When the doors close and the bell rings, students put their trust in their schools to keep them safe, both mentally and physically. Given that the climate of the entire school is influenced by peer aggression and student victimization, schools trying to keep their students safe are eager to know more about the effectiveness of school-based mental health services.

Many schools offer mental health services, which vary between schools, but often include access to counselors, psychologists, or social workers who can provide prevention programming, early identification of mental health challenges, and treatment options. Two particular types of evidence-based treatments, dialectical behavior therapy and structured psychotherapy for adolescents responding to crisis, have the potential to benefit students, but their efficacy in the school setting has not yet been tested.

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy that offers evidence-based strategies for addressing mindfulness, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and emotional regulation. Structured psychotherapy for adolescents responding to crisis (SPARC) is a group treatment designed to improve emotional, social, academic, and behavioral functioning of adolescents exposed to chronic interpersonal trauma or other types of traumas.

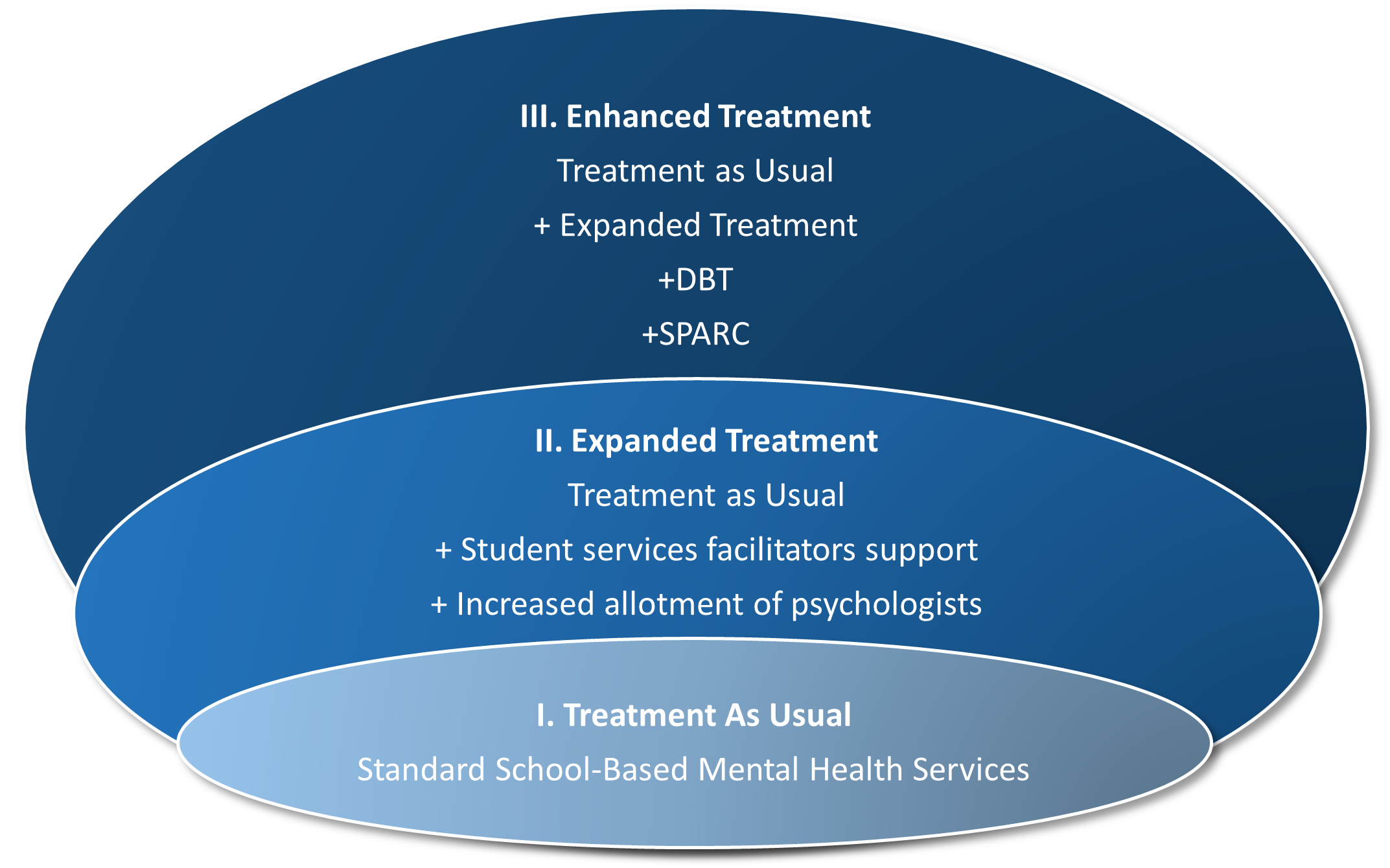

NIJ-funded researchers from RTI International partnered with Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina to conduct a randomized controlled trial focusing on evaluating the use of these types of mental health services in schools to help address safety. Thirty-four middle schools began participating in the project during the 2016-2017 school year and continued through the 2018-2019 school year. The study examined three levels of school-based mental health treatments: standard school-based mental health services, expanded treatment, and enhanced treatment (see Figure 1). In addition, researchers conducted a quasi-experiment design comparing the various treatment options to schools not providing any school-based mental health assistance.

The primary study goals were to:

- Implement dialectical behavior therapy and structured psychotherapy for adolescents responding to crisis in schools selected for the enhanced treatment intervention.

- Test for differences in school-level changes in student well-being and school safety among the three forms of school-based mental health treatments.

- Assess the cost effectiveness of each of the school-based mental health models.

- Develop recommendations for the use of school-based mental health services, dialectical behavioral therapy, and structured psychotherapy for adolescents responding to chronic stress.

Variation in Implementation, Mixed Results in Staff and Student Sentiment

Researchers measured outcomes using student, staff, and administrative survey data collected from the fall of 2016 to the spring of 2018. Survey topics included school safety, violence, and victimization and reflected the experience of the people in the school, including the entire staff and student bodies, not only those involved in school-based mental health services.

- In implementation, the researchers found that services did not differ by treatment group in the way they expected. The assessment of the time spent on each student and the percentage of students served by therapists, psychologists, and counselors revealed that the treatments thought to be the most time-intensive did not necessarily take up the most time, but instead varied by the schools (indicating differences in implementation).

