense cost of these crimes. Clearing cases also frees agency resources, and resolved crimes equate to a sense of a safer community, lessening the need for “boots on the ground” and reactive policing.

The future looks bleak when seeing numbers like a quarter of a million unresolved homicides and 2,000 serial killers. But today’s agencies have numerous tools on their side, including research on best investigative practices, advancements in science and technology, and increased information exchange. As evidenced by the serial killer case examples reported through NIJ’s programs — and the knowledge that criminals tend to repeat their crimes — many unresolved homicides are likely to lead to persons responsible for multiple killings. Thus, solving one case is likely to solve multiple cases. For example, one detective seeking to identify the remaining victims of John Wayne Gacy resolved 11 other missing persons cases in the process, several of which were homicides.[33]

Investigative Practices

One NIJ-funded study examined effective investigation practices for cold cases. Researchers found that cold cases were usually opened because new witnesses came forward or DNA tests were conducted on retained physical evidence (some of which was collected before the most current DNA technologies became available).[34]

They also found that the amount of resources dedicated to cold case investigations, particularly the level of funding, significantly affected the cold case clearance rate.[35] More recent cases were more likely to be solved than older ones. Also, if the victim was found inside his or her own home, chances of solvability increased. The justification for opening the cold case investigation mattered as well: Cold cases were most likely to be cleared if the cases were initiated by investigators through new evidentiary leads.[36] In sexual assault cases, victim cooperation was found to be related to a successful conviction rate.[37]

Science and Technology

Advancements in science and technology have helped solve cases that were once unsolvable. DNA — an unknown evidence source in the 1980s — can now be analyzed with a fraction of the sample size needed merely five years ago. Meanwhile, upgraded computer search algorithms[38] are realizing connections between friction ridge impressions[39] that were not identifiable during previous searches.

See “NamUs-FBI Fingerprint Collaboration Partnership”

Tapping into technology can propel a stalled cold case investigation forward. For example, innovations in DNA databases’ search capabilities are connecting crimes to other crimes and to those who committed the crimes.[40] The Golden State Killer alone was connected to 12 homicides, more than 50 sexual assaults, and hundreds of incidents of burglaries, peeping, stalking, and prowling[41] through DNA database connections.

In conventional practice, DNA database searching consists of seeking an exact match at 20 DNA loci between evidence and samples in the CODIS database from other crime scenes or convicted persons or arrestees. Some jurisdictions are finding success through less precise (lower stringency) searching, giving them the ability to find individuals related to the suspect. This can be done by simply noting partial matches, or through specific software algorithms designed to identify family members (i.e., familial searching).[42]

ICF International, in an NIJ-funded study, found that 11 states allowed familial DNA searching and that 24 states and Puerto Rico disclosed DNA hits based on partial matches. The labs that engaged in familial DNA searching were starting to see arrests leading to convictions, albeit in a small number of cases. ICF also found that key stakeholders who championed the use of familial searching along with establishing clear policies led to greater use of this technique.[43] As use of this technique becomes more familiar, and as more cases are cleared through partial-match and familial searching, it is foreseeable that this practice may expand or lead to other innovative DNA searching methods.

In addition, information is more accessible today. Investigators can connect suspects to crimes using the vast amount of information available through the internet and electronic records, as illustrated by recent news stories of cold cases that were resolved through genealogy databases.

See “DNA and Cold Case Investigations”

Auditing the Evidence

Cold case investigators and laboratories across the country have realized that auditing cold cases may help clear them. As with any process, there can be gaps and oversights, and many investigators have learned that these may exist in evidence databases.

For example, capturing DNA from criminals, according to the locality’s defined offense criteria, is a common practice and has been occurring for decades, but many have managed to avoid it. Investigators routinely submit evidence to labs, hoping that their unknown DNA profile matches an entry from a known person in CODIS. This is possible if the suspect was previously convicted (and, in some states, arrested). But what if the suspect was arrested or convicted prior to DNA collection laws? What if the suspect was committed for mental observation and the DNA collection process was circumvented? What if the suspect died without DNA being collected? Investigators may identify a suspect in a cold case merely by auditing the evidence, case files, and associated databases and recognizing a gap or oversight.[44]

Cold cases also have the benefit of time. Situations change, relationships change, and barriers — such as the previously uncooperative spouse who is now an ex-spouse, willing to share his or her knowledge — can help resolve cold cases. Scientific processes also evolve with time. Having the ability to patiently and thoroughly investigate a cold case, rather than acting reactively or responding only to recent situations, affords investigators the ability to research and apply all available tools for resolving today’s cold cases, preventing future crimes, and potentially catching a serial killer. Agencies need only apply resources to capitalize on these assets.

