Advances in the technology for processing and analyzing DNA evidence -- plus maintenance and expansion of the National DNA database -- have brought about a profound change to the criminal justice system.

The broad use of DNA technology in forensic laboratories, starting in the early 2000s, gave us a powerful tool that has not only improved the investigation of sexual assault and other serious crimes but has also helped solve cold cases, identify the missing, and exonerate hundreds of innocent people who were convicted of crimes they did not commit.

At the same time, concern has been growing about the nation's response to sexual assault. Concerns range from the large numbers of sexual assault kits in police storage that have never been tested, to the high number of assaults that were never reported, to the response to sexual assault on campuses.

Advances in science are making it possible for forensic labs to identify trace amounts of DNA from evidence. Science is also helping us identify more effective methods to support victims. Studies in neuroscience, for example, are showing how trauma may affect a victim's ability to remember and explain details of an assault. Social science research is providing evidence-based guidance on collecting evidence to improve investigation and prosecution.

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ), the scientific research arm of the U.S. Department of Justice, supports a range of studies related to sexual assault, especially research related to the processing and testing of sexual assault kits. NIJ has worked with a number of cities -- Los Angeles, New Orleans, Detroit, Houston, and others â in leading the way toward change.

The first step is knowing what works. Our scientists are building evidence-based knowledge about how to develop priorities for testing unsubmitted sexual assault kits, following up on hits from the DNA database, and notifying victims of new developments in their cases.

-- Nancy Rodriguez, Director, National Institute of Justice

Sexual Assault Kits

What Is a Sexual Assault Kit and How Is It Used?

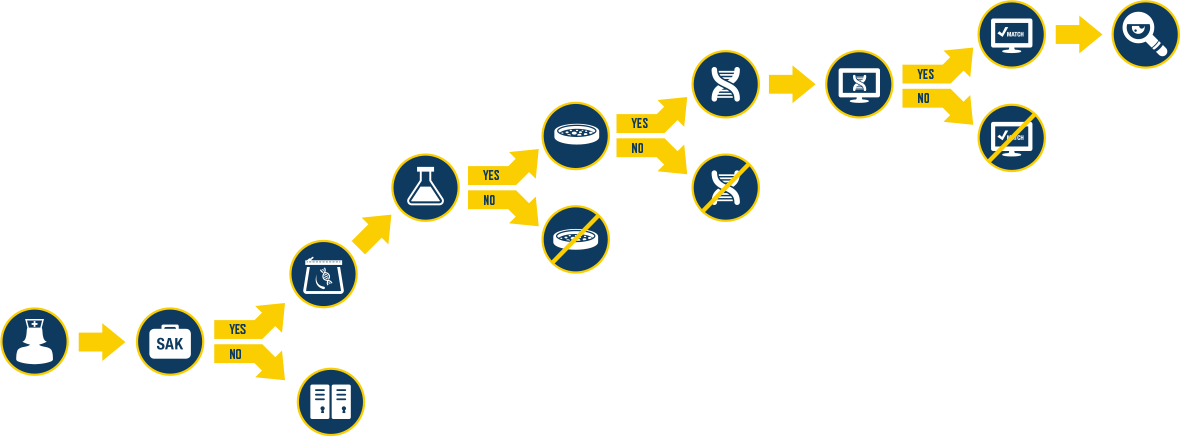

A sexual assault kit (SAK) is a collection of evidence gathered from the victim by a medical professional, often a specially trained Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE). The type of evidence collected depends on what occurred during the assault. The contents of a kit vary by jurisdiction, but generally include swabs, test tubes, microscopic slides, and evidence collection envelopes for hairs and fibers.

The sexual assault kit evidence may contribute to investigations, prosecutions and exonerations in sexual assault cases.

Testing a SAK is one part of the investigative process, but testing does not always result in a new investigative lead. For example, the suspect may already be known, or the evidence in the kit does not contain any or enough biological evidence to yield a DNA profile.

The medical examination is highly invasive and can last several hours. The victim is swabbed for any biological evidence that may contain the perpetratorâs DNA (e.g., skin, saliva, semen). The examiner also photographs any bruising or other injuries, collects the victimâs clothing, and provides the victim with medicine to prevent infection or pregnancy, if the victim chooses. Evidence collected from the victim goes into the sexual assault kit. The SAK and other crime scene evidence, such as bedding, can be tested in an effort to identify the perpetrator.

