In a perfect world, a push of a button would connect all juvenile court judges and authorized staff to relevant local child welfare files for each young person summoned before the court. The imperfect reality is that in many American juvenile court systems, there is no button, no data linkage — no way to readily retrieve the often-instructive personal histories found in child welfare data.

Many jurisdictions lack even a culture of collaboration between child welfare services and juvenile justice, an interagency nexus needed to identify and attend to the unique, complex needs of so-called dual system youth — a vulnerable, high-risk population.

It falls to judges to be the catalysts of connectivity between juvenile justice and child welfare services, research[1] and experience have shown. “Judicial leadership is the single most important factor for successfully implementing the dual system crossover youth model, without question,” said Richard N. White, magistrate of the Mahoning County (OH) juvenile court. He added, “It is driven from the bench.”[2]

For leadership to make inroads against a nationwide challenge, however, scientifically sound, data-driven systems are needed to illuminate the population of dual system youth and their distinctive needs.

Dual system youth are a subset of “crossover youth” — juveniles who have been both victims of maltreatment and engaged in delinquent acts. The dual system youth population consists of crossover youth who have entered, at some point, both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems (see exhibit 1).

The National Institute of Justice recognizes that having a dual system youth’s child welfare history at hand could help juvenile courts figure out what remedies would, or would not, be suitable in particular cases. Interactive data linkages could help drive collaborative case management by child welfare and justice agencies. They could help inform and refine best practices for a jurisdiction’s work with vulnerable youth. In addition, they could help researchers identify youth trajectories, assess interventions, quantify trends, and fuel future reforms. Finding out what works is also essential to refining public policy.

Without functional data linkages between the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, child welfare agencies and researchers are often hard-pressed to learn what becomes of child clients if and when they enter the juvenile justice system. That connective knowledge can be crucial to discovering which child welfare interventions correlate with the best outcomes for the individual down the line, and which interventions may be less promising, or even ineffective, in the long run.

The data disconnect between child welfare and juvenile justice agencies that are dealing with the same young people has hidden a long-suspected truth about American youth who enter the juvenile justice system: Most youth who come to the attention of the juvenile justice system due to their engagement in delinquent behavior also have experience as victims served by the child welfare system.

The Dual System Youth Design Study, led by investigators at California State University Los Angeles, closely examined three jurisdictions with well-developed juvenile justice/child welfare data linkages.[3] This recent research established that half of the young people entering those court systems had past or current engagement with child welfare, or would become engaged with child welfare after a first contact with juvenile justice. The study also concluded that, throughout the nation today, half or more of youth entering the juvenile justice system might well be dual system youth with histories of child welfare intervention.

It should be noted that the inverse is not the case: The majority of all child welfare clients never enter the juvenile justice system. But the dual system youth subpopulation tends to have longer histories in child welfare, more out-of-home placements, and higher recidivism than youth who experience the child welfare or juvenile justice system alone.[4] African Americans have a higher probability of dual system youth status, as do females. Overall, youth with protracted child welfare histories, including multiple placements outside of the home, tend to penetrate the juvenile justice system more deeply.

For policymakers and practitioners, better solutions to the distinctive needs of dual system youth are likely to require robust, multipronged strategies. These include:

- Broad adoption of integrated data systems between child welfare and juvenile justice agencies.

- Further development and dissemination of best practices for dual system youth, enabled by the adoption of a rubric, or measuring methodology, that breaks down progress into specific milestones.

- Collaboration between juvenile justice, child welfare, and other service agencies, along with judicial leadership.

- Policies, starting at the federal level, focused on preventing maltreatment, preventing delinquency among young people who experience maltreatment, and supporting integration of practices for dual system youth. Public policy reforms should support interventions targeting, in particular, those dual system youth with longer histories of child welfare involvement, with multiple out-of-home placements of long duration.

A Brief History of Research and Policy Development

The full magnitude of the child maltreatment/juvenile delinquency connection has eluded researchers for decades, but the importance of that connection has long been evident. In 1984, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention convened 31 experts spanning the fields of sociology, criminology, psychology, law, medicine, social work, juvenile justice, philanthropy, child abuse, and child advocacy to address the relationship of child abuse to delinquency. As noted in the symposium’s report, “Child abuse and delinquency are not separate problems. They are intertwined in known and unknown ways. Isolated statistics and separate studies have existed for some time, and common sense leads one to postulate a strong link.”[5]

The symposium experts determined that retrospective studies of youth involved in the juvenile justice system consistently have found that they experienced maltreatment at rates much higher than the general population. The report authors noted the shortcomings of existing research, including inconsistencies in definitions, lack of comparison groups, and reliance on either self-report or official records rather than both. They recommended further research and development focused on child abuse prevention and coordinated intervention for youth involved in the juvenile justice system who experienced child abuse. The research, prevention, and intervention issues raised in this seminal 1984 symposium permeate our current research, policy, and practice.