There has never been a better time to address cold cases. With the advantages of research, technology, and time, agencies can greatly benefit from addressing the cold case crisis in the United States and, as a consequence, serial killings can be identified, solved, and prevented.

For More Information

- Read NIJ’s National Best Practices for Implementing and Sustaining a Cold Case Investigation Unit.

- Learn more about NamUs.

- Watch a video on the impact of NIJ’s Solving Cold Cases with DNA program.

- Read the related NIJ Journal article “Cold Cases: Resources for Agencies, Resolution for Families.”

- Watch a video on the importance and impact of cold case units.

About This Article

This article was published in the NIJ Journal Issue Number 282.

Sidebar: The Costs and Benefits of Cold Cases

In numerous ways, investigating and resolving cold cases benefits law enforcement agencies, the communities they serve, and society as a whole. First and foremost is the safety of the community. When those who have committed crimes are incarcerated, the community is spared their crimes and residents feel safer. Safety is both real and perceived. With respect to the latter, unresolved crimes can lead to mental health and financial costs — for example, businesses might suffer when customers avoid particular times and locations because they are afraid. Those who commit serial offenses contribute to these fears — their crimes are compounded by notoriety, and with each unsolved case there is a growing sense of prevalent danger in the community.

Secondly, and no less important, is the sense of justice that survivors feel when those who committed the crime are apprehended.[45] Survivors often feel that law enforcement has given up on them and that the lives of their loved ones are no longer a priority.[47] Law enforcement has a moral obligation to fulfill its mission; because cold cases capture public interest, resolving them inspires public confidence in law enforcement.

In addition to promoting safety and justice, preventing future crime and clearing active cases result in enormous financial savings. Although very difficult to calculate, the costs of crime are generally believed to be extremely high, ranging from $690 billion to $3.41 trillion annually.[47] Many variables determine the costs of crime: crime prevention efforts, direct consequences of crimes such as medical and funeral costs for victims, crime responses, and investigations, as well as the costs of moving suspects through the legal system and incarcerating them. Even harder to quantify are the intangible costs to victims and the community. Fear and post-traumatic responses may be somewhat quantifiable if psychological help and physical security enhancements could be calculated; however, the emotional costs can never be measured.

Sidebar: NIJ Programs Help Support Cold Case Investigations

The Postconviction DNA Testing Assistance program (Postconviction DNA Testing to Exonerate the Innocent) is designed to review evidence in cases where DNA analysis may substantiate claims of a potential wrongful conviction.[48] Grantees have reported that, in some cases, not only were those convicted not responsible, but also the true culprits appeared to be serial killers. For example, in North Carolina, Leon Brown and Henry Lee McCollum were convicted for the murder of Sabrina Buie, but subsequent DNA testing exonerated them and revealed that Roscoe Artis, a convicted rapist and killer, was Buie’s likely killer.[49]

NIJ also tracks the outcomes of criminal justice programs, including those related to cold cases and individuals who repeat violent offenses, and supports behavioral and social science research through its Social Science Research on Forensic Science (SSRFS) portfolio. SSRFS was born out of a need to understand both the potential and the limits of forensic science in bringing those committing offenses to justice. Its diverse topics have included studying the effectiveness of an innovative forensic method,[50] understanding the perception of forensics in the courtroom,[51] and assessing the benefits of expanding the use of DNA testing beyond serious violent crime.[52] SSRFS’s research has identified effective practices for the apprehension of serious violent criminals,[53] which include pursuing cold cases, employing alternative DNA searching technologies, and investigating property crimes. This program gives agencies an understanding of the full spectrum of investigative opportunities open to them through the use of forensic methods.

Sidebar: NamUs-FBI Fingerprint Collaboration Partnership

In 2017, the FBI and the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) entered into a partnership in which the friction ridge impression records for missing and unidentified persons that NamUs collected were searched against the FBI’s Next Generation biometric database. As of September 30, 2019, 259 identifications of unidentified persons have been made through this partnership. Most notably, 28 of those identified are confirmed homicide victims.