Typically, after the examination is completed, the SAK is transferred to an authorized law enforcement agency to be logged into evidence. Protocols vary among jurisdictions regarding whether and when the SAK is sent to the lab for testing. Identifying reasons why some SAKs, historically, were not submitted for testing and researching new ways to improve the processing of sexual assault kits have been goals of recent NIJ efforts, such as the action research projects with Detroit and Houston.

Action Research

Two Cities Use a Multidisciplinary Approach

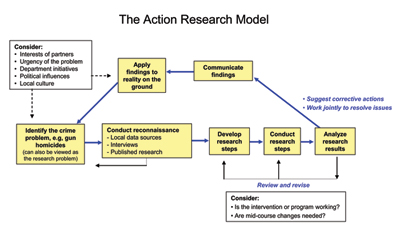

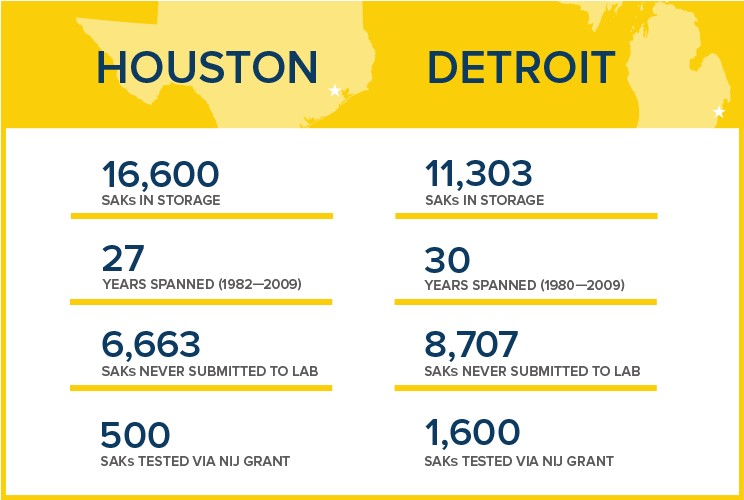

In 2011, NIJ awarded grants to the Houston, TX, Police Department and the Wayne County (Detroit, MI) Prosecutorâs Office to conduct action research projects that would (a) investigate the large numbers of SAKs that had not been submitted to a crime laboratory, and (b) use scientific methods to determine how best to proceed.

The multidisciplinary Houston Action Research Project team, which included representatives

from law enforcement, medical, crime lab, advocacy, and legal organizations.

The two jurisdictions formed multidisciplinary teams of researchers and practitioners.

The practitioners came from several organizations and included police officers, sexual assault forensic examiners, crime lab analysts, prosecutors, and victim advocates.

The researchers and practitioners worked collaboratively to:

- Determine how many SAKs had not been submitted for testing.

- Identify underlying factors that caused the problem.

- Develop a plan for testing unsubmitted SAKs, including prioritization.

- Create and evaluate a victim notification protocol.

The projects were undertaken to support the cities of Houston and Detroit and to build a knowledge base that could help other jurisdictions respond to sexual assault crimes.

Action research builds long-term partnerships among agencies and researchers and also builds research capacities within the agencies involved in the projects.

â Bill Wells, Research Partner, Sam Houston State University

A Team Effort

A Team Effort and a Systemic Response

To better understand how large numbers of unsubmitted kits accumulated, and to prevent the problem from recurring, both cities found that regular communication, collaboration and cooperation among all the stakeholders were essential.

The multidisciplinary teams shared in making decisions and recommendations on how to handle unsubmitted kits and improve sexual assault responses in current cases.

Practitioners from law enforcement, the district attorneyâs office, forensic science, medical and mental health, and community support services collaborated to identify workflows, formulate goals, manage logistics, and review case details. Each of these disciplines had valuable and varying perspectives, all of which contributed to understanding the issue of unsubmitted SAKs in Houston and Detroit.

The teams from Houston and Detroit evaluated their sexual assault responses through open communication and a committed partnership, creating a culture of trust and understanding. Developing these relationships allowed both communities to gain a deeper understanding of the various perspectives, motivations, and responsibilities of each organization represented on each team.

One of the first things we learned is that this is not something just for property rooms and crime labs to deal with. Although testing kits is part of the solution, it is only one part. Work load then flows downstream â to investigators, prosecutors, and victim advocates â which is why it is so important to think holistically in terms of a system response.

âBill Wells, Research Partner, Sam Houston State University

MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAMS WERE VALUABLE FOR THE DETROIT AND HOUSTON ACTION RESEARCH PROJECTS BECAUSE EACH MEMBER BROUGHT UNIQUE EXPERTISE.

