Researchers Make the Difference

Action research occurs when practitioners work alongside researchers to design, implement, evaluate, and revise intervention programs. In the context of reducing gun violence, action research refers to law enforcement-researcher partnerships formed to address a specific, local gun violence problem. These police-researcher partnerships usually involve other partners.

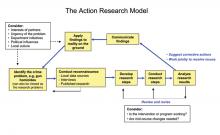

The criminal justice action research model. The action research model shown here represents a process that had its first trial by fire with Operation Ceasefire. Some version of this approach has been used by intervention programs, with varying degrees of success, ever since.

The Action Research model relies heavily on collaboration, feedback, innovation and compromise. It is illustrative — no one model will apply for every situation.

The process generally starts out with a working group or task force made up of law enforcement, community partners and university researchers. The working group meets to determine the crime problem, study the available data about it (crime reports, emergency room gunshot victims, incident reports, known gang members, etc.), and devise a solution based on what the local practitioners and community service groups know about the problem and what researchers know about best practices. As the researchers analyze the findings, these are relayed back to the group. If findings reveal that an intervention is not reducing gun crime, the researchers may suggest adjustments to the intervention. Sometimes, practitioners encounter an unanticipated reality in the field that requires working with the researchers to redesign the intervention.

This process often requires innovation and can be difficult, as described by the researchers involved in designing Boston's Operation Ceasefire (bolding added for emphasis):

[W]orking with YVSF, probation, and Streetworker members of the Working Group, plus several other police and Streetworker participants whom they recommended, the authors mapped gangs and gang turf and estimated gang size. This process identified some 61 different crews with some 1,300 members (the map of gang turf coincided almost perfectly with the homicide map). … Another step in the mapping process produced a network map of gang "beefs" and alliances: who was feuding with whom and who allied with whom. … Finally, working with the same group of practitioners, the authors systematically examined each of the 155 homicides and asked the group members if they knew what had happened in each instance and whether there had been a meaningful gang connection. This answer, too, was striking: Using conservative definitions and methods, at least 60 percent of the homicides were gang related. Most of these incidents were not in any proximate way about drug trafficking or other "business" interests; most were part of relatively longstanding feuds between gangs.

None of these dimensions — the number of crews, their size, their relationships, or the connection of gangs and gang rivalries to homicide — could have been examined from formal records; the relevant information simply was not captured either within BPD or elsewhere. But the frontline practitioners in the Working Group had this knowledge, and obtaining it by qualitative methods was a straightforward if laborious and time-consuming task.[1]

Despite months of this type of detailed findings and analysis, the Boston working group still had not come up with a strategy that worked when an unexpected breakthrough made the difference — the researchers' persistence in gathering information from caseworkers and officers uncovered a strategy that had been successful but not widely used or recognized. When this strategy was crafted and implemented on a larger scale, gun-related homicides in Boston fell nearly 70 percent in one year.

Learn more about Operation Ceasefire.

Researchers also can help law enforcement partners develop and stick to an evidence-based approach, which calls for (1) testing and validating police activities to develop policy and program guidelines based on best practices, and (2) careful monitoring of outcomes to ensure the program is working.

Police-researcher partnerships are vital for action research. Action research works best when police set aside their reservations or "turf issues" and researchers are flexible and sensitive to law enforcement concerns and priorities.