A significant number of the unidentified human remains in NamUs have a cause of death that is undetermined or unlisted. The probability that at least some of these NamUs cases are homicide victims means that the partnership with the FBI is likely to turn up many additional homicide leads. Recognizing a homicide and identifying a victim is a major first step in resolving cold cases and identifying serial killers.

Sidebar: DNA and Cold Case Investigations

Emerging DNA analysis applications that may assist in cold case investigations include DNA phenotyping, forensic genetic genealogy (FGG), and DNA mixture interpretation. DNA phenotyping is the use of DNA information to predict the physical features of a person (their phenotype), such as eye, skin, and hair color. A sketch of a person’s appearance can be generated by combining the information from several phenotypically important genes. NIJ research has included projects such as identifying genetic markers in DNA that contribute to skin pigmentation.[53]

FGG is a process whereby DNA profiles are used in conjunction with genealogy investigations to identify relatives of an unknown donor of a DNA sample. It should be noted that the DNA profiles used in law enforcement databases differ from the DNA profiles obtained through the commercial DNA genealogy sites that FGG relies on. The U.S. Department of Justice published an interim policy on the use of FGG in September 2019 to ensure that law enforcement practices continue to protect the rights of people who use public genealogy resources while also incorporating FGG to identify potential investigative leads.[55] The use of FGG led to the identification of the Golden State Killer.

Because violent crimes involve the interaction of two or more people, multiple DNA profiles may be mixed together in evidence. Using probabilistic software in DNA analyses has allowed analysts to separate or interpret individual DNA profiles from such mixtures where previous analyses provided inconclusive results. In addition, NIJ-funded research is applying machine learning to DNA mixture interpretation, improving results by incorporating data from previous analyses.[56]

NIJ continues to fund research and development for advancing new DNA technologies. Many of these technologies, however, are still evolving and may not provide solutions in the near future. But in cold cases, where there may be little evidence and few to no investigative leads, new technologies may, in time, provide just enough information to propel a cold case investigation toward its next steps.

Appendix A: Serial Killer Cold Cases Assisted by NIJ Funding

Grantee: City of Boston (MA)

Awards: 2009-DN-BX-K253; 2012-DN-BX-K005

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1962-1964

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age Possible Victims

- Anna Slesers, 56

- Mary Mullen, 85

- Nina Nichols, 68

- Helen Blake, 65

- Ida Irga, 75

- Jane Sullivan, 65

- Sophie Clark, 21

- Patricia Bissette (pregnant), 23

- Mary Brown, 68 Beverly Samans, 23

- Evelyn Corbin, 58

- Joann Graff, 23

- Mary Sullivan, 19

NIJ’s Involvement in Resolution: Before his death in 1973, Albert DeSalvo had recanted his confession of killing Mary Sullivan in the 1960s, although investigators still believed he killed her. With the help of two NIJ grants, the Boston Police Department was able to use Y-STR DNA analysis and familial DNA interpretation methods to link Albert DeSalvo’s nephew to evidence in the Sullivan case. DeSalvo was exhumed to confirm the match and solve the murder of Mary Sullivan.

Grantee: City of Los Angeles (CA)

Award: 2009-DN-BX-K007

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1985-2007; possibly inactive 1988-2002

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age Possible Victims:

- Debra Jackson, 29

- Henrietta Wright, 35

- Barbara Ware, 23

- Bernita Sparks, 25

- Mary Lowe, 26

- Lachrica Jefferson, 22

- Alicia Alexander, 18

- Princess Berthomieux, 15

- Valerie McCorvey, 35

- Janecia Peters, 25

Could be up to 25 female homicide victims

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: DNA had previously linked the murders of several Black women from the 1980s, and in 2010, the City of Los Angeles received permission to do a familial DNA search of their DNA database to provide more investigative leads. They found a match and, after investigation, pursued the father of the person whose profile provided the familial DNA match. NIJ funding enabled the Los Angeles Police Department’s crime laboratory to analyze discarded pizza crusts and utensils from a pizza restaurant to confirm a DNA match between Lonnie Franklin Jr. and several of the victims. Franklin was convicted for the murder of nine women and one girl in 2016.