- Regarding sentiment, most of the surveyed staff reported feeling safe before, during, and after school, but also reported observing unsafe behaviors (e.g., bullying) during the past 30 days. Student sentiment results were mixed when comparing treatment groups, showing improved effects in some outcomes but not others in the groups that received school-based mental health over those that did not.

- Infractions due to fighting, bullying, aggressive behavior, and disruption showed no significant difference among the three experimental groups. However, insubordination and disrespect were reduced in the expanded treatment and enhanced treatment groups, relative to the treatment as usual group.[1]

- Student victimization, as measured through both self-reported sentiment and infractions data, showed improvement across time in the Enhanced and Expanded intervention groups compared to the group that only received standard school-based mental health services. Given the greater cost associated with Enhanced treatment, the authors suggest that the Expanded treatment is the most cost-effective option to reduced student victimization.

Interviews Corroborate Quantitative Findings, Illustrate Barriers to Implementation

Provider interviews supplemented the quantitative survey findings by illustrating the challenges faced in implementing dialectical behavior therapy and structured psychotherapy for adolescents responding to crisis. Chief among the providers’ concerns were a lack of time (especially for time-intensive services for students with chronic stress) and competing administrative responsibilities. Provider turnover and mixed attitudes of school administrators toward engaging in such intensive treatments were also noted as barriers to implementation.

The RTI research illustrates the challenges involved with introducing and implementing intensive, evidence-based treatments in schools. The expanded and enhanced treatments did not result in the outcomes that the researchers had anticipated, perhaps because the treatments were not implemented as planned. The intensive training and time commitment that was required to implement the interventions may have reduced the amount of time providers could actually spend with the students. Researchers posit that meeting students’ mental health care needs and improving safety in their schools may require additional providers with more time to devote to the provision of school-based mental health services.

On the bright side, surveys indicated that providers tended to be willing to practice evidence-based interventions. Importantly, such willingness was significantly correlated to the school’s readiness to adopt evidence-based interventions — suggesting more opportunities to improve the implementation of school-based mental health services and ultimately school safety in the future.

About This Article

The work described in this article was supported by NIJ award number 2015-CK-BX-0010, awarded to Research Triangle Institute.

This article is based on the grantee report “School Safety and School-Based Mental Health in a Large Metropolitan District” (pdf, 153 pages), by Anna Yaros, James Trudeau, Jason Williams, Antonio Morgan-Lopez, Alex Buben, Stefany Ramos, Lissette Saavedra, Terri Dempsey, Alan Barnosky, Alex Cowell, Sherri Spinks.