Discovering The Issues

Discovering Issues, Developing Solutions

The first step Houston and Detroit took was to conduct a census of the SAKs in police custody to determine how many kits they had, and how many had or had not been tested. Both cities also began by analyzing small groups of kits, developing and documenting the process. They identified challenges they would need to resolve, such as how much information to gather about each kit, how much time and how many personnel would be needed to conduct a full census, and how the chain of custody would be preserved. Other jurisdictions may want to consider other census tasks, such as developing a tracking database and making pre-arrangements for the laboratory to test a large number of kits.

BOTH HOUSTON AND DETROIT CONDUCTED A CENSUS TO DETERMINE HOW MANY UNSUBMITTED SEXUAL ASSAULT KITS THEY HAD.

We didnât want to rush in and take action without understanding the nuances of the situation. [We] wanted to understand the issues so we could craft responses that stood the best chance of succeeding.

â Bill Wells, Research Partner, Sam Houston State University

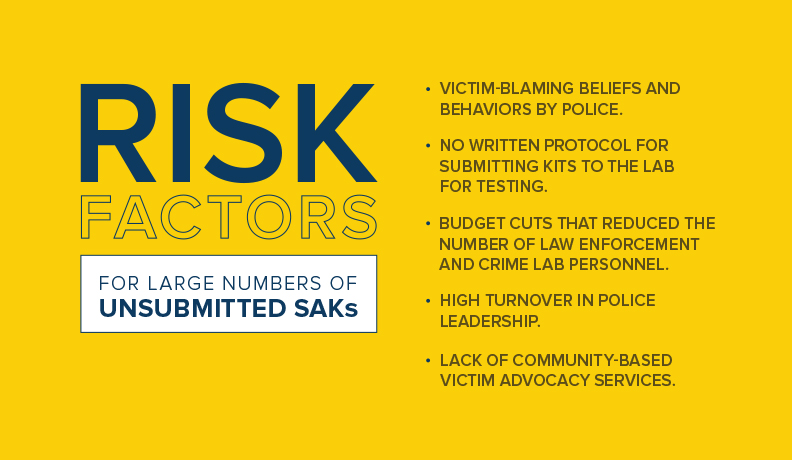

Another question Houston and Detroit sought to answer was why kits were not submitted to the lab at the time the assault occurred.

Previous research and anecdotal information have revealed a number of reasons that police in the past did not send a kit for testing. In many sexual assault cases, for example, the victim knows the perpetrator, and the police might not send a kit to the lab because they do not need to confirm the identity of the suspect. But, we are learning through research that as the national DNA database grows and DNA from cases with known suspects are entered into the national database, investigators are more likely to find leads to other crimes, including other sexual assaults.

Reasons why kits were not sent to the lab are likely to vary from one jurisdiction to another.

Detroit Identified Five Reasons Why Kits Were Not Submitted to the Lab

History Matters

To understand how such large numbers of untested SAKs have accrued, history matters. In 1994, Congress authorized the National DNA Index System (NDIS), but modern DNA forensic analysis was not widely used until the late 1990s. A database is only as robust as the amount of information in it. It took years to build up the number of profiles in the database â for law enforcement to begin to routinely submit DNA samples, and for crime labs to complete the extensive processes to qualify and upload DNA profiles into the database. In Detroit, for example, the crime lab had provisional ability to upload profiles into the database starting in 2002, but did not achieve full capability until 2006. Until at least the early 2000s, the use of DNA databases was not common across the nation.

The Importance of Modern IT

The availability of computerized evidence-tracking systems is a significant issue with many jurisdictions in the nation facing severe information technology (IT) challenges. In some places, one person in the police department maintains a single spreadsheet for managing and tracking evidence in the property room. It isn't easy to figure out what evidence needs to be tested, let alone determine the status of the case. During the action research projects, the teams in Detroit and Houston worked with IT experts to develop centralized databases containing information about all SAKs in police custody. Having a robust, automated tracking system gives a jurisdiction a vastly improved capacity to evaluate the funding, staffing, and other resources they need to test kits, do follow-up investigations, and prosecute a suspect.

DNA Testing

The Science of Kit Testing

Forensic testing of potential evidence in a SAK is a complex process that can take several days and include multiple testing stages. NIJâs scientific investments over the years have produced significant improvement in the technology and methods used to test kits.

Studies are making it possible for labs to reduce the time and cost of testing.

Rather than test each sample one at a time, for example, most labs today can now routinely test multiple samples simultaneously and better isolate mixed DNA samples.

