Numerous cities across the country struggle with high rates of violent crime. In many of our most dangerous communities, social ills like poverty, unemployment, and lack of opportunity lead to tragic circumstances in which systemic violence can easily take root.

To combat this problem, the U.S. Department of Justice launched the Violence Reduction Network (VRN) in 2014.[1] VRN unites local law enforcement and criminal justice leaders with federal resources to tackle violent crime. Cities are chosen to participate in the program on an annual basis, with the goal of improving the level of knowledge, communication, collaboration, and tactics involved in addressing violent crime.

The National Institute of Justice funded an evaluation of the early phases of the VRN (April through December 2015) including a review of planning, implementation process, and progress for the original five 2014 VRN sites, but not an assessment of program’s impact as it is too soon to determine the impact on crime reduction. The evaluation and subsequent assessment report were produced by Edward Connors, J.D. and Gary Cordner, Ph.D.

About the Violence Reduction Network

DOJ’s Office of Justice Programs launched VRN on September 29, 2014. Led by OJP’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), VRN consults with U. S. Attorneys and DOJ law enforcement partners to select VRN sites annually based on rigorous selection criteria; principally, violent crime rates that are well above the national average, jurisdictions from diverse geographic regions with distinct characteristics, and readiness to participate in this collaborative initiative.

VRN has its foundation in Maryland’s Safe Streets initiative that focused on core groups of persons who commit the majority of violent crimes and drug offenses.[2] Additionally, VRN is similar in structure to the Community Oriented Policing Services Office's collaborative reform program, which also helps police departments keep up with DOJ policy and practices. The core principles of community policing are partnerships, problem-solving, and organizational transformation — principles also observed in VRN.

The initiative seeks to enable local law enforcement agencies to work with the federal partners to identify problems and implement law enforcement strategies to produce meaningful results for the community. BJA provides no direct grant funding through VRN, but resources are provided to local agencies through existing training and technical assistance (TTA) programs.

VRN delivers its strategic, intensive TTA in an “all-hands” approach, leveraging existing DOJ resources to provide free, site-specific, customized training to increase local agencies’ capabilities to address challenges related to violence reduction in the most affected communities (BJA, 2017). Federal agencies that collaborate to provide TTA under VRN include the Office of Justice Programs, Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Marshals Service, U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, Executive Office for United States Attorneys, Office on Violence against Women, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

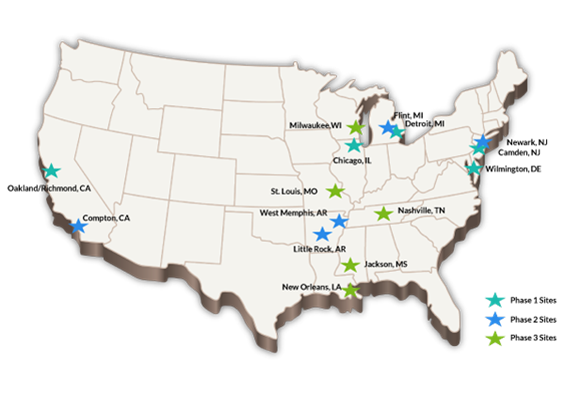

Since 2014, VRN has expanded from the five original partner sites addressed in the NIJ funded evaluation of the early phases of this program to fifteen cities in nine states (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

| FY 2014 | FY 2015 | FY 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| Camden, NJ | Compton, CA | Milwaukee, WI |

| Chicago, IL | Flint, MI | New Orleans, LA |

| Detroit, MI | Little Rock, AR | St. Louis, MO |

| Oakland/Richmond, CA | Newark, NJ | Jackson, MS |

| Wilmington, DE | West Memphis, AR | Nashville, TN |

Figure 1: 2014-2016 VRN Partner Sites[3]

Each participating site has an assigned strategic site liaison, who is a law enforcement professional that coordinates with the local U.S. Attorney to assist sites in identifying and obtaining available DOJ resources. VRN also provides sites with tools to enhance information sharing, including best practices shared through the network’s website and clearinghouse, webinars, and peer-to-peer exchanges. An annual VRN Summit provides participating sites with an opportunity to take part in collaborative working sessions with federal leadership. The Summit focuses on analyzing site-specific violence challenges and presents the variety of available DOJ resources.

Assessment Methods

In 2015, NIJ funded a process assessment to critically examine program activities, characteristics, and outcomes. Edward Connors, J.D., and Gary Cordner, Ph.D., conducted the assessment, including review and analysis of activities at the federal level among participating DOJ agencies and at the local level in each of the 2014 VRN cities.