Grantee: Ventura County (CA); Orange County (CA) Sheriff, Coroner Division; Sacramento (CA) District Attorney; Placer County (CA)

Award(s): 2005-DN-BX-K003; 2008-DN-BX-K311; 2010-DN-BX-K014; 2012-DN-BX-K009; 2014-DN-BX-K062; 2005-DN-BX-K016; 2008-DN-BX-K136; 2005-DN-BX-K030; 2008-DN-BX-K147; 2008-DN-BX-K207

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1974-1986

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Janelle Cruz, 18

- Keith Harrington, 24

- Patti Harrington, 27

- Greg Sanchez, 27

- Cheri Domingo, 35

- Robert Offerman, 44

- Debra Manning, 35

- Katie Maggiore, 20

- Brian Maggiore, 21

- Lyman Smith, 43

- Charlene Smith, 33

- Manuela Witthuhn, 28

- Claude Snelling, 45

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: NIJ funded five Solving Cold Cases with DNA awards to Ventura County from 2005 to 2014, two awards to the Orange County Sheriff’s Coroner Division, two to the Sacramento District Attorney’s Office, and one to Placer County. With NIJ funding, DNA from sexual assault and homicide victims was linked to one person who was known by several monikers throughout the state. In 2018, investigators used a genealogy website to probe for leads in capturing this prolific rapist and killer, and zeroed in on Joseph James DeAngelo. He was arrested on April 24, 2018, after police confirmed the DNA match through a piece of trash discarded by DeAngelo that had a biological sample on it.

Grantee: University of North Texas Health Science Center

Award(s): 2010-DN-BX-K206; 2015-DN-BX-K070

Program: Using DNA Technology to Identify the Missing

Years Active: 1972-1978

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Victim No. 5, 22-32

- Victim No. 10, 17-21

- Victim No. 13, 17-21

- Victim No. 14 (once thought to be Michael Marino)

- Victim No. 21, 21-27

- Victim No. 26, 22-30

- Victim No. 28, 14-18

- Timothy McCoy, 15

- John Butkovich, 18

- Darrel Samson, 19

- Samuel Stapleton, 14

- Randall Reffett, 15

- Michael Bonnin, 17

- William Carroll, 16

- Jimmy Haakenson, 16

- Rick Johnston, 17

- William Bundy, 19

- Kenneth Parker, 16

- Gregory Godzik, 17

- John Szyc, 19

- Jon Prestidge, 20

- Matthew Bowman, 18

- Robert Gilroy, 18

- John Mowery, 19

- Russell Nelson, 21 or 22

- Robert Winch, 18

- Tommy Boling, 20

- David Talsma, 20

- William Kindred, 19

- Timothy O’Rourke, 20

- Frank Landingin, 19

- James Mazzara, 20

- Robert Piest, 15

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: After recovering 33 bodies from John Wayne Gacy’s property and the Des Plaines River, eight of the victims remained unidentified in 2011. The Cook County (IL) Sheriff’s Office reached out to the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNT-HSC) for help in identifying these victims. Through a Using DNA Technology to Identify the Missing grant, UNT-HSC confirmed the identity of victim No. 19 as William Bundy through DNA analysis of family reference samples. In 2017, another grant to UNT-HSC funded the DNA analysis of family reference samples to identify victim No. 24 as Jimmy Haakenson.

Grantee: Harris County (TX)

Award: 2014-DN-BX-K072

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1970s and 1980s

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Adam Walsh, 6

- George Sonnenberg, 64

- Ada Johnson, 19

Unknown how many victims

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: Ottis Toole partnered with Henry Lee Lucas and together they confessed to an alleged crime spree that, at times in the confession, reached 3,000 victims in several different states, with Toole giving corroborating stories to Lucas’ confessions. Toole himself was convicted of six counts of murder, including the infamous murder of Adam Walsh. No one is sure how many victims the partners had together or separately, as they both allegedly killed independently before and after they were together. The Harris County Crime Laboratory analyzed DNA evidence through a Solving Cold Cases with DNA award on two cases thought to be linked to these murderers, although no conclusive link was able to be made.

Grantee: Harris County (TX)

Award(s): 2014-DN-BX-K072

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1970s and 1980s

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Viola Lucas (his mother)

- Frieda “Becky” Powell

- Kate Rich

- “Cheryl” Jane Doe, 17

Unknown how many victims

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: Henry Lee Lucas partnered with Ottis Toole and confessed to an alleged crime spree that, at times in the confession, reached 3,000 victims. Many crimes he confessed to were proved later to be committed by someone else, and most confessions were so implausible that police did not believe him. Lucas was convicted of 11 murders in total, although no one truly knows how many victims he had. The Harris County Crime Laboratory analyzed DNA evidence through a Solving Cold Cases with DNA award on two cases thought to be linked to these murderers, although no conclusive link was able to be made.

