Targeted violence spans a wide array of offenses, from mass shootings to gang or group-violence-related activities to human trafficking. Although each of these topics has been researched extensively, until recently they have not been studied to identify similarities and differences in the context of domestic violent extremism and terrorism. Gaining a better understanding of any links or overlaps between people who perpetrate these types of violence and those engaged in violent extremism and terrorism is essential to developing or adapting targeted violence prevention efforts.

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) has funded multiple projects that compare individuals who perpetrate violent extremism and terrorism and those who engage in other forms of targeted violence.[1] This article reviews findings from several NIJ-supported projects that explore similarities and differences between:

- Violent extremists and individuals who are involved in gangs.

- People who engage in terrorism and those involved in human trafficking.

- Lone actor terrorists (that is, single individuals whose terrorist acts are not directed or supported by any group or other individuals) and persons who commit nonideological mass murder.

Some of these projects draw on large national databases of individuals who are known to have committed violent acts, while others explore community and stakeholder perceptions of the acts. In addition, some of these projects focus on how communities that contend with heightened risk factors, such as adversity and disadvantage, experience certain types of violence.[2] The article closes with a discussion of possible implications for policy and future research.

Violent Extremists and Individuals Involved in Gangs

Pyrooz and colleagues developed a comparative model that emphasizes explicit, spurious, and indirect links between violent extremist groups and criminal street gangs. Using national data sources on domestic extremists and individuals involved in gangs — the Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), respectively — the researchers compared the two groups across group involvement and demographic, family, religious, and socioeconomic status characteristics.[3] They found that 6% of domestic extremists in PIRUS have a history of gang ties; this constitutes a minimal proportion of domestic extremists and is likely the rare exception among those involved in gangs. Domestic extremists with gang ties more closely resemble nongang extremists in PIRUS than they do individuals involved in gangs in the NLSY97. Although these groups have some similarities, one major difference is that individuals involved in gangs are younger than domestic extremists. This likely contributes to many of the other differences between the groups across the life course, including in education, unemployment, marriage, and parenthood.

A critical step in determining similarities is to examine the circumstances of those who enter these two groups. Based on 45 in-person interviews of individuals involved in U.S. gangs and 38 life history narratives of individuals who radicalized in the United States, Becker and colleagues provided a unique comparison of entrance into these groups by drawing on four broad group entry mechanisms:[4]