The Unique Challenges Posed by Dual System Youth

Juvenile court staff note that dual system youth pose a special challenge for juvenile courts, in part because many young people in that segment have suffered double adversity — a pronounced lack of family support coupled with serious maltreatment (i.e., abuse or neglect). Magistrate White of Mahoning County said that, in his experience, those entering juvenile courts with a strong family support system stand a much better chance of a positive outcome and limited justice system exposure.

“When I’m on the bench and I have a child who is in front of me for the first time — let’s say it’s a property crime — and you have family support that you see in front of you, the chances of success are overwhelming,” said White, who is deeply involved in implementing policy and practice for dual system youth. “This is a first occurrence, and you have the family to carry out any of the sanctions and any of the treatments and services that you put in place. In many cases, that may well be the last time you see the child.”

In cases where the child lacks family support, and in fact has suffered maltreatment at home that triggers time in the child welfare system, the juvenile court dynamic is far different — provided the court knows of the maltreatment history. “It is a devastating situation for a child where there is no family support, and then in addition there is abuse or neglect by members of that family,” White said. “I don’t know that a child could be in a more difficult situation.”

“When you’ve identified a child as a dual system child, then you know there is a whole other series of issues that must be addressed, and you can’t simply stay focused on this delinquency piece,” he added.[6]

Data Linkage: A Key to Understanding

For juvenile justice to holistically address issues confronting the dual system youth population, child welfare and juvenile justice data must be linked, both to identify individual needs and address them through proven remedial protocols.

The Dual System Youth Design Study team defined the key role that data linkages must play in improved systemic help for the dual system youth population. Given that social science already suggests that more than half of the juvenile justice population has or will have child welfare involvement, those linkages will be key to integrating programs between child welfare and juvenile justice agencies. They will also enable identification and support of those dual system youth subgroups on the most difficult developmental pathways.