When processing evidence, lab practitioners typically consider:

- The police report and the victim's statement of what happened to help the analysts determine how best to process the evidence and which pieces of evidence are most likely to contain biological material (saliva, skin cells, blood, semen).

- The time between the assault, the forensic exam, and when the kit is opened in the lab; biological evidence can deteriorate over time, and older evidence is processed differently from evidence that was collected recently.

A DNA profile by itself is fairly useless because it has no context. DNA analysis always requires that a comparison be made between two samples.

â Detroit Sexual Assault Kit Final Report

What is CODIS?

The FBI's Combined DNA Index System, known as CODIS, is the national criminal DNA database. CODIS was established by Congress to assist in providing investigative leads for law enforcement. The National DNA Index System (NDIS) is one part of CODIS, containing the DNA profiles contributed by federal, state, and local participating forensic laboratories. DNA profiles are uploaded to NDIS from evidence collected at crime scenes, from convicted offenders and arrestees, as well as from missing persons and unidentified remains.

A âCODIS hitâ can occur in two ways. The first is when a DNA profile developed from evidence in an SAK is uploaded to CODIS and matches to an offender or arrestee profile in the system. The second way is a case-to-case hit in which an unidentified DNA profile matches an unidentified profile from another case. If there is a potential match, the laboratory will go through procedures to confirm the match. If the match is confirmed, a CODIS hit can give investigating officers valuable information to help them focus their investigation and identify potential suspects. The more DNA data is entered into this system, the more likely it will be to produce meaningful leads on crimes.

Detroit Findings

What Detroit Found

The Detroit team discovered 8,707 untested kits. The city eventually decided to test all of them, and the team decided to randomly select a small portion to study in depth to understand what outcomes might occur under different circumstances. They hoped to provide data that would help other jurisdictions.

The team randomly sampled 1,595 cases and sorted them into four categories:

- Stranger-perpetrated sexual assault: The victim did not know the identity of the suspect.

- Non-stranger-perpetrated sexual assault: The suspect was identified by the victim.

- Cases that were presumed to be beyond the statute of limitations.

- A comparison of traditional and selective degradation DNA-testing methods.

The results of the experiment showed similar results for all four types of cases: similar percentages in the number of profiles eligible to be entered into CODIS, similar percentages of CODIS hits, and a similar ability to help identify instances of serial sexual assaults.

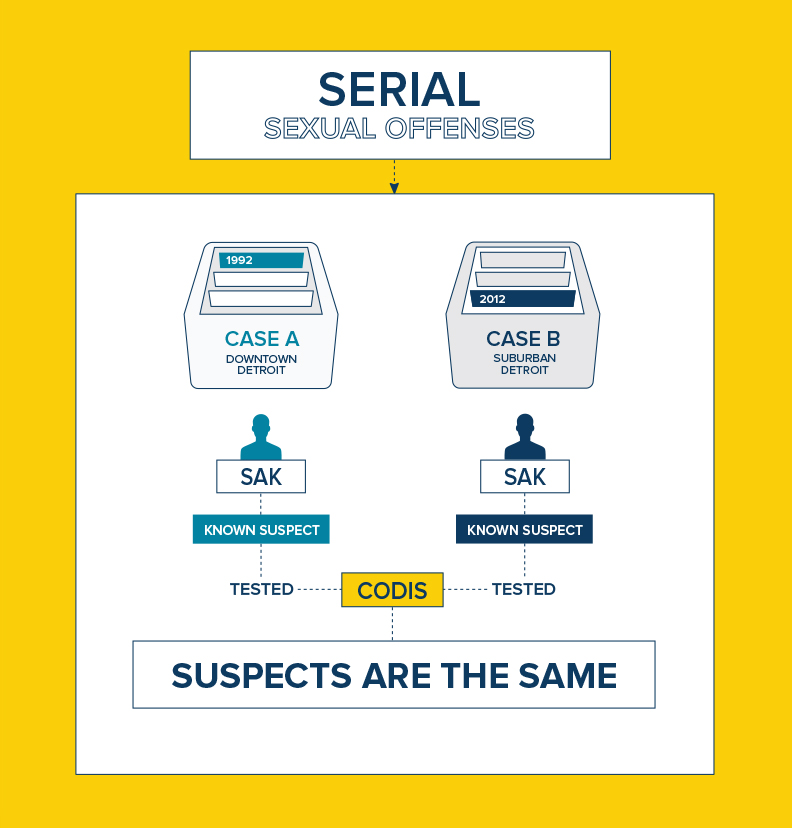

In the past, if the suspect's identity was known, police may not have submitted the kits to the lab for testing. In Detroit, however, the study of 1,595 randomly selected SAKs revealed that testing kits involving known suspects produced CODIS hits showing that the suspect committed other offenses, including sexual assaults.