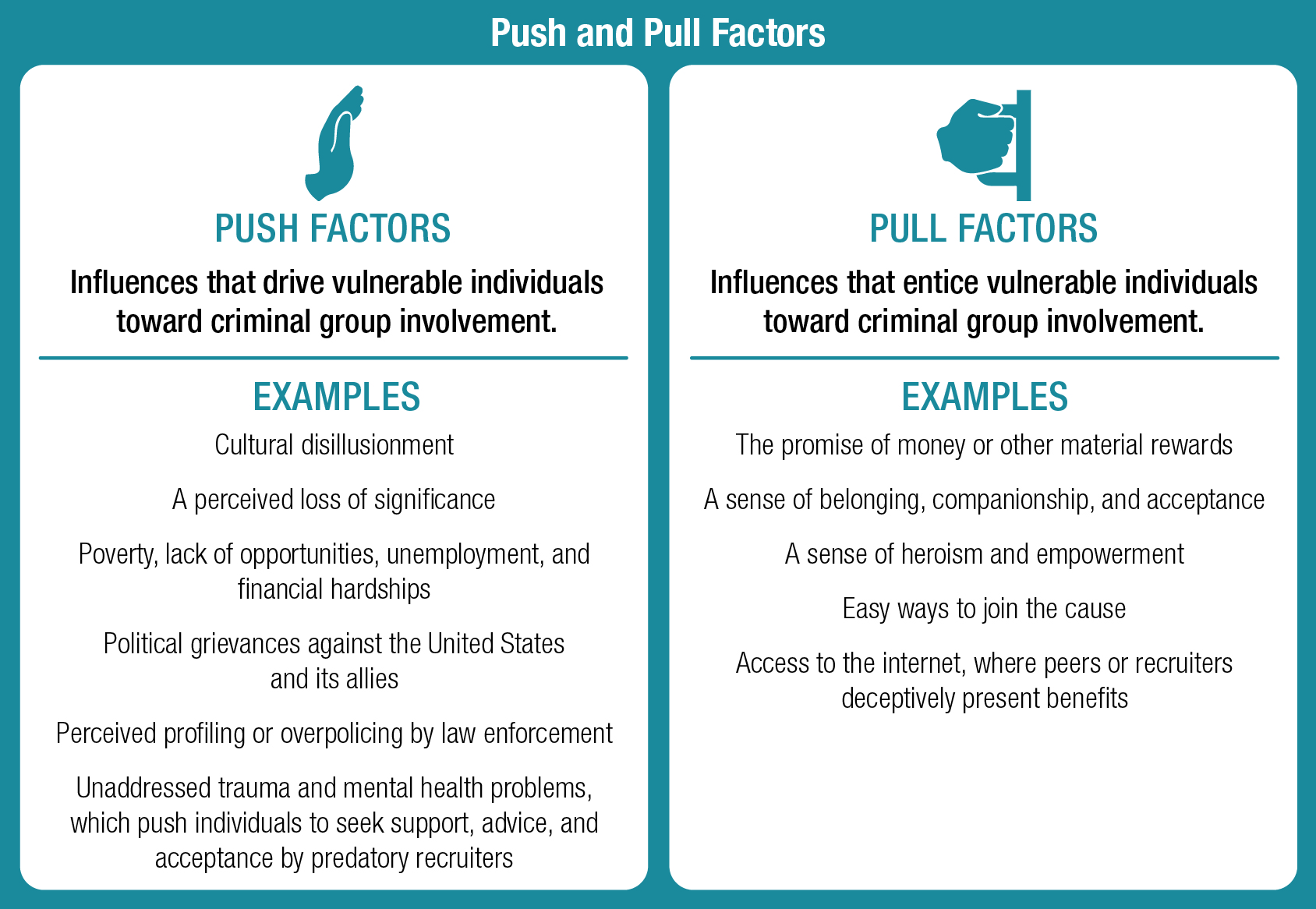

- Pull factors (influences that entice vulnerable individuals toward criminal group involvement).

- Push factors (influences that drive vulnerable individuals toward an interest in criminal group involvement).

- Barriers to effective socialization.

- Recruitment.

Individuals involved in gangs were more motivated than extremists by the promise of material rewards (a pull factor). In contrast, extremists were more motivated by cultural disillusionment and a perceived loss of significance (push factors). (For more detail on push and pull factors, see exhibit 1.) Individuals in gangs were more likely to have been abused by family members (a barrier to effective socialization), while extremists were far more likely to have been recruited through electronic media (recruitment). Evidence for each mechanism was present in both groups and no single mechanism dominated entry into either group. Thus, prevention and intervention efforts that draw on multiple pathways to entry are most likely to be effective.

Exhibit 1. Examples of Push and Pull Factors

In a separate community-based participatory research study, Ellis and colleagues explored attitudes toward gangs and violent political activism within a community sample of 498 ethnic Somali young adults living in the United States and Canada.[5] Somali communities in North America have been impacted by both gang violence and targeted recruitment by extremist networks; they have also disproportionately experienced structural disadvantages, such as poverty. The analysis showed that attitudes favoring both gangs and violent activism could — but did not necessarily — co-occur; prosocial bonds reduced the likelihood of attitudes in support of both.[6]

One important distinction between gang involvement and violent extremism was the Somali community’s perceptions of these two types of violence. During a series of nine focus groups and in-depth interviews, ethnic Somali young adults described how the community saw radicalization to violent extremism as irrelevant.[7] Despite quantitative data suggesting some overlap in attitudes in support of gangs and violent radicalism, community perceptions of the two issues were highly divergent. Community members viewed political radicalization as an individual choice. On the other hand, these community members considered gang involvement a major community concern and the product of societal factors such as marginalization and a lack of opportunity.[8] This divergence has implications for policy and programming. Although certain risk and protective factors (for example, enhancing prosocial connections) may be common targets for different types of interventions, gang prevention programming may be more accepted by the community than programming focused on radicalization.