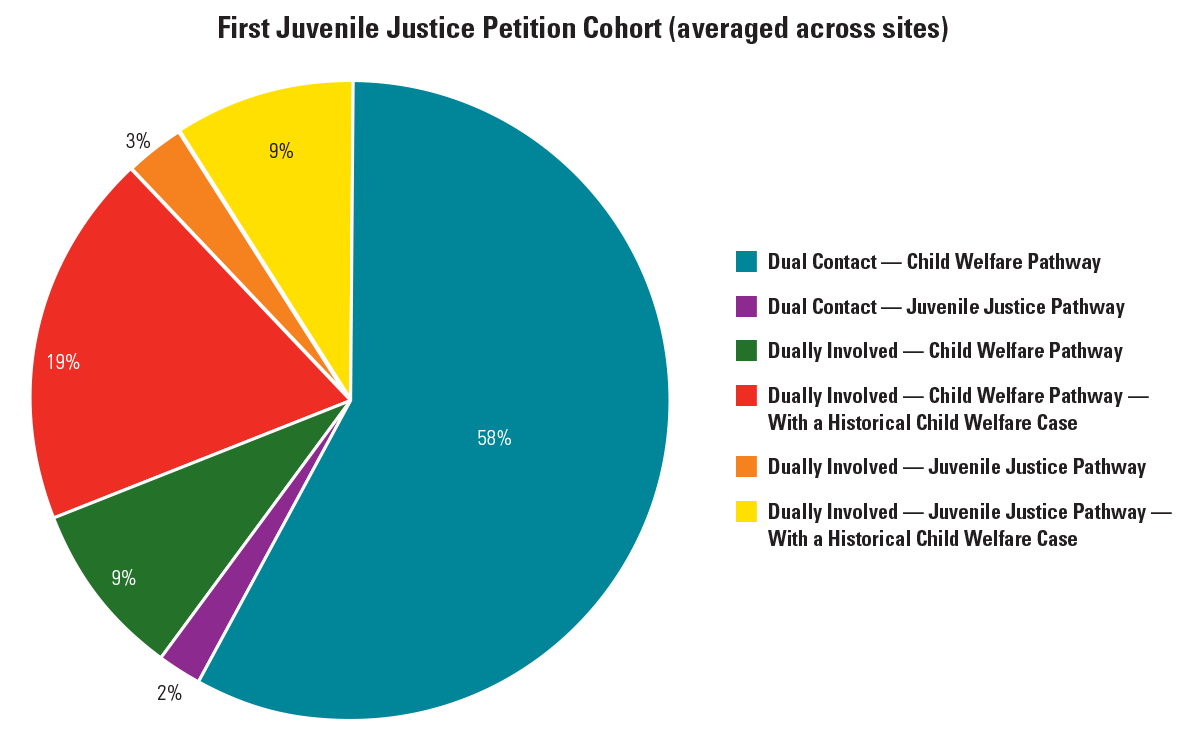

A central element of the study was a deep analytical dive into administratively linked child welfare/juvenile justice data from three jurisdictions — New York City, Cook County (Chicago), and Cuyahoga County (Cleveland). The researchers examined all youth whose first juvenile justice petition was filed in 2013 or 2014 in New York City, and between 2010 and 2014 in Cook County and Cuyahoga County. That analysis yielded the incidence rates for dual system youth shown in exhibit 2.

| Jurisdiction | Number of Youth in Study Cohort |

Prevalence of Dual System Youth Among First Juvenile Justice Petition Cohort |

|---|---|---|

|

New York City, NY |

1,272 |

70.3% |

|

Cuyahoga County, OH |

11,441 |

68.5% |

|

Cook County, IL |

14,170 |

44.8% |

The study confirmed and strengthened confidence in prior research findings that dual system youth represent a massive challenge for juvenile courts and child service agencies throughout the nation. As the study’s report concluded, “Research demonstrates that at least half of juvenile justice youth have touched the child welfare system at some point in their lives.”[7]

The Dual System Youth Design Study team theorized six pathways into system involvement typically taken by dual system youth, then used linked administrative data from the three jurisdictions to illuminate which of those pathways were placing youth at greater risk for negative outcomes, such as higher rates of juvenile detention and recidivism.

For definitional purposes, youth who had contact with both child welfare and juvenile justice, but not at the same time, were labeled “dual contact” youth. Those who had contact with both systems at the same time were deemed “dually involved” youth. Another factor informing a dual system youth’s pathway through the systems was whether that young person had first contacted child welfare or first contacted juvenile justice. An additional consideration for those youth who were dually involved was whether they had a separate historical — that is, preexisting — contact with the child welfare system. For example, the pathway marked by dual concurrent involvement with child welfare and juvenile justice, where the first contact was with the child welfare system, and with an earlier, separate contact with child welfare, was labelled “Dually Involved Youth Child Welfare Pathway with a Historical Child Welfare Case.”

The Dual System Youth Design Study team initially identified the following discrete pathways (see exhibit 3):

- Dual Contact — Child Welfare Pathway

- Dual Contact — Juvenile Justice Pathway

- Dually Involved — Child Welfare Pathway

- Dually Involved — Child Welfare Pathway — With a Historical Child Welfare Case

- Dually Involved — Juvenile Justice Pathway

- Dually Involved — Juvenile Justice Pathway — With a Historical Child Welfare Case

Applying data from deep statistical dives done at the three sites, the researchers refined those pathways. With data indicating the majority of dual system youth do not touch both systems at the same time, the researchers emphasized the need for systems to review a youth’s complete history, rather than simply the present. The researchers isolated two dually involved youth subgroups as especially high risk, regardless of whether their child welfare involvement was historical or concurrent with their juvenile justice contact: (1) those with a long duration in child welfare and (2) those with a higher incidence of out-of-home placement as part of their child welfare exposure. Those experiences tended to put dual system youth most at risk for negative outcomes, the study reported.[8] Generally, all dually involved youth — those whose contact with child welfare and juvenile justice overlapped — “had earlier, longer, and deeper contact with the child welfare system.”[9]

By enabling identification of the dual system youth population, and of those dual system youth segments at greatest risk for delinquency or further abuse, administrative data linkages can help drive collaboration tailored to individual needs and risks. “Without question, the administrative data findings reinforce the need for cross-system collaboration and the implementation of integrated systems practice across the child welfare and juvenile justice system,” the study report said.[10]

Using a Best Practices Rubric

If collaboration is vital to improved dual system youth services, developing best practices in each jurisdiction is vital to effective collaboration. Giving child welfare and other support agencies a greater voice in shaping the outcomes of juvenile justice cases can best support youth who are experiencing maltreatment or a lack of family support.