The Detroit action research project revealed that testing kits involving known suspects could identify serial sexual offenders.

Other jurisdictions may find very different results. Additional research is underway to learn more about serial rapists and the value of testing kits when the police have a suspect.

In addition, the Detroit research team conducted a randomized experiment on 400 cases to compare two DNA-testing methods: the traditional method and a new method called selective degradation. In selective degradation, the forensic scientist uses a fasterâacting chemical technique for isolating the sperm and destroying the remaining nonâsperm cells in the sample. The technique minimizes mixtures in the sample while leaving any sperm mixtures intact (if there are multiple male assailants).

The results showed that the selective degradation method was as accurate as the traditional method, and the rates of profiles eligible for CODIS entry were very similar. Selective degradation takes scientists less time to interpret and review the test results, so it could be a promising method for laboratories to save personnel costs without sacrificing testing quality.

Victim Notification

Victim-Centered and Trauma-Informed

When a sexual assault occurred a long time ago, and the victim has not heard anything since agreeing to the exam, notifying them about new information is complicated. Victims, for example, may no longer want to take part in an investigation or may fear being retraumatized.

A goal of the action research projects in Detroit and Houston was to develop victim notification protocols that were victim-centered and trauma-informed.

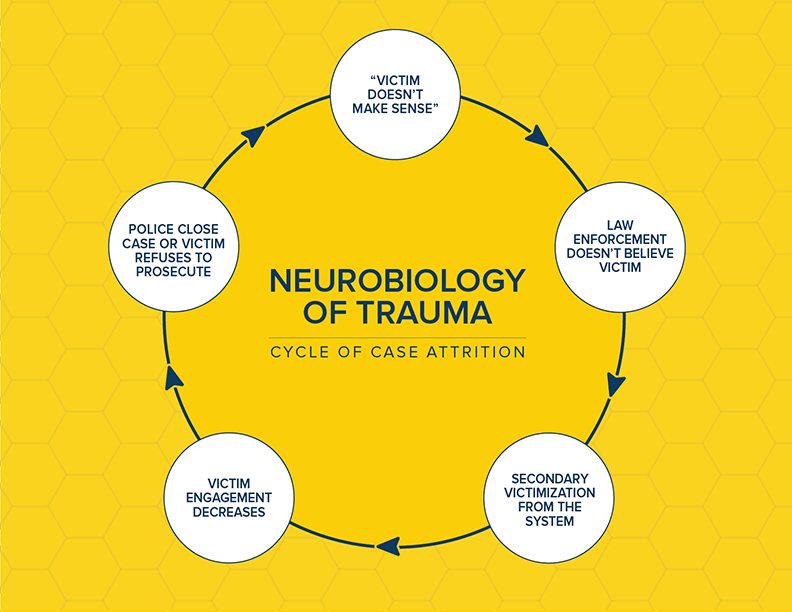

Both Detroit and Houston saw the need to train their criminal justice professionals on the victims' neurobiological response to sexual assault. For example, victims of trauma may behave in ways that are confusing to themselves and others, or may find that their recollection of events comes slowly and in fragments. Research has shown that the quality of statements can be enhanced by allowing victims to tell their stories at their own pace, understanding that their account may not come out in chronological order, and that details may be fuzzy.

The teams in both Detroit and Houston developed and implemented victim notification protocols for cases where a SAK was previously untested. In Detroit, the team established in-person notification and offered an apology when testing of a SAK yielded a CODIS hit. The in-person notification was done by representatives from the prosecutor's office, not the police department. Victims were also offered options for confidential communication (including whether or when to follow up with investigators or a community advocate) and were connected with community services.

One of the victim notification protocols in Houston included creation of a hotline for victims of sexual assault to contact authorities to learn the status of their cases, including results of the DNA testing. The hotline was advertised through public service announcements online and in pamphlets left at community centers.

The Houston Police Department also hired a specialist, called a âjustice advocate,â to help sexual assault victims navigate the criminal justice system. To better understand the impact the justice advocate position had on sexual assault investigations, the Houston action research team held focus-group sessions with detectives. The response was so positive that when results were presented to leadership, the position was made permanent.