Terrorists and Those Involved in Human Trafficking

Research has identified two possible connections between terrorism and human trafficking. First, a terrorist organization may perpetrate human trafficking to advance its interests or meet the needs of its members; this occurs mostly in international contexts and conflict zones.[9] Second, terrorism and human trafficking may co-occur.[10]

Weine and colleagues studied an immigrant community in which terrorism and human trafficking allegedly co-occurred. The researchers conducted in-depth interviews with ethnic Somali young adults and parents, community leaders, service providers, and law enforcement officials in three U.S. cities with large Somali communities.[11] Their findings suggest that terrorism and human trafficking co-occur due to the convergence of risk (push and pull) factors.[12]

Perceived negative personal, social, cultural, economic, and political factors that pushed individuals toward these two forms of violence included:

- Poverty, lack of opportunities, unemployment, and financial hardships that made individuals vulnerable to promises of money and a better life.

- Generational divide due to parents’ lack of familiarity with the English language and American values and culture, and consequent limited ability to provide guidance and support for their children.

- High proportion of female-headed, single-parent households and dual-parent families with working parents who have limited visibility into their children’s whereabouts and thus are unable to combat negative influences or pressures to join violent groups or activities.

- Disconnect between young community members and religious leaders who represent older generations.

- Challenges associated with navigating identities of people who are Somali, Muslim, and African American.

- Unaddressed trauma and mental health problems related to integration into American society, which push youth to seek support, advice, and acceptance by misguided peers or predatory recruiters.

- Exposure to negative influences in the form of “bad company” or terrorism recruiters.

Factors that pulled individuals to both forms of violence, or that recruiters and their proxies used to depict desirable outcomes, included:

- A sense of belonging, companionship, and acceptance.

- Money or other material benefits.

- Access to the internet, where peers or recruiters used deceptive presentations of benefits.

However, some push and pull factors were limited to either terrorism or human trafficking. Distinct push factors for terrorism included:

- Political grievances against the United States and its allies.

- Perceived profiling or overpolicing by law enforcement of Somali and Black individuals and communities.

- Stereotyping and stigmatization by the media.

- Belief that the costs of joining terrorist groups are negligible.

Pull factors unique to terrorism included:

- A sense of heroism and empowerment through following extremist ideology directed at English speakers.

- Easy ways to join the cause.

Distinct push and pull factors for human trafficking, specifically alleged sex trafficking, included:

- Patriarchal beliefs about women’s lower status and submissive behavior.

- Lack of protection for women following gender role violations.

- Victims’ shame or fear of disclosing the victimization.

Taken together, negative societal responses to both human trafficking and terrorism (such as overpolicing, profiling, and media stigmatization) caused community members to perceive race- and ethnicity-based discrimination, feelings of social exclusion due to being labeled terrorists or morally inferior, and victim-blaming for not reporting victimization. Community members also lamented a lack of social services and consequently weak community efficacy, insufficient communal representation and a sense of disempowerment, distrust of government-funded programming, and perceptions that local and federal law enforcement overreact to incidents and work against the community. They were particularly concerned about cultural, social, or political stigma attached to community members who reported victimization or cooperated with law enforcement. Consequently, respondents preferred to resolve problems within the community rather than relying on those outside the community.[13]

Although these findings are drawn from one specific study and community, some of the risk and protective factors identified may have relevance for other populations, particularly those that experience social marginalization and disadvantage. The findings suggest that to prevent violent extremism, terrorism, and human trafficking, efforts must address underlying risks, disadvantages, and social problems. These include building effective prevention programs, strengthening law enforcement and community relations, increasing programmatic emphasis on community needs, and encouraging law enforcement and the media to avoid a continual focus on crime and violent extremism and terrorism in these communities.

