Home | Glossary | Resources | Help | Contact Us | Course Map

Archival Notice

This is an archive page that is no longer being updated. It may contain outdated information and links may no longer function as originally intended.

Bolt Actions

Another basic action design that ultimately provided military applications was the turn-bolt action. Known today as bolt action, it copied the principle of the locking bolt on a door. The door bolt has a rod with a handle attached. When the handle is in one position, the bolt is free to move back and forth. In another position, the handle falls into a slot to keep the bolt locked forward. The firearm action works nearly identically. Early bolt-action firearms were locked for firing when the root of the bolt handle was closed against the receiver. Rotating the bolt handle 90 degrees unlocked it, and pulling it back made the chamber available.

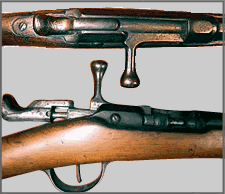

The French Chassepot Model 1866 is an excellent example of an early military bolt action firearm. It displays the rudimentary bolt action with its primitive bolt handle locking the action.

Although modern bolt actions are much improved, the basic design remains the same. The rod-shaped bolt is compact, producing a narrow side-to-side profile for the rifle. The shape of the bolt equally distributes thrust forces; this was improved upon in later designs. Most importantly, the stroking action used to manipulate the bolt and the extra room under the receiver and barrel set the stage for repeating bolt-action arms.

As cartridges grew more powerful, the simple locking action of the bolt handle root became less effective. The relative distance between the bolt handle and the cartridge, as well as the stress of firing, caused the bolt body to compress between the cartridge and the lock surface. For a low-power cartridge, this is not a concern. However, for a high-power cartridge, if the compression is too great, some cartridge support is lost, creating the risk of gas leaking into the shooters face.

The necessity of stronger locking systems led to repositioning the locking surfaces so that the bolt handle root became a backup rather than a primary locking point. Protruding lugs were placed on the bolt body and rotated into corresponding recesses when the action was closed for firing. The placement and the number of lugs varied from one design to another. The most effective designs placed at least two generous lugs just behind the bolt face (breech face), the surface against which the cartridge rests when the action is locked. In the best examples, the bearing surfaces of the lugs are approximately in the plane of the cartridge base.

Two basic designs emerged in military turn-bolt rifles: the Austrian Mannlicher and the German Mauser. Derived from the Chassepot, these bolt-action arms influenced the development of most military and sporting rifles.

Mannlicher Action

To this day, the Mannlicher retains a feature of the Chassepotthe split receiver bridge. The bolt handle lies in the ejection port when the bolt is closed and must pass through the split in the bridge to open the action. The split effectively guides the bolt handle and smoothes the feel of the action. However, the split reduces the usefulness of the bridge to accommodate extra features, such as special sights and loading aids. The ammunition for Mannlicher military actions has to be packed in retaining clips; these remain in the rifle after loading and become part of the feed system.

Mauser Action

Early Mausers also started with the split bridge, but with a better safety mechanism than contemporary Mannlichers. By 1889, Mauser had adopted a solid bridge placed in front of the bolt handle. The solid bridge provided a support point for stripper clips to facilitate faster loading. The clip is placed in a rest in the bridge, and the shooter strips the cartridge out of the clip into the rifles integral box magazine; the empty clip falls away when the bolt is closed. By 1893, Mauser had abandoned the protruding Mannlicher-style magazine in favor of an internal one that staggered the cartridges side to side for a better fit. Milled from steel, the new Mauser magazine was durable. Stamped sheet metal clips were not required in critical feed operations once the rifle was loaded.

The pinnacle of the military bolt-action rifle was the Mauser Model 1898. The Model 1898 had two forward locking lugs, one large nonbearing safety lug at the rear of the bolt body, and an additional projection behind the bolt handle as an auxiliary safety lug. The bolt body was vented to channel gas from a ruptured cartridge away from the shooters face. The feed mechanism controlled the movement of the cartridge from magazine to chamber. A three-position safety mechanism (acting directly on the firing pin) allowed the rifle to be safely loaded and unloaded. The firing pin automatically moved out of engagement with the firing-pin release mechanism.

The Model 1898 Mauser became the basis of the U.S. Model 1903 Springfield rifle. These designs influenced most modern bolt-action sporting rifles and are among the strongest actions built.

Additional Online Courses

- What Every First Responding Officer Should Know About DNA Evidence

- Collecting DNA Evidence at Property Crime Scenes

- DNA – A Prosecutor’s Practice Notebook

- Crime Scene and DNA Basics

- Laboratory Safety Programs

- DNA Amplification

- Population Genetics and Statistics

- Non-STR DNA Markers: SNPs, Y-STRs, LCN and mtDNA

- Firearms Examiner Training

- Forensic DNA Education for Law Enforcement Decisionmakers

- What Every Investigator and Evidence Technician Should Know About DNA Evidence

- Principles of Forensic DNA for Officers of the Court

- Law 101: Legal Guide for the Forensic Expert

- Laboratory Orientation and Testing of Body Fluids and Tissues

- DNA Extraction and Quantitation

- STR Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Communication Skills, Report Writing, and Courtroom Testimony

- Español for Law Enforcement

- Amplified DNA Product Separation for Forensic Analysts