The challenges involved in preventing domestic radicalization and violent extremism include the fact that people who are radicalized or engage in violent extremism often have experienced trauma and have mental health conditions. Research suggests that for some individuals, these issues may contribute to their involvement in domestic radicalization or violent extremism. For example, a person’s vulnerability may lead them to an ecological niche where recruiters offer a supposed better path. Fortunately, only a small minority of people with trauma exposure and mental health issues have taken such a path, and many others do so without any apparent trauma or mental health concerns. Nonetheless, attending to these issues could prove fruitful in preventing radicalization and extremist acts.

Law enforcement, governments, and communities have increasingly employed innovative approaches when responding to individuals involved in domestic radicalization and violent extremism. They have learned that they can further prevention efforts by better attending to trauma and mental health. Yet questions remain regarding the effectiveness and scalability of such approaches. Moreover, law enforcement, government, and community responses may inadvertently exacerbate trauma exposure and mental health issues for some individuals in ways that can complicate efforts to prevent radicalization.

Understanding and addressing the complexity of trauma exposure and mental health issues relative to domestic radicalization and violent extremism remains a major challenge. Multidisciplinary research can help unpack this complexity. This article discusses three studies funded by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) that illustrate how trauma and mental health issues are neither necessary nor sufficient to explain domestic radicalization and violent extremism.[1] However, when present, these factors can have a significant yet varied impact across the violence prevention spectrum. This knowledge — along with additional perspectives based on trauma-informed care — can help strengthen programs and policies and guide recommendations.

Pathways to and Away From Violent Extremism in a Community Sample

In the first NIJ-supported study, researchers from the Children’s Hospital Corporation sought to understand the pathways to diverse outcomes among Somali immigrants: Why do some show greater openness to violent extremism while others, with shared life histories, move toward gangs, crime, or resilient outcomes such as civic engagement?[2] Using a community-based participatory approach, the researchers conducted a mixed-methods study to explore structural adversity, mental health, and openness to violent extremism among a community sample of 394 ethnic Somali young adults in the United States and Canada. Young Somali adults in North America offer a window into the remarkable potential that refugees and immigrants can realize despite experiences of severe adversity and challenges often encountered when adjusting to life in a new country. In addition, the Somali community in the United States has simultaneously faced gang violence and the threat of youth radicalizing.

The researchers categorized participants into five groups based on key attitudinal and behavioral variables of interest:[3](1) participating in delinquent behaviors, (2) civically engaged, (3) civically unengaged, (4) radical beliefs/civically unengaged, and (5) radical beliefs/civically engaged (see exhibit 1). This initial categorization was made at Time 1. One year later (at Time 2), an analysis revealed similar groupings, suggesting that these groupings were meaningful across time. Importantly, the vast majority of these young Somali adults neither participated in nor expressed support for the use of violence. In addition, the civically engaged group had the largest proportion of participants at both Times 1 and 2.

Exhibit 1. Categories of Participants

The researchers found that the number of participants in each group changed over time, and so they examined how likely it was that participants were still in their initial group one year later (known as stability rates). They found that the presence of a negative event — for example, personal or societal obstacles such as higher levels of depression or anxiety, experience of discrimination, or poor interaction with law enforcement — was associated with less stability and slowed down the transition from the radical beliefs/civically engaged group to the civically engaged group. Without taking into account adverse experiences, 32% of individuals moved from the radical beliefs/civically engaged group to the civically engaged group. The share of people who moved from radical to civically engaged was remarkably lower in the presence of a negative event, declining 32% to 14.5%.

All groups experienced structural adversity (trauma and discrimination). At Time 1, moderate levels of structural adversity were associated with group membership in three of the five groups (all except the delinquent and civically unengaged group), suggesting that moderate adversity may catalyze a desire for change in some way, whether through legal (civic engagement) or illegal/violent (radical belief) means. Life experiences may play a role in determining group membership. Overall, a strong sense of attachment to one’s country of resettlement (in this case, the United States or Canada) was associated with less openness to violent extremism. One possible interpretation is that exposure to moderate adversity may catalyze a desire for change; the degree to which young adults feel a sense of belonging and attachment to their country may drive, to some extent, whether they seek this change through legal or illegal/violent means.