Lone Actor Terrorists and Individuals Who Commit Nonideological Mass Murder

Targeted violence takes many forms. It can be carried out by a single person or a group. The violence can be aimed at a specific target, such as a spouse or coworkers, or it can be directed against a category of people, such as children at a school or bystanders in a public space. From the perspective of victims and survivors, the impacts may well be similar, but distinguishing the types of individuals who commit these crimes might illuminate actionable steps toward prevention.

Horgan and colleagues compared lone actor terrorists (single individuals whose terrorist acts are not directed or supported by any group or other individuals) with individuals who commit nonideological mass murder.[14] Although the motivational structure associated with each differs, the violence conducted by them appears very similar: both engage in largely public and highly publicized acts of violence, often with similar weaponry. The reasons behind any type of targeted violence are typically a “complex mix of personal, political and social drivers that crystallize at the same time to drive the individual down the path of violent action.”[15] Both lone actor terrorists and those who commit mass murder share this process.[16]

Furthermore, researchers have found little to distinguish between the sociodemographic profiles of lone actor terrorists and individuals who commit mass murder. In particular, a closer look at pre-attack behaviors revealed that both were likely to “leak” their grievances and intentions to others.[17] Although lone actor terrorists were more likely to communicate intentions or beliefs to friends and family members, others were aware of the grievances held by both groups.[18] Knowing that these individuals leak — or even deliberately broadcast[19] — their intent is important for the development of responses, particularly when there may be natural barriers to reporting this information, such as being the individual’s friend or family member.

Comparing the behavior of lone actor terrorists and individuals who commit mass murder also revealed some critical differences regarding:

- The degree to which they interact with coconspirators.

- Their antecedent event behaviors.

- The degree to which they leak information prior to the attack.

Importantly, researchers realized that they can learn more by focusing on behaviors (what people do) as opposed to focusing on characteristics (what or who people are).

For example, compared to lone actor terrorists, individuals who commit mass murder were significantly more likely to have familiarity with the attack location (79% vs. 30%). This may account for why lone actor terrorists were much more likely to engage in dry runs (34% vs. 4%). Those who committed mass murder were significantly more likely to consume drugs or alcohol just prior to the attack (20% vs. 4%). They followed a different “script” than lone actor terrorists as they moved closer to committing acts of violence; lacking an ideology, their behavior was influenced less by the prevailing social and political climate, and more by feelings of being wronged by a specific person or category of people. Overall, most individuals who committed mass murder did not pay much attention to post-attack planning or other strategic considerations. Indeed, most were either killed at the scene by police or took their own lives.[20]

Further research has compared lone actor terrorists to those who undergo radicalization in a group setting. Hamm and Spaaij found both similarities and differences between lone actor terrorists and group-based terrorists in terms of their sociodemographic profiles, behavioral patterns, and radicalization processes.[21] Compared to members of terrorist groups, lone actors were older, less educated, and more prone to mental health concerns.[22] The latter points to a potentially important mental health component in lone actor terrorism relative to group-based terrorism. Recent evidence has consistently shown that mental health concerns are more prevalent among lone actor terrorists (about 40%) than for group actors and for the general population.[23] However, the relationship between mental health and violent extremism is highly complex. Mental health is neither a reliable risk factor nor a consistent predictor of involvement in terrorism, and research to this point cannot rule out the possibility that negative mental health is a consequence rather than a potentially aggravating factor of involvement in terrorism.