Grantee: King County (WA) Sheriff’s Office; University of North Texas Health Science Center; The Bode Technology Group, Inc.

Award(s): 2004-RG-CX-K011; 2010-DN-BX-K206; 2010-DN-BX-K257

Crime Laboratory Improvement Program; Using DNA Technology to Identify the Missing

Years Active: 1982-1998, possibly through 2001

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Wendy Coffield, 16

- Debra Bonner, 22

- Marcia Chapman, 31

- Cynthia Hinds, 17

- Opal Mills, 16

- Debra Estes, 15

- Carol Christensen, 21

- Gisele Lovvorn, 19

- Terry Milligan, 16

- Alma Smith, 18

- Delores Williams, 17

- Gail Mathews, 23

- Sandra Gabbert, 17

- Carrie Rois, 15

- Mary Meehan (pregnant), 18

- Andrea Childers, 19

- Constance Naon, 19

- Kelly Ware, 22

- Linda Rule, 16

- Denise Bush, 23

- Shirley Sherrill, 18

- Shawnda Summers, 16

- “B10” Jane Doe, 12-18

- Cheryl Wims, 18

- Colleen Brockman, 15

- Kimi-Kai Pitsor, 16

- Sandra Denise Major, 20

- “B17” Jane Doe, 14-18

- Marie Malvar, 18

- Martina Authorlee, 18

- Debbie Abernathy, 26

- Mary Bello, 25

- Pammy Avent, 16

- Roberta Hayes, 21

- Marta Reeves, 36

- Yvonne “Shelly” Antosh, 19

- Tina Thompson, 22

- April Buttram, 17

- Maureen Feeney, 19

- Tracy Winston, 19

- Delise Plager, 22

- Kim Nelson, 21

- Lisa Yates, 19

- Mary West, 16

- Cindy Smith, 17

- Patricia Barczak, 19

- Patricia Yellowrobe, 38

- “B20” Jane Doe, 13-24

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: The King County Sheriff used DNA analysis funded with a 2004 NIJ Crime Laboratory Improvement Program grant to link Gary Ridgway to four of the known “Green River Killer” homicide victims. Once Ridgway’s interrogation started, he became talkative and confessed to murdering 71 women. Ridgway pleaded guilty to 48 charges of aggravated first-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison for each of the 48 victims in 2003. Authorities have found 49 sets of remains, though four victims remained unidentified until 2012. Through NIJ funding, the University of North Texas Health Science Center was able to confirm the identity of Sandra Major, once only known as “Jane Doe B16.”

Grantee: Napa County (CA) Sheriff’s Department

Award(s): 2010-DN-BX-K018

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1963-1970

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Betty Lou Jensen, 16

- David Faraday, 17

- Darlene Ferrin, 22

- Michael Mageau, 19, survived

- Cecelia Shepard, 22

- Bryan Hartnell, 22, survived

- Paul Stine, 29

- Donna Lass, 25

Claimed a total of 37 victims

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: This unsolved case remains open, with investigators from Napa County continuing to send evidence for DNA analysis and review case files with funding started from a Solving Cold Cases with DNA grant in 2010. Investigators also sent latent prints from some of the cases for analysis. Although the murderer known only as the Zodiac Killer claimed 37 victims, investigators agree on and can confirm five homicide victims and two attempted homicide victims.

Grantee: Denver (CO) Police Department, Crime Laboratory Bureau

Award(s): 2007-MU-CX-K223; 2009-DN-BX-K012

Programs: Denver Integrated Cold Case DNA Unit Demonstration Model; Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1978-1988

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Emma Jenefor, 25

- Peggy Cuff, 20

- Joyce Ramey, 23

- Pamela Montgomery, 35

- Tammy Sue Woodrum, 17

- Juanita Lovato, 19

- Diane Montoya Mancera, 25

- Rhonda Fisher, 30

- Carolyn Buchanan, 25

- Faye Johnson, 22

- Jeanette Baca, 17

- Zabra Mason, 19

- Karolyn Walker, 18

- Juanita Mitchell, 25

- Pamela Morgan, 17

- Norma Jean Halford, 21

- Cynthia Boyd, 19

Total could be as high as 24

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: The Denver Police Department connected four homicide cases (Jenefor, Cuff, Ramey, and Montgomery) to deceased convicted killer Vincent Groves, using funding from two different NIJ grants. The Denver Crime Laboratory analyzed DNA evidence and connected the four victims to Groves, who had been previously convicted for the murders of Woodrum, Lovato, and Mancera. Groves died in prison in 1996, but now, four more homicide cases have been closed.