The findings support the idea that there is no single pathway to openness to violent extremism, nor is there a single type of individual most vulnerable to being open to violent extremism.[4] This has implications for policy and programming. For example, individuals who showed openness to violent extremism varied in their behaviors and attitudes. To prevent violent extremism, program developers and policymakers must consider various ways to reach diverse young adults and recognize that the drivers of openness to violence for community members may be different. In addition, efforts to protect young adult community members from negative events may enhance movement toward nonviolence and constructive civic engagement. Community members listed positive interactions with law enforcement at community events — such as officers educating newer immigrants about the law — as an example of a protective effort.

Sharing Terrorism-Related Information With Authorities

What can people who are close to someone on the pathway to terrorism or targeted violence do to help? The first people to suspect or know that someone is planning targeted violence or terrorism are often their family, friends, co-workers, and classmates. These people are referred to as “intimates.” Information about a planned attack that “leaks” — either intentionally or unintentionally — to these individuals makes them “intimate bystanders” (and distinguishes them from bystanders with no close relationship).[5]

International prevention strategies typically encourage intimate bystanders to report targeted violence or terrorism. In the United States, information and educational resources to support intimate bystander reporting of possible violent extremism have yet to be widely available, and intimate bystander reporting remains more of an exception than the rule. Further, intimate bystanders have their own cognitive factors, mental health concerns, and traumas that pose barriers to reporting. Future programs must address these issues in order to succeed.

NIJ-funded researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Illinois at Chicago studied whether a diverse sample of community members would consider reporting friends or family who they suspected to be planning terrorism or targeted violence.[6] They found that complex emotions, feelings, fears, and traumas greatly influenced reporting. Fears and anxieties about the consequences of reporting weighed against their care and concern for both the individual and the broader community. Along with the common fear of being viewed as a “snitch,” intimate bystanders feared family or community backlash, being ostracized, harming their relationship with the individual, and retaliation.

The researchers particularly found noteworthy the intensity with which intimate bystanders were afraid to involve law enforcement before someone had committed a crime because of the possibility of an overreaction, including police violence. This concern was not limited to those belonging to racial or ethnic minority groups. Intimate bystanders who identified as white also feared this response. They doubted law enforcement’s ability to prevent violence and feared the potential for escalation.

The researchers found that community members instead want to get help and advice from other intermediaries without criminalizing or endangering the individual they suspect to be planning terrorism or targeted violence. Intimate bystanders prefer to seek help from mental health or other community professionals, such as a social worker or a faith-based leader, particularly when the individual is a family member or friend (as opposed to a co-worker). They also favored seeking advice from a community-based professional before they report to law enforcement, potentially delaying prevention. Many viewed reporting directly to law enforcement as a last resort.

When intimate bystanders view the potential for violence as a mental health concern, they might seek advice and guidance from mental health practitioners on whether and how to report. In this case, the practitioners could provide counseling to the person at risk and make a formal report to law enforcement on the intimate bystander’s behalf, if necessary. Unfortunately, study participants said that accessing mental health services is difficult. A formidable obstacle is the high cost of mental health care. People living in rural and exurban communities also face a shortage of mental health professionals. The lack of mental health professionals trained in how to address someone who might perpetrate violence also likely exacerbates the problem.

Traumatic experiences related to law enforcement are also important. Intimate bystanders hesitate to ask police for help due to experiences with or knowledge of local law enforcement violence and racial discrimination, fearing similar treatment. The researchers found that willingness to report to law enforcement depended on their reputation for violence and discrimination. Intimate bystanders expected law enforcement to respond more harshly to a person who belongs to a racial minority group. Thus, multiple factors combine to impede reporting.