Commonalities also exist between lone actor and group-based terrorists, and the boundary between these categories is often porous and fluid. Whereas group-based terrorists, by definition, exhibit a relatively high degree of interaction with coconspirators, a considerable proportion of lone actor terrorists also display an affinity with extremist groups to frame and give meaning to their beliefs and grievances. The nature and locus of such affinity with extremist groups has changed over time. Currently, it occurs primarily via online networks of like-minded activists or sympathizers found on the internet and social media platforms.[24] This insight reiterates earlier observations regarding leaking behavior: Compared to those who commit mass murder, lone actor terrorists exist in wider social networks, with varying degrees of contact with and influence from friends, family, and coworkers. Crucially, online communities often play an important role in providing a space for individuals to socialize and exchange beliefs and strategies with other extremists or sympathizers.

These studies reveal a striking and counterintuitive finding: Some terrorists, especially lone actors, leak or broadcast their intentions prior to their attacks. Knowing this, the field must develop and promote better strategies to detect and prevent such attacks. Although friends, family members, and coworkers may be well placed to detect violent ideation and intention, the fact that they know the individual creates a natural barrier to reporting. There needs to be greater effort to educate the public about the signs of attack leakage and broadcasting. Furthermore, there must be a concerted effort to provide clear, accessible, and convenient means of reporting such concerns.

Implications

The cumulative findings of these projects have implications for policy, practice, and future research. The current research highlights the various synergies and differences between violent extremism, group-based terrorism, gang activities, human trafficking, mass shootings, and lone actor terrorism. No single study provides a definitive or exhaustive set of explanations or shared risk factors. However, each provides critically important points to consider and address in future research. Moreover, the collective contribution of this body of research lies in providing a broader comparative view beyond single variables or narrow research questions. This review demonstrates that although there is no single, clear-cut overlap between the different criminal activities, they nonetheless exhibit important and sometimes unexpected similarities.

The implications extend beyond increasing knowledge, pointing toward multiple ways for policy and practice to intervene and to conduct evaluative research that addresses their impact. At the individual level, the studies suggest that although the motivational structures that underpin each type of violence vary, situationally specific combinations of push and pull factors shape individuals’ entry into, or radicalization toward, the different forms of violence. At the community level, the findings encourage policymakers and practitioners to consider effective ways to increase community awareness about the overlap in the factors that lead individuals to specific forms of violence, as well as about their potential cooccurrence, such as in the case of human trafficking associated with violent extremism and terrorism. Attention should also be directed to communal grievances that may lead community members to become alienated or engage in violent extremism, and measures should be designed to address them or lessen their impact.

The results further encourage policymakers and practitioners to embrace interventions that invest in strengthening protective measures against violence of any form. For such interventions to be accepted and endorsed by the communities in which they operate, it is important that interventions respond to community concerns, such as addressing social disadvantages that may lead to radicalization and terrorism, rather than focusing prevention efforts on the outcomes of such disadvantages. Finally, at the societal level — government, civil society, or media — promoting inclusion of those who feel they are outsiders, stigmatized, or otherwise undeserving or underserved may help reduce violence of all types.

About This Article

This article was published as part of NIJ Journal issue number 285. This article discusses the following awards:

- “Gang Affiliation and Radicalization to Violent Extremism Within Somali-American Communities,” award number 2014-ZA-BX-0001

- “Lone Wolf Terrorism in America: Using Knowledge of Radicalization Pathways To Forge Prevention Strategies,” award number 2012-ZA-BX-0001

- “A Comparative Study of Violent Extremism and Gangs,” award number 2014-ZA-BX-0002

- “Across the Universe? A Comparative Analysis of Violent Radicalization Across Three Offender Types With Implications for Criminal Justice Training Education,” award number 2013-ZA-BX-0002

- “Transnational Crimes Among Somali-Americans: Convergences of Radicalization and Trafficking,” award number 2013-ZA-BX-0008

Opinions or points of view expressed in this document represent a consensus of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position, policies, terminology, or posture of the U.S. Department of Justice on domestic violent extremism. The content is not intended to create, does not create, and may not be relied upon to create any rights, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law by any party in any matter civil or criminal.