Chester Todd

Grantee: Denver (CO) Police Department, Crime Laboratory Bureau

Award(s): 2009-DN-BX-K012

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: Unknown

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Sherri Majors, 27

- Male, in 1967

Unknown number of women

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: Chester Todd was arrested in Las Vegas (NV) in 2010 but died in prison, awaiting his trial for the murder of Sherri Majors. An NIJ grant funded the DNA analysis that identified the blood found in Todd’s truck as Majors’ blood. The FBI and task forces in several states identified a pattern of homicides and rapes of prostitutes at truck stops across the country and named Chester Todd as the main suspect eight years after the murder of Majors.

Grantee: Marion County (FL); County of Riverside (CA)

Award(s): 2010-DN-BX-K011; 2012-DN-BX-K028

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1980-2013

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- David Bedolla, 23 (CA)

- Sylvester Ayon, 30 (CA)

- G.G., 17 (CA), survived

- Raul Gonzalez, 22 (CA)

- Domingo Perez, 29 (CA)

- Santiago Perez, 56 (CA)

- Javier Huerta, 20 (FL)

- Gustavo Olivares-Rivas, 28 (FL)

- Jose Alvarado, 25 (CA)

- Juan Bautista Moreno, 52 (CA)

- Joaquin Barragan, 45 (CA)

- Gonzalo Urquieta, 54 (CA)

- Jose Ruiz, 32 (AL)

As many as 20 other victims in AL, AR, CO, FL, GA, IA, ID, MO, OK, OR, and WA

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: After being caught and confessing to a homicide in Alabama, Jose Manuel Martinez shocked the chief investigator for the Lawrence County (AL) Sheriff’s Office by confessing that he had killed over 30 people in Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Missouri, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Washington. He confessed to being a contract killer for drug cartels and for anyone who would hire him, although some homicides were personal, such as the murder of a man in Alabama and three men in Riverside County (CA). Through NIJ funds, Riverside County submitted evidence for analysis from a triple homicide believed to be attributed to Martinez after he wrote a letter to that county’s Sheriff’s Office, confessing to killing three men in 1978 who had murdered his sister that same year. Also through NIJ funds, the Marion County (FL) Sheriff’s Office reviewed two homicide cases that were unsolved until Martinez began confessing in 2013. Martinez was handed 10 consecutive life sentences in California in 2015 for nine murders and one attempted murder, 50 years in prison in Alabama in 2014 for one murder, and went to trial in June 2019 for a double murder in Florida.

Grantee: North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts

Award(s): 2012-DY-BX-K001

Program: Postconviction DNA Testing Assistance Program

Years Active: 1980-1983

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Sabrina Buie, 11

- Joann Brockman, 16

- Bernice Moss, 30

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: In 2015, half-brothers Leon Brown and Henry Lee McCollum were exonerated and pardoned on the rape and murder of Sabrina Buie. They had served nearly 31 years in prison for that crime before a request from McCollum’s lawyer started a more thorough investigation into the crime as both Brown and McCollum maintained their innocence. NIJ funding allowed DNA analysis of a cigarette butt found near the victim’s body; the profile that was generated did not match either Brown or McCollum. Instead, it matched Roscoe Artis, a man who had been convicted of assaults on six different women and was suspected in the Bernice Moss case — a case with details nearly identical to Buie’s case. Artis is already serving a life sentence in prison for the rape and murder of Joann Brockman, a crime committed just weeks after Buie’s murder.