Given these fears and concerns, the researchers recommended the following set of supports to help facilitate intimate bystanders’ willingness to initiate reporting:

- Make counseling and mental health support available from the time someone considers reporting to after they make the report. This can help ease fears as intimate bystanders navigate the emotionally challenging process of reporting a loved one.

- Train community practitioners in targeted violence prevention. These practitioners can partner with law enforcement to form a threat assessment response team that facilitates prevention.

- Establish community outreach and educational initiatives about the availability of these support services.

- Improve reporting in order to confront institutional and societal factors, such as police violence, that shape intimate bystander reporting. A cohesive program for encouraging intimate bystanders to report must confront the fears and mistrust that arise from historical, personal, and community experiences of trauma resulting from racism and law enforcement violence.

Narratives of Radicalization and Deradicalization

Researchers at the RAND Corporation studied the pathways of radicalization and deradicalization among 36 former extremists (28 former white supremacists and eight former Islamic extremists).[7] One major takeaway from this NIJ-funded study was that profound and unexpected negative experiences often created a search for meaning that prompted budding extremists to look for new ways of interpreting the world. Such experiences ranged widely — from relationship dissolution to job loss to losing a close friend in military combat. But each created a sense of deep loss, disappointment, and existential crisis that created a desire to find meaning in life again. Former extremists described how “converting” to an extremist mindset helped them achieve clarity and purpose and find a reason (and punishable target) for their unhappiness. In some cases, the traumatic, negative life events led to social isolation; consequently, individuals sought a sense of social belonging and found it in radical groups and ideologies.

The study also revealed that recruiters for extremist organizations knew how to recognize and target the signs of social and emotional distress when recruiting new members. For example, recruiters for white supremacist groups recognized individuals who had been bullied and provided both a frame of reference for understanding “white victimization” and the need for whites to rally together. These recruiters even targeted towns that had recently undergone economic transformation and loss of major employers. Moreover, radical organizations often welcomed new recruits with events that featured camaraderie and social bonding; these ranged from community barbecues to organized involvement in street violence.

Former extremists and their loved ones described how, once they had converted to the radical extremist cause, the sense of being a member of an aggrieved minority group (but nonetheless part of a collective rather than alone or isolated) galvanized further involvement in the cause and provided some immediate relief from psychological distress.[8] However, former extremists also described how extremism itself could sometimes exacerbate distress, such as through involvement in substance use within groups or involvement in traumatic violence.

Although extremist groups seemed sufficiently adept at satisfying the social and emotional needs of individuals in order to gain and retain members, the former extremists also described how their continued distress opened opportunities for deradicalization. The most common feature of successful deradicalization among participants was the experience of love, kindness, and support — often from a member of a hated group. (For example, a Turkish immigrant provided employment and emotional support to a white supremacist.) In some cases, counter-radicalization groups orchestrated this exposure (for example, by bringing extremists into contact with former members of gangs who had left a life of violence). Sometimes these experiences of kindness and support blossomed into lifelong friendships or even romantic partnerships, which replaced the support and sense of meaning that radical extremist groups had provided.

These narratives and other studies[9] of deradicalization pathways provide hope that knitting together the social and emotional fabric of communities and individuals who have experienced loss and disruption could help decrease radicalization and increase exit from radical extremist groups. In other words, providing social and emotional support after traumatic life events may prevent extremist groups from using such experiences to recruit new group members. Furthermore, providing support and love in a patient and forgiving way may help coax more members out of extremist groups and, in some cases, lead them to help others exit as well.

However, such interventions are often profoundly time- and labor-intensive. The core challenges to implementation will be how to systematize this type of exposure to diversity, kindness, and social and emotional support so that they are features of the socioecology rather than rare, high-cost, reactive solutions. Importantly, such large-scale changes will also naturally decrease other negative outcomes, such as involvement in gangs and criminal violence, substance use, and family violence.