As the nation grapples with how to better respond to sexual assault, using victim-centered and trauma-informed policies and practices is critical. Such approaches can provide victims access to the justice system, enhance victim services and responses, and improve public safety.

What happens to the brain and body during a sexual assault?

Sexual trauma directly affects parts of the brain that control memory, cognition, and emotion processing. Because the brain detects a threat, it activates a flood of hormones. The brain is highly sensitive to these severe fluctuations, and the hormones can:

- Impair rational thought and memory consolidation.

- Reduce energy and may cause âtonic immobility,â or temporary muscular paralysis.

Victims may experience âflat affect,â show little emotion, or have emotional responses that seem unusual given the circumstances, such as laughing or smiling while being questioned, often leading investigators to not believe them. Their memories of the trauma may also be fragmented and disoriented, so recalling events can be a slow and difficult process, and their statement may come out as evasive or âsketchy.â In addition, because of the lack of knowledge about what tonic immobility is, victims may feel increased self-blame, and police investigators may misinterpret this as consent.

Having a basic understanding that there is a wide range of reactions to a traumatic event that may not seem âtypicalâ â and that the body's attempt to defend itself from a threat can affect these reactions â is important for every criminal justice professional to understand. Teaching law enforcement officials that it may take more time and patience for a victim's memory to come together â and that a victim's reaction to fight, flee, or freeze is uncontrollable behavior â may help investigators and prosecutors down the road.

Future Response

Future Responses to Sexual Assault

Science is helping our nation move forward in developing better responses to sexual assault â better interviewing of victims, better tracking of evidence, better investigation and prosecution, and better ways to support victims.

This is not a Houston problem. Itâs not a Texas problem. Itâs a nationwide issue that built up over years and years.

â Anise Parker, Mayor of Houston

Although the research projects in Detroit and Houston produced policies and practices that are unique to the circumstances in those communities, lessons learned from their experiences may apply elsewhere.

Although the research projects in Detroit and Houston produced policies and practices that are unique to the circumstances in those communities, lessons learned from their experiences may apply elsewhere.

Other jurisdictions that are facing similar issues with a large number of previously untested SAKs may want to consider the following:

- How do law enforcement, prosecutors, victims' services, medical professionals, and forensic laboratories work together to address the testing of large numbers of SAKs?

- What should be considered when developing a database for tracking evidence that goes to the lab for testing?

- Who should be trained to understand the trauma of sexual assault and how to work with victims?

- Is there a written, victim-centered and trauma-informed victim notification protocol for both current sexual assault cases and cases where the SAK was not previously tested?

- How can police work with victim advocates and community services to improve the investigation and notification process?

- How should priorities be established for the order in which SAKs are tested?

- What are the cost implications for testing large numbers of unsubmitted SAKs and any follow-up police investigations and prosecutions?

- What new technologies can be adopted to increase the capabilities of the forensic lab?

Resources

- Multidisciplinary Sexual Assault Glossary

- Five Things About Sexual Assault Kits, a fact sheet about DNA testing of sexual assault kits.

- âTaking on the Challenge of Unsubmitted Sexual Assault Kits,â webinar with Rebecca Campbell, Noël Busch-Armendariz, Bill Wells, and Mary Lentschke. Moderated by Bethany Backes.

- The Road Ahead: Unanalyzed Evidence in Sexual Assault Cases, May 2011.

- Down the Road: Testing Evidence in Sexual Assaults, June 2016.

- Sexual Assault Kits video interviews with Rebecca Campbell, Noël Busch-Armendariz, Bill Wells, and Caitlin Sulley

- A series of guides providing lessons learned:

- Performing an Audit of Sexual Assault Evidence in Police Custody (pdf, 16 pages)

- Forming an Action-Research Team to Address Sexual Assault Cases (pdf, 12 pages)

- Creating a Plan to Test a Large Number of Sexual Assault Kits (pdf, 16 pages)

- Notifying Sexual Assault Victims After Testing Evidence (pdf, 20 pages)

- Houston Sexual Assault Kit Research, a website devoted to the Houston multidisciplinary team's approaches, processes, and research findings.

- Untested Evidence in Sexual Assault Cases, a webpage that discusses the findings of NIJ-supported research on sexual assault evidence.

- The NIJ-FBI Sexual Assault Kit Partnership â A Research Initiative for Unsubmitted Sexual Assault Kits, a webpage that provides information from the NIJ & FBI partnership to address unsubmitted sexual assault kits.

- A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensics Examinations: Adults/Adolescents (Second Edition), U.S. Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women.

- A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensics Examinations: Pediatrics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women.