Grantee: Colorado Attorney General

Award(s): 2009-DN-BX-K242

Postconviction DNA Testing Assistance Program

Years Active: 1990-1996

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Jacie Taylor, 19

- Susan Doll, 39

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: In 2012, Robert Dewey was exonerated after serving 16 years in prison for the murder of Jacie Taylor. Dewey was convicted in 1996 and, after losing his appeals, his attorney approached the Colorado Attorney General’s Office for help. NIJ funding allowed postconviction investigators to test fingernail scrapings and other pieces of evidence to obtain a single male profile that matched Douglas Thames Jr. Thames was already in prison for the rape and murder of Susan Doll, a crime committed five years before Taylor’s murder, which went unsolved until 1995. Both Dewey and Thames were convicted in 1996. In 2015, Thames was convicted for Taylor’s murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Grantee: Boise State University

Award(s): 2016-DY-BX-0006

Program: Postconviction Testing of DNA Evidence to Exonerate the Innocent

Years Active: Unknown

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Donna Meagher, 34

- Gregory Giannonatti, 57

- Beverly Giannonatti, 79

Unknown how many victims in CA, FL, NV, and WA

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: In 2018, Paul Jenkins and Freddie Joe Lawrence were exonerated after serving 23 years in prison for the murder of Donna Meagher, who had been beaten to death with a hammer in conjunction with a robbery in 1994. In 2017, NIJ funds allowed DNA testing on several pieces of evidence. The profiles generated matched David Wayne Nelson, who had been convicted of a double murder in 2015 in which both victims had been beaten with a hammer. Nelson bragged about being a hit man and killing people in California, Florida, Nevada, and Washington state. It is unknown how many people Nelson has actually killed.

Grantee: City of Phoenix (AZ) Police Department

Award(s): 2014-DN-BX-K070

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1992-??

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Melanie Bernas, 17

- Angela Brosso, 22

- Brandy Myers, 13

- Shannon Aumock, 16

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: When Melanie Bernas and Angela Brosso, two young women, were found murdered in the Arizona Canal in Phoenix in the early 1990s, evidence on their bodies contained an unknown DNA profile. The Phoenix Police Department requested the assistance of a forensic genealogist from California, and her analysis of the DNA profile led to a last name: Miller. In 2014, NIJ funding allowed DNA testing to confirm a link between the “Miller” DNA from the victims and a biological sample surreptitiously collected from Bryan Miller. After further investigation, police arrested Miller for the murders of Bernas and Brosso. Miller is also suspected in the disappearance of 13-year-old Brandy Myers but has not been charged yet. He is currently awaiting trial for the murders of Bernas and Brosso.

Grantee: City of Los Angeles (CA) Police Department

Award(s): 2007-DN-BX-K026

Program: Solving Cold Cases with DNA

Years Active: 1972-1989

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Ethel Sokoloff, 68

- Elizabeth McKeown, 67

- Cora Perry, 79

- Maybelle Hudson, 80

- Miriam McKinley, 65

- Evalyn Bunner, 56

- Adrian Askew, 56

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: In the 1970s and 1980s, two waves of sexual assaults and homicides plagued the Los Angeles and Claremont areas. All of the cases remained unsolved until 2009, when the Los Angeles Police Department used NIJ funding to analyze the evidence and collected DNA samples. John Floyd Thomas Jr. was linked to the murders of two women after his DNA was collected during the investigation of the Grim Sleeper cases and as part of a push to collect DNA from persons registered for having committed a sex offense. After being linked to five more murders, Thomas was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. He remains a suspect in 10 to 15 more homicides as well as up to 30 sexual assaults.

Grantee: City of New York (NY) Office of Chief Medical Examiner

Award(s): 2010-DN-BX-K131

Program: Using DNA Technology to Identify the Missing

Years Active: 1993-1994

Confirmed Homicide Victims, Age:

- Colleen McNamee, 20

- Rita Tangredi, 31

- Sandra Costilla, 28

NIJ's Involvement in Resolution: Eleven sets of human remains were recovered along a beach in Long Island, NY. Several of the victims were dismembered and only partially recovered. With NIJ funding, New York City’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner helped determine the identities of six victims. It also matched two sets of remains recovered from separate locations to one victim, who remains unidentified. The medical examiner’s office also obtained a partial familial DNA match between DNA samples collected from two victims found on Long Island and the brother of John Bittrolff. Bittrolff was confirmed as an exact match to the DNA from the victims and was subsequently convicted. His case was the first homicide conviction in New York based on a partial DNA match — although it still remains unclear whether Bittrolff is the “Long Island Killer” or only one of perhaps multiple killers who disposed of their victims in that area.