The second part of the Dual System Youth Design Study used case studies from 41 jurisdictions that are implementing the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform’s Crossover Youth Practice Model[11] to identify best practices for guiding collaboration regarding dual system youth. The study identified several practices most commonly implemented and prioritized across the sites, including early identification of dual involvement, improved information sharing across child welfare and juvenile justice systems, and coordinated case supervision.

The study team used its Crossover Youth Practice Model data analysis to create a “best practices rubric,” a protocol for measuring each agency’s progress across 11 performance areas, or “domains.” The domains were:

- Interagency collaboration

- Judicial leadership

- Information sharing

- Data collection

- Training

- Identification of dual system youth

- Assessment process

- Case planning and management

- Permanency and transition plan

- Placement plan

- Service provision and tracking

For each domain, the rubric identified progress milestones toward best practice fulfillment on a continuum from “practice not in place” to “highly developed” practice. The team said that jurisdictions that are most fully evolved across the 11 domains will arguably have the most positive impacts on dual system youth.[12] Developing a rubric that helps agencies closely gauge their progress toward best practices is “one critical step” toward preventing young people from touching both systems, or at least reducing their involvement with juvenile justice, the research team reported.[13]

The team also stressed that preventing maltreatment, and preventing delinquency for those who experience maltreatment, are essential for reducing dual system contact and involvement.[14] For dual system youth, cross-system collaboration is essential for mitigating even deeper involvement with the juvenile justice system.[15] Early intervention against abuse and neglect reduces the likelihood of delinquency.[16]

Teamwork and Leadership

The tension inherent in the twofold mission of juvenile justice has long been evident, as the juvenile justice system serves both to address juvenile delinquency in order to protect community safety and to provide intervention services to promote positive adolescent development. A 1969 Supreme Court decision quoted a juvenile court jurist describing juvenile justice as “an uneasy partnership of law and social work.”[17]

That tension is reflected in the difficulty of forging collaborative, interagency solutions featuring tested protocols and team-building. According to White, the Mahoning County juvenile court magistrate and head of that county’s multiagency dual system youth team, part of the problem is the false assumption of many juvenile justice staff throughout the country that they already understand the issues of dual system youth who come before the court. “In many of the jurisdictions we have worked with, when you first present the dual system model, the answer you get is, ‘We’re already doing it.’ I cannot tell you the number of times I have heard that in all good faith. It’s just that without training and education, they don’t realize how involved these cases can be, and how you have to have an orderly, organized plan to deal with them,” said White, who also took part in a national initiative to promote and install crossover youth reforms.[18]

When a dual system juvenile is identified, White explained, the court “can’t simply stay focused on the delinquency piece. You must put the team together, to address all aspects of what’s going on in this child’s and the family’s lives.” The organized collaborative approach, he added, “allows us to intervene early and swiftly and stop further penetration into the delinquency system.”[19]

Mahoning County was one of 41 sites that generated data for the Dual System Youth Design Study. Those sites had adopted the Crossover Youth Practice Model devised by the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform.

The study’s report emphasized the critical leadership role judges must play for interagency collaboration to succeed for dual system youth. The study team singled out Mahoning County as an exemplar of judicial leadership in implementing the Crossover Youth Practice Model. The Mahoning County juvenile court judge, Theresa Dellick, was a force for change as she assembled, engaged, and arranged training of multiagency stakeholders for a dual system youth team, according to White. “She is the person who absolutely insisted that we implement the Crossover Youth Practice Model in 2012,” White recalled. “She was the visionary without any doubt, or we would not have done it. She put me in charge of the implementation of it, and since then we have just embraced it, run with it — and I don’t know how we ever survived without it.”[20]

In Mahoning County, White said, the Crossover Youth Practice Model team operation continues to run smoothly, eight years after implementation and without grant support or other special funding.

Policy Needs: Advancing Collaboration and Prevention for Maltreatment

Meaningful national progress in addressing the needs of this substantial at-risk population will require additional support for the development of integrated system practices, the Dual System Youth Design Study team concluded. Emphasis must be placed on codifying best practices in law and policy, with reforms across the federal, state, and local levels:[21]

- Committing resources and incentivizing community-based efforts to prevent maltreatment and delinquency before children, youth, and their families touch the child welfare or juvenile justice system.

- When system involvement is necessary, mandating better and more consistent identification of dual system youth, and evaluating integrated systems approaches to improving their outcomes.

- Funding community-based alternatives to removing children and youth from their families.

- Funding better data systems, particularly for juvenile justice systems.

