The backbone of corrections is its workforce. The corrections sector relies on qualified, trained and dedicated staff for effective, professional operations. But today, correctional administrators, particularly those running prisons and jails, are grappling with severe workforce challenges that directly impact mission performance. Those challenges include staff recruitment, selection and retention, training and agency succession planning.

Hardly a new issue, the ongoing difficulty finding and retaining good staff has intensified to the point where many jurisdictions are now in full crisis mode.[1] For example, Kansas and West Virginia have recently issued state of emergency declarations in response to understaffed institutions.[2] Correctional officer vacancy rates in some prisons approach 50% as of late including two Mississippi institutions.[3] Although community supervision agencies typically fare better, probation and parole officer vacancy rates have been reported as high as 20%.[4] And in some state prisons, annual correctional officer turnover rates as high as 55%, test the system’s essential functionality.[5]

Given the shrinking pool of qualified workers, agencies often compete for candidates, and the sector, for a variety of reasons, appears to be losing the competition for talent.

To address the corrections workforce shortage, the RAND Corporation and the University of Denver (DU) analyzed insights from a work group of agency executives and academics who have researched the correctional workforce. This work, sponsored by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), identified a series of 64 systemic needs, with 13 top-tier needs associated with the following five themes, described in more depth below:

- Clarify the mission of the corrections sector.

- Improve staff competencies.

- Improve staff training.

- Improve work environment and conditions.

- Develop future leaders.

(See Figure 1: Top-Tier Needs)

The work group’s methods and findings, discussed below, suggest that fundamental change is needed to reverse the concerning trends of the past several years.

Nature and Scope of the Problem

Corrections is fundamentally a “people profession,” where interpersonal skills and effective face-to-face interactions are keys to effectiveness. Staff, both within institutions and in community supervision, must protect the public from individuals accused or convicted of crimes. At the same time, staff must prepare those under correctional control for successful, law-abiding lives in the community and support these individuals through the reentry process. The task facing corrections staff, then, is complex. Staff are in a unique position to have a significant impact not only on the lives and prospects of the incarcerated individuals with whom they interact, but also on the larger communities where these individuals reside or where they will return.

These complexities point to the critical importance of building a high-quality correctional workforce. However, attracting and retaining qualified corrections staff has historically been a difficult task, particularly in institutions.[6] Though for many it has proven to be a rewarding career, a variety of factors can deter individuals from entering or remaining in the field of corrections. The work is inherently dangerous, given the characteristics of the population of incarcerated individuals.[7] Beyond the risk of physical injury, there are extraordinary stressors associated with corrections work that can seriously affect the well-being of staff.[8] Beyond risk of injury and actual injury, common stressors are exposure to crisis situations and secondary trauma as well as work overload, overtime demands and role conflict. Moreover, work environments, particularly in institutional settings, can be physically harsh. For example, correctional institutions are often very noisy, many lack air conditioning and most officers work primarily indoors with little access to natural light.

Many corrections agencies operate in a paramilitary structure, which is inflexible by nature.[9] Workloads can be overwhelming because of increasing demands, limited resources and difficulties maintaining sufficient staffing levels. In institutions, mandatory overtime is common. In many states, compensation is simply not competitive with other industries and criminal justice occupations.[10] Finally, the field is challenged by the reality that the public does not consider corrections to be a high-status occupation.[11]

These internal factors have been consistent over time, but recent economic, societal and demographic changes affecting the larger workforce have exacerbated many of these challenges. For example, a record-low unemployment rate combined with a smaller labor force has created an increased competition for talent.[12] Younger employees are more willing to change jobs than their predecessors, and turnover is expensive in both dollars and loss of experience.[13] In order for the corrections sector to perform its important mission, it must critically evaluate current human resources strategies and practices and make necessary adjustments in order to compete for the best talent.

Research Purpose

The joint RAND-DU collaboration, “Building a High-Quality Correctional Workforce: Identifying the Challenges and Needs,” is part of a multiyear research effort, the Priority Criminal Justice Needs Initiative, to identify innovations in technology, policy and practice that benefit the criminal justice sector.14 In response to the significant workforce challenges discussed above, this work aimed to produce a better understanding of factors contributing to the challenges of the corrections workforce and identify key needs associated with improving outcomes such as recruitment, retention and development of high-quality staff. Findings from this work will help inform NIJ’s research agenda moving forward.

