Home | Glossary | Resources | Help | Contact Us | Course Map

Archival Notice

This is an archive page that is no longer being updated. It may contain outdated information and links may no longer function as originally intended.

Alternate Materials

Brass is the most commonly used material in the production of the modern cartridge case. Mild steel cartridge cases and bullet jackets are manufactured outside of the United States. Another alternative material is aluminum alloy, which is used to produce centerfire cartridge cases. Other materials, such as plastic, have been tried but have not been widely accepted.

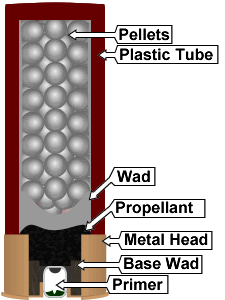

Shotshell

Shotshells operate at low pressures, roughly half that produced by the .22 Long Rifle cartridge. Although some military shotshell cartridges were made of brass, by the turn of the twentieth century, the hybrid case was the standard for commercial shotgun cartridges. At that time, the cases consisted of a wound paper body, a horsehair (or other natural fiber) base wad, and a small brass jacket that formed the rim and held the base wad in place.

The paper tube (still used in some modern target shotshells) was made on a long metal mandrel with an outside diameter matching the inside diameter of a finished shotshell. Wide sheets of thin paper were passed through melted wax and wrapped on the rotating mandrel. Dozens of layers of wax were applied to make the case wall the correct thickness. The paper-feed cut the paper and sealed the cut end to the tube. After cooling, the tube was stiff and relatively water resistant due to the wax. The wax also served as the adhesive that prevented the layers from separating. The resulting tube was long enough to be cut into three or more shotshells.

In the 1960s, plastic began to replace paper and fiber components in the sidewalls of shotshell cases. Heat and air pressure was used to produce strong, thin-wall tubes from preformed thermoplastic cylinders. This was adopted by shotshell makers to improve the paper tube case; it was not waterproof and when wet, would swell. Plastic tubes could be made in any length.

Eventually, this experimentation led to the one-piece shotshell case. Rather than cutting tubes to length and adding separate base wads, conventional plastic injection molding methods were used to create a case with an integral base wad. The cases were not truly one piece they still retained the separate metal head cover. Although the plastic cases were functional without metal heads, the heads made the shells more durable for multiple cycles through shotguns.

One-piece molding added a case feature not possible with paper or the initial plastic process the skived or tapered case mouth. Tapering the walls of a plastic case reduces the force needed to form the crimp that will seal the shell. In spite of the acceptance of the one-piece shotshell case, today's market contains examples of every tube type, including paper.

Shotshell Wads

Wads are used to prevent the mixing of propellants and pellets in a shotshell. The wad forms a critical gas seal at firing to keep the expanding gases behind the shot charge. Wads also act as spacers, setting the correct volume for the propellant and shot charges and cushioning the pellets to reduce deformation. For years, shotshell wads were simple disks of fiber, felt, or cardboard cut to fit the inside of a shotshell case. A hard, nonflammable wad, sometimes called a nitro wad, was placed over the powder.

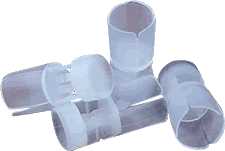

In the 1960s, shotshell engineers realized that modern plastics could improve shotshell performance. Initially, plastic shot wrappers (simple flat sheets of polyethylene) were used to protect lead pellets from scuffing on the bore as they passed. Conventional fiber wads continued to be used after plastic shot wrappers appeared. Eventually, the hard-to-load plastic sheet material was replaced with an easily installed shot cup that was closed at the bottom.

The first plastic shotshells still used a metal rim assembly and a separate fiber base wad. The base wad provides support for the primer and controls powder space. Some fiber wads were plastic coated to prevent swelling. In some cases, the entire base wad was made of plastic and inserted in the tube.

It did not take long to realize that a contoured over-powder wad molded from plastic was more effective for obturation than the flat cardboard nitro wads. Molded with skirts to bear and seal against the barrel wall, these wads soon became commonplace, even when fiber wads were still used for spacing and cushioning. The evolution of wad design integrated the skirted base, pellet cushioning, and the pellet wrapper into one molded unit.

Additional Online Courses

- What Every First Responding Officer Should Know About DNA Evidence

- Collecting DNA Evidence at Property Crime Scenes

- DNA – A Prosecutor’s Practice Notebook

- Crime Scene and DNA Basics

- Laboratory Safety Programs

- DNA Amplification

- Population Genetics and Statistics

- Non-STR DNA Markers: SNPs, Y-STRs, LCN and mtDNA

- Firearms Examiner Training

- Forensic DNA Education for Law Enforcement Decisionmakers

- What Every Investigator and Evidence Technician Should Know About DNA Evidence

- Principles of Forensic DNA for Officers of the Court

- Law 101: Legal Guide for the Forensic Expert

- Laboratory Orientation and Testing of Body Fluids and Tissues

- DNA Extraction and Quantitation

- STR Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Communication Skills, Report Writing, and Courtroom Testimony

- Español for Law Enforcement

- Amplified DNA Product Separation for Forensic Analysts