Assessment methods were mainly qualitative in nature and took place over a span of nine months (April-December, 2015). Strategies used to collect process-level information included interviews, observations, site visits, and document reviews. The assessment team observed and interacted with VRN program management, staff, consultants, and site representatives. The team also conducted observation-based analyses of past and present police agency management, organizational behavior, and operations to account for temporal changes in these areas.

Assessment Findings

In their assessment report, Connors and Cordner (2016) summarized the following key VRN objectives:

- Re-engineer federal-to-federal and federal-to-local relationships and implement a resources delivery model with data-driven strategies to target sites’ most urgent violent crime needs (focusing on homicides and shootings).

- Collectively assess site-related needs and specific drivers of violent crime, and collaboratively develop sustainable strategies.

- Improve knowledge of what works through information sharing and network building with an aim of creating a community of practice, and demonstrate changes in local policing in line with best practices.

The assessment team found that VRN delivers on its project objectives. The scope of delivery is site specific, as expected, based on the various levels of crime and each site’s unique system characteristics. The program successfully supports police agencies needs and fills gaps in service by providing support to each jurisdiction’s evolving and existing strategies to combat violent crime.

Evaluators determined that VRN has made headway in improving federal-to-federal and federal-to-local relationships with regards to violent crime prevention and reduction strategies. It is also evident from the assessment that DOJ partner agencies contribute to VRN and that federal law enforcement agencies in VRN are building coalitions within VRN sites. These federal agencies assume the role of “champions” that coordinate support but do not direct it (Connors & Cordner, 2016).

Sites have also enhanced relationships and communication with DOJ law enforcement agencies and improved understanding of the range of infrastructure (i.e., training, crime analysis, staffing resources, technology, and programs) required to develop and maintain the capabilities to effectively combat violent crime. Although some of the sites already had a good relationship with most of the DOJ law enforcement agencies, participation in VRN has improved relationships and led to more timely and responsive support to sites’ needs. The assessment team also found that DOJ partner agencies are collaborating efficiently and effectively in their effort to support and assist the sites, and local law enforcement recognizes value in the federal assistance.

VRN implements data-driven strategies to identify and target each site’s most urgent violent crime needs. The initiative then makes available a large, provisional pool of resources that sites can access when demand spikes. Resources include expedited access to subject matter experts and customized TTA. The program’s support for crime data helps sites develop ongoing performance measures that focus on violent crime reduction.

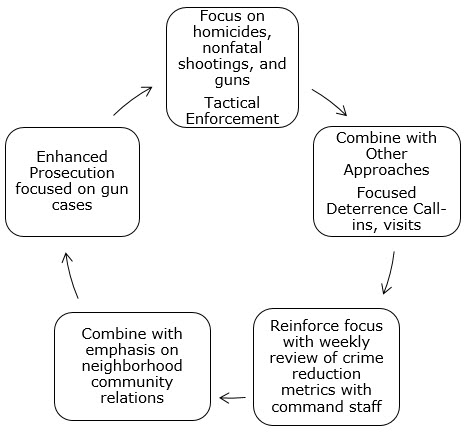

VRN does not rely on every site following a particular model or set of program elements. Rather, it is characterized by flexibility, allowing local sites to identify their needs and select appropriate TTA and other resources. However, evaluators identified five core VRN focus areas, which are outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Illustration of VRN Core Focus Areas Modeled after Connors & Cordner[4]

VRN coordinates support from DOJ law enforcement agencies, while using strategic site liaison and analysts to assess the local drivers of violent crime and the need for sustainable strategies to combat crime. The assessment found that the strategic site liaisons were former chief executives, with the exception of one former deputy chief of a major city police department. The evaluation team found that the liaisons succeeded in establishing trust with local agencies, delivering on program commitments, focusing on active support versus critiques, and using appropriate collaboration and facilitation skills.

Researchers concluded that the information sharing and network building component of VRN has improved knowledge and encouraged development of a community of best practices, resulting in structural and operational changes of the participating agencies. The program has provided opportunities for local partners to acquire grants from federal agencies, foundations, and others. It is also evident that VRN's TTA led to the implementation of evidence-based practices aiming at combating violent crime. Among the many TTA offerings, VRN sites unanimously agree that they benefited most from peer visits, which enabled them to learn best practices from other agencies.