Methodology

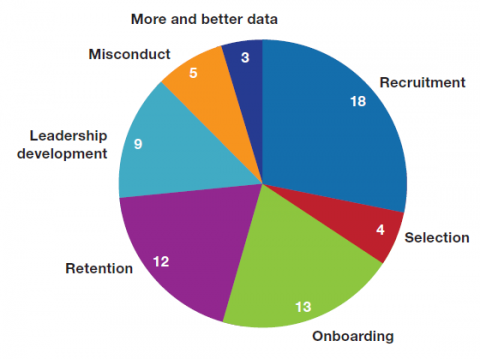

The RAND-DU team assembled a group of 13 individuals to participate in a two-day workshop. Participants included correctional agency executives, representatives of correctional associations and academics. Care was taken to include participants with experience and expertise in institutional and community corrections (or both), recognizing that each setting is unique. Before the workshop, participants were provided copies of relevant literature on the correctional workforce as a resource and discussion guide. During the workshop, RAND-DU staff conducted highly structured exercises with the group to help identify and to elicit information about the most pressing problems and to assess how these problems could be addressed. Discussions focused on several major areas relevant to a corrections staff member’s life cycle within an agency: recruitment, selection, onboarding, retention and leadership development. Issues related to staff misconduct were addressed last as it is not a distinct stage of the workforce process; rather it is a behavioral factor that can be influenced by deficiencies elsewhere in the process.

From these discussions, the research team identified a set of discrete “needs” — a term used to describe a specific area to be addressed, tied to either solving a problem or taking advantage of an opportunity for better system performance. This process yielded a total of 64 needs. (See Figure 2)

Needs and Themes

To provide structure to the large set of identified needs, participants ranked each need in terms of expected benefit (relative importance of meeting that need) and probability of success of actually meeting that need. These ratings were multiplied to produce an expected value score, and that score was used to group the needs into top, medium and low tiers.

In the final analysis, 13 of the 64 identified needs were ranked in the top tier and are listed in Figure 1. The following key themes emerged:

Clarify the mission of the corrections sector

Participants reported that the corrections sector operates in a rapidly changing environment and would benefit from a clear, cohesive and common vision for the future. This vision can help provide a road map for agencies with respect to workforce requirements tied to mission accomplishment. Overall, institutional corrections generally prioritize their custodial or surveillance objectives over their behavioral change objectives. Participants theorized that a shift in orientation might be key to reversing the long-standing difficulties the sector has faced in recruiting talent for corrections officer positions. They called for research to determine whether a shift toward an increased human-services role, along with a corresponding change in the competencies sought would help the sector attract a broader base of new talent.

Improve staff competencies in corrections environments

The corrections sector currently suffers from low levels of professionalism. This condition is most evident in corrections officers. The participants called for the reevaluation of existing, or the creation of new, competency standards for various correctional positions. These competencies should better align with the sector’s vision. With respect to probation and parole officers, greater emphasis should be placed on desired competencies (e.g., ability to deliver evidence-based interventions) as opposed to a particular level of education. Furthermore, agency processes for evaluating staff performance should be focused on these competencies.

Improve staff training

Overall, the participants articulated that the level of funding dedicated to corrections workforce training is insufficient, particularly when compared to other criminal justice professions. To quantify the impact of this disparity, participants called for an assessment of the relationships between funding levels, substandard training and key outcomes. The participants also noted that significant jurisdictional variations in the curricula (content and length) and training modalities yield uneven training across the sector. Therefore, there is a need to assess and validate the training approaches used by the sector and to develop national curriculum standards for correctional education.

Improve work environment and conditions

A number of needs were identified as essential to improving the work experience, which could positively impact recruitment and retention. Workload standards and ratios — coupled with strategies to allow agencies to meet them — are needed to ensure staff can function in a safe environment with adequate discretionary authority to fulfill their responsibilities and without undue stress. The participants noted that younger employees are most attracted to positions that allow them to actively participate in decision-making processes, particularly with respect to issues that directly affect them. The participants recognized that traditional operating structures do not mesh well with this desire; thus, they called for the development of best practices for pushing decision-making authority down to the lowest possible levels.