Trauma-Informed Practices Across the Prevention Spectrum

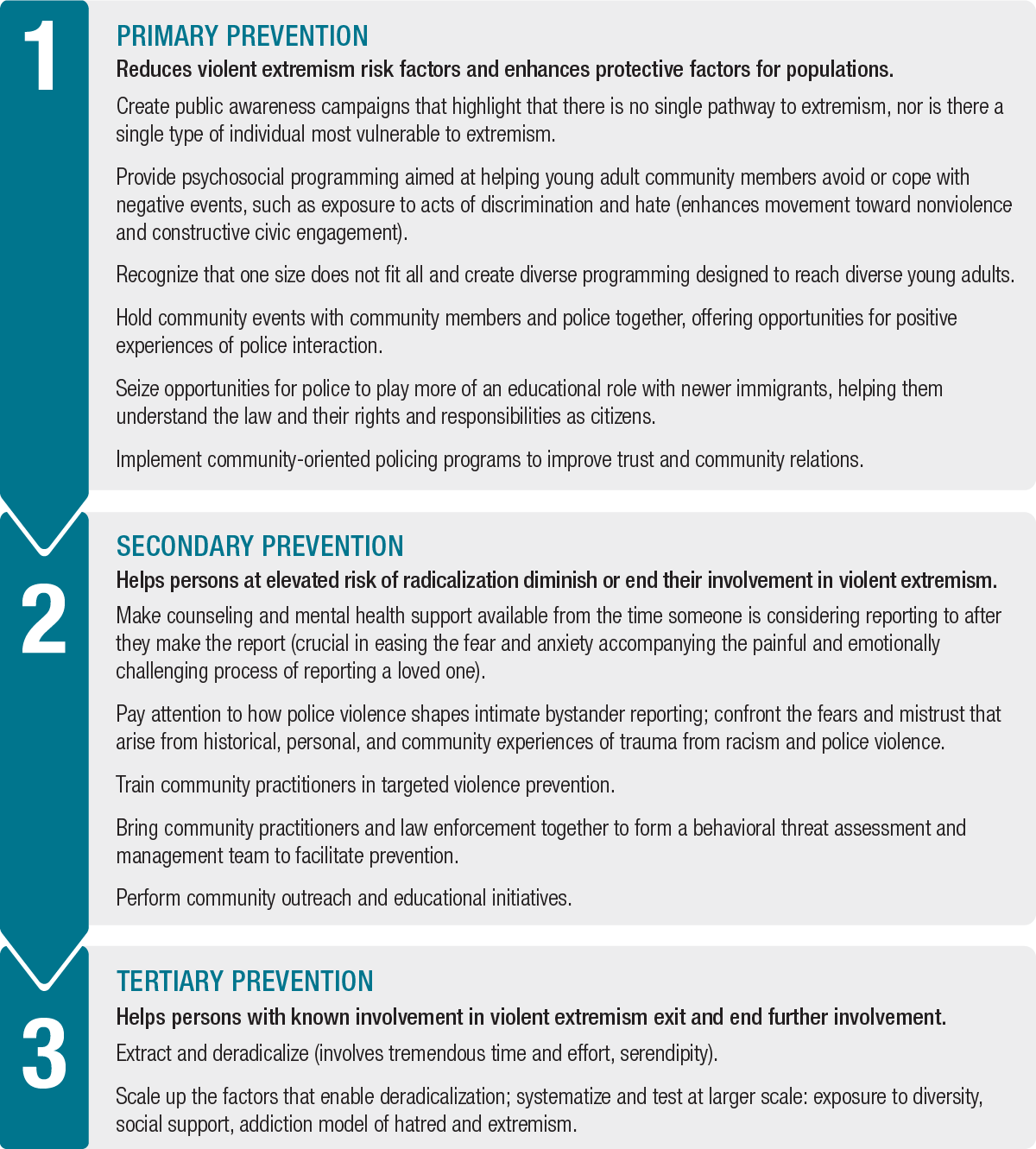

Trauma and its mental health consequences are not always part of a person’s development to violent extremism. But when they are involved — as described in these three studies — practitioners and policymakers should be aware so they can appropriately address them through a public health approach with prevention activities at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels (see exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2. A Public Health Approach to Addressing Domestic Radicalization and Violent Extremism

There are, however, important considerations:

- Trauma exposure is not only manifest in symptoms but also in worldviews, identities, and relationships to communities and organizations in ways that affect trust in institutions, decision-making, and actions.