Challenges to Implementation

Although VRN has been successfully implemented, the program does face challenges moving forward. One key lesson that VRN management learned in working with large agencies was that future VRN applications should be restricted to one or two police precincts or districts (i.e., high violent crime locations) and not the entire city. Such approach could be more efficient not only because implementing change on a large-scale is often time-consuming and might require numerous attempts, but also makes it easier to promote community-wide engagement in violent crime reduction strategies at a smaller jurisdiction level. In addition, there is a potential for VRN sites to become overwhelmed with the amount of data, technology, and related training that the program provides. Expanding VRN’s scope may overwhelm program management if no additional support is provided.

The evaluation also found that some strategic site liaisons worked offsite, resulting in limited face-to-face contact with participating agencies. Some sites lacked an experienced technical writer to consult when addressing the challenges of writing grant proposals.

VRN was in its formative stages during the evaluation, and the program’s continuation and expansion will present additional challenges. The expansion may require more resources to operate effectively and efficiently. Sites also need to ensure police legitimacy and fairness, increase community engagement, and consider community environmental factors.

Yet another VRN challenge is that the program does not assist sites with documenting practices or lessons learned. According to the evaluation, some sites noted that PowerPoint presentations are less effective than written guidance or booklet in helping them to, for example, learn and use new software.

The Way Forward

Despite these challenges, the assessment found that VRN has been successfully implemented across sites. The evaluation identified several core factors to the program that will enable continued successful implementation moving forward.

First, DOJ leaders support VRN’s implementation and evolution by providing immediate feedback and positive support on program successes. Management prioritizes OJP/BJA resources for the participating sites and facilitates communication with DOJ leadership.

Second, the decision to create a co-director and partnership structure (one from federal law enforcement and one from program/grant agencies) has enabled federal law enforcement to have an equal share in VRN oversight and decision-making. Such structure also helps DOJ law enforcement agencies at their respective headquarters and promotes collaboration and communication among the agencies, which is reflected in the decision to prioritize the allocation of resources. A VRN hallmark is cooperation among DOJ law enforcement and program and grant-making agencies at the local VRN site level.

Third, strategic site liaisons are a key aspect of VRN’s success. Selecting the right liaisons is vital. They are practitioners with necessary knowledge of the local site, experience with evidence-based violence reduction practices, familiarity with local-state-federal law enforcement relationships and operations, and an in-depth understanding of organizational innovation, police cultures, data systems, and research. They also bring collaboration, communication, facilitation, listening, and leadership skills to the program.

Fourth, the success of the VRN program depends on the analyst assigned to each local site. Analysts provide logistic and other support to strategic site liaisons, help plan and execute on-site TTA, coordinate meetings, and produce event summaries. One site stated that they rely as much on the analysts as the liaison to make the program work.

Fifth, central to VRN’s success is extensive communication. During the assessment period, VRN management maintained regular contact with site activities through weekly planning calls of all key managers and other actors, bi-weekly calls with strategic site liaisons and analysts, and monthly calls with strategic site liaisons, analysts, and federal “champions.” The calls, which mostly focused on TTAs, webinars, or meeting logistics, enabled key players to stay current with VRN developments and were used for immediate problem-solving and for setting future goals and objectives.

Sixth, TTA provider capabilities and competencies played a vital role in VRN’s success. OJP/BJA selected two contractors to help manage the VRN program: the Institute for Intergovernmental Research (IIR) and Center for Naval Analyses Corporation (CNA). IIR managed the information exchange support (e.g., newsletters, website, and webinars), peer visits, summits, and more, and CNA managed the strategic site liaisons and analysts, and most of the TTA. Both are highly experienced in managing OJP grant programs and work well together, largely due to a clear delineation of tasks and assignments, close communication and efficient meeting facilitation, and commitment to serve the client and the project.

It is too early to determine whether VRN had a positive impact on crime reduction, but the evaluation shows that the program is driving change in local police agencies through improved TTA, resource delivery, and collaboration. Importantly, VRN is viewed positively by participating local law enforcement agencies. It is also evident that VRN enhances participating sites by delivering a broad spectrum of resources and support, which leads to positive change at the community level. It is, however, imperative for participating sites to develop sustainability plans to ensure the continued effective implementation of crime reduction strategies.

About the Author

Basia E. Lopez (Combs), MPA, CCIA, is a Social Science Analyst in the Crime and Crime Prevention Division, Office of Research and Evaluation, at the National Institute of Justice.