Develop future leaders

Leadership development is critical to all organizations, but the participants reported that the corrections sector generally does a poor job of preparing staff for supervisory and management roles. The participants called for the creation and promotion of best practices for leadership development. The participants also recommended assessments of the adequacy of training for new supervisors, the development of strategies for improvement and the compilation of best practices for leadership development. Finally, although leadership development resources exist, such as the Correctional Leadership Competencies for the 21st Century report (see Campbell et al., 2006), there is a need for publishers to review and revise these documents in order to maintain their relevance.

Shifting the paradigm

Many correctional agencies are facing a workforce crisis. They struggle to recruit, retain and develop high-quality staff. Although there was consensus among the participants that improved compensation is necessary, this is only a partial solution. Moreover, decisions requiring new resources are essentially beyond an agency’s direct control. Therefore, emphasis should be placed on the needs that these agencies, and the sector as a whole, can influence.

Many of the top-tier needs identified in the RAND-DU report support an argument for a paradigm shift on many levels. For example, the participants argued that a shift in orientation from a punitive/surveillance model to more of a human-services model may attract recruits in larger numbers, mitigating vacancy issues. Such a model may also result in more manageable workloads, a less stressful work environment, and ultimately, better outcomes of incarcerated individuals, which can all help mitigate turnover issues. Although some agencies are beginning to reap benefits from such a shift, empirical data is needed to support the case for widespread change.

According to the participants, as this shift essentially redefines the role of many staff, recruitment and selection strategies will need to change accordingly. Further, changes will be needed to attract younger employees to corrections staff. Additionally, the paramilitary structure of corrections should be reexamined. Where possible, staff should be offered more flexibility as well as input into decisions that affect their work experience.

Finally, the participants argued that in order to build a high-quality workforce, there must be sustained investments in training, nurturing and developing staff with an emphasis on grooming future leaders.

| Problem or Opportunity | Need |

|---|---|

| The role of corrections staff, particularly in institutions, is generally viewed to be custodial or surveillance-oriented, which limits the sector's ability to attract new talent.

|

Research the implications that a human-services approach and culture would have on recruitment.

|

| Increasingly, new generations of employees have expectations that they will be able to actively participate in policy and decision-making.

|

Develop best-practices for pushing decision-making authority down to the lowest level.

|

| The general level of professionalism in the correctional workforce is relatively low, particularly among corrections officers.

|

Reevaluate or create competency standards for various correctional positions.

|

| The sector lacks a coherent vision. Because agencies operate in a rapidly shifting environment, they are struggling to keep pace both in general and with respect to their workforces in particular.

|

Develop a national vision and strategy for corrections, similar to those developed for other criminal justice sectors.

|

| Funding levels dedicated to educating and training the correctional workforce that lag behind those for other comparable fields, most notably law enforcement.

|

Assess the impact of inadequate training funding on the sector's ability to accomplish its mission.

|

| There is significant variation in the curricula and approaches agencies use to train and educate the correctional workforce, as well as the duration of preparation before assignment.

|

Develop minimum national standards for correctional professional education and training including curriculum and training hours.

|

| Training is often impractical and unrealistic, and there is incongruity between how officers are trained and what they will experience on the job.

|

Assess and validate the evidence behind the various training methods and curricula in use, as well as the timing of delivery.

|

| After dedicating significant resources to recruit and train staff, agencies often fail to recognize the value of retaining them.

|

Promote evidence-based best practices proven to improve job satisfaction, engagement and other factors related to low turnover intention.

|

| Excessive workloads and high incarcerated individual-to-officer ratios are related to a variety of negative outcomes and can hinder an organization's ability to retain staff.

|

Assess and validate existing standards for staffing ratios and examine such strategies as capped caseloads to allow agencies to meet these standards.

|

| Correctional agencies do not place sufficient emphasis on leadership and management training.

|

Evaluate and promote best practices for leadership development within the sector.

|

| Existing resources that support leadership development are often out-of-date.

|

Reevaluate and update these resources as necessary.

|

| The staff evaluation processes used by most agencies do not focus on the most important competencies.

|

Examine the most appropriate performance measures by which to evaluate each position.

|

| Line and mid-level supervisors lack the skills needed to mentor new hires effectively.

|

Assess the adequacy of training for new supervisors and develop strategies for improvement.

|