- Contextual factors shape experiences of trauma and mental health issues. Therefore, researchers need to perform a deeper and more systematic examination of how economic, historical, cultural, and community factors may shape vulnerabilities — and appropriate responses to those vulnerabilities.

- Vulnerabilities associated with trauma exposure and mental health issues are not necessarily unique to violent extremism. They can be associated with many other negative outcomes, such as other criminal activity, suicide, or substance use. Therefore, prevention approaches for domestic radicalization and violent extremism must be integrated with other prevention goals and activities.

How do we take the emerging knowledge about vulnerabilities related to trauma exposure and mental health experiences and translate it into effective, scalable interventions across the prevention spectrum? One approach is to employ and adapt trauma-informed practices that have been designed for and applied in other systems, such as health care, education, and juvenile justice.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, a trauma-informed approach seeks to “[r]ealize the widespread impact of trauma and understand paths for recovery; Recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, and staff; Integrate knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and Actively avoid re-traumatization.”[10] In the United States, several major institutions — including the National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network — have developed, evaluated, and disseminated trauma-informed approaches through multiple systems.

There are several ways to expand core trauma-informed practices from these other systems into violent extremism prevention. One way is to focus on individual assessment. Individuals who are assessed for possible involvement in extremism and violence should also be assessed for trauma exposure and mental health consequences using widely available, standardized screening instruments and clinical measures. If present, trauma should then be incorporated into the comprehensive formulation of the case, especially as a possible driver for involvement in extremism or violence.

A second way of expanding trauma-informed practices is to focus on the proper management of trauma-related mental health and other behavioral consequences in individuals and families. For example, helping an individual better manage their mental health disorder or symptoms can be crucial to their movement away from extremism and violence.[11] Additionally, their involvement in extremism and violence often provides them with experiences that compensate for or alleviate their distress, and they cannot give up such involvement without other measures that provide such relief.

A third way to use trauma-informed approaches is to move beyond the realm of disorders and symptoms and instead focus on trauma’s impact in broader psychosocial experiences and well-being. For example, Kai Erickson focuses on trauma and communities and defines “communal trauma” as a loss of the social fabric that ties people together in communities.[12] Another example is moral injury, which can occur when, “in traumatic or unusually stressful circumstances, people may perpetrate, fail to prevent, or witness events that contradict deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”[13] Viewed from these perspectives, trauma can powerfully shape collective and individual experiences and identities, a process that needs to be better understood and addressed.

Trauma-informed approaches have been extended into the practices of risk communication, journalism, and memorialization to better acknowledge and process trauma-related disruptions. In the prevention of violent extremism, we need to better understand and address the broader impacts of trauma through public communications by law enforcement, other government agencies, community partners, and the media. We should simultaneously work to integrate trauma-informed practices as has been done in other systems, including juvenile justice and schools, while building the prevention system for violent extremism.

About This Article

This article appears in NIJ Journal issue number 285.

This article discusses the following awards:

- “Understanding Pathways to and Away From Violent Radicalization Among Resettled Somali Refugees,” award number 2012-ZA-BX-0004.

- “Community Reporting Thresholds: Sharing Information With Authorities Concerning Terrorism Activity,” award number 2018-ZA-CX-0004.

- “Research on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Insights From Family and Friends of Current and Former Extremists,” award number 2017-ZA-CX-0005.

Opinions or points of view expressed in this document represent a consensus of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position, policies, terminology, or posture of the U.S. Department of Justice on domestic violent extremism. The content is not intended to create, does not create, and may not be relied upon to create any rights, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law by any party in any matter civil or criminal.