- Mandating training at state and local levels on integrated system practices, and evaluating those practices.

- Identifying dual system youth as early as possible and providing comprehensive services — an essential building block for improving dual system youth practices. The key to reducing dual system contact and involvement is prevention, the study team emphasized. Preventing maltreatment and interrupting persistent maltreatment should be a priority because early intervention can reduce the likelihood of delinquency, according to the study report. Ultimately, the research team concluded, “well-developed policies depend on recognizing dual system youth as a critical target population rather than a marginal one.”[22]

Conclusion

In sum, dual system youth merit timely, systematic identification; collaborative service delivery across the child welfare and juvenile justice systems; meaningful assessment of service delivery; and evaluation of the impact of integrated service delivery on key life outcomes.

An underlying prerequisite for both identification of and service delivery to those who meet the definition of dual system youth is developing the capacity for functional, linked administrative data. The study report recommends conducting an in-depth national assessment of dual system youth data capacity to advance both research and practice perspectives. Such an assessment could inform sound investment in the development of linked administrative data capacity.

The compelling need to advance technology and systems in support of dual system youth is informed by recognition of the profound human need informing these cases. In every case, a young individual faces serious, potentially life-altering challenges meriting the full attention of both juvenile justice and child welfare professionals. As observed by the principal investigator of the Dual System Youth Design Study, Denise Herz: “With deeper and more precise knowledge of pathways, we can reframe the narrative around dual system youth and fundamentally change the cultures of both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems.”[23]

For More Information

Watch a Research for the Real World seminar on the Dual System Youth Design Study.

About This Article

This article was published as part of NIJ Journal issue number 283. This article discusses the following award:

Evolution of Research Insights Into Dual System Youth

Over the decades, researchers have progressed in their examination of life course events punctuated by the involvement of children and youth across both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. In the Rochester Youth Development Study, researchers examined the history of child maltreatment and the intervention of child protective services among a general population sample. This longitudinal study provided strong evidence that youth who experienced maltreatment during childhood displayed at least a 25% increase in risk for problems during adolescence, including serious and violent delinquency, drug use, low academic achievement, symptoms of mental illness, and teen pregnancy.[24]

In the Dual System Youth Design Study, the researchers reviewed the literature,[25] noting that most studies are either prospective and begin with children served by the child welfare system, or retrospective and look back in time for maltreatment histories among youth entering the juvenile justice system. Although relatively few child welfare clients end up in the juvenile justice system, a much higher percentage of all youth involved in the juvenile justice system have a history in the child welfare system. When contrasted with youth involved only in the juvenile justice system, dual system youth exhibit higher levels of mental illness, substance abuse, educational challenges (such as truancy, suspensions, and lower academic performance), and recidivism. As dual system youth age, they are also more likely to experience adverse outcomes, including homelessness, incarceration, and unemployment as young adults.

Recognizing the negative consequences associated with dual system involvement, researchers and practitioners have emphasized the need to reframe policy and practice to increase the (1) efficacy of delinquency prevention among the child welfare population, (2) systematic identification of dual system youth, (3) collaborative case management across child welfare and juvenile justice, and (4) provision of trauma-informed services. Collaborative efforts in more than 100 jurisdictions in the United States[26] have been guided and supported through training and technical assistance delivered by the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform[27] and the Robert F. Kennedy Children’s Action Corps National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice.[28]

With respect to integrated systems work, the final report of the design study observed a significant gap in the literature: “To date, very little evaluation research has been published that examines youth outcomes associated with cross-system collaboration and practice change to support dual system youth. In part, this is due to the difficulty of designing a well-controlled, rigorous evaluation within and across these complex systems.”[29]

As noted by the researchers involved in the Dual System Youth Design Study, the current literature has other key limitations, including a lack of comprehensive national studies or estimates of incidence, inconsistencies across studies in definitions of key terms, and a lack of distinctions in the types of trajectories of dual system contact. One major objective achieved by the design study team was the development of a sound methodological approach to generating national estimates of the incidence of dual system youth, incorporating greater clarity in definitions and trajectories. The research team laid out a study design plan in the final technical report built on a consensus that only a robust national sampling of data linkages between child welfare and juvenile justice agencies can deliver a statistically sound estimate of the total population of dual system youth. At present, implementing this design would be challenging because all states and jurisdictions have not sufficiently developed the capacity to effectively link these administrative data records. The Dual System Youth Design Study provides a roadmap for building data linkage capacity nationwide in order to develop national estimates and to inform the future agenda for both research and practice.