Young adults with a history of maltreatment and foster care placement are at significant risk for dating violence perpetration and victimization. [1-4] In a study funded by NIJ, researchers examined the relationship between pre-adolescent risk factors and dating violence in young adulthood. The researchers also looked at other factors throughout mid-adolescence and young adulthood that may serve as a “link” between these pre-adolescent risk factors and later dating violence.

The study recruited a total of 215 young adults between the ages of 18-22 who had previously been enrolled in the Fostering Healthy Futures program. The Fostering Healthy Futures program is a Positive Youth Development (PYD) program for maltreated youth and initially enrolled all 9- to 11-year olds placed in out-of-home care within the previous year in the Denver metro area.[5]

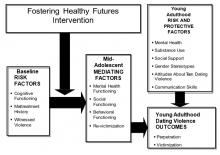

Researchers obtained baseline pre-adolescent risk factors from child welfare, court records, and interviews with children and their caregivers. The youth were then re-interviewed throughout mid-adolescence (1.5 years post-enrollment and 2.5-3.5 years post-enrollment) and again in young adulthood (9.4 years post-enrollment). The overall model is shown in Figure 1.

The findings from the study found that the majority of participants who were victims of maltreatment as adolescents had perpetrated or been victimized by dating violence in the past year. The most common form of dating violence was emotional or verbal abuse, and the least common was sexual violence, which is consistent with past research.

In general, pre-adolescent risk factors did not predict dating violence in young adulthood. However, a caregiver exposing or involving the child in illegal activity or other activities that may foster delinquency or antisocial behavior is a consistent predictor of a higher likelihood that those adolescents would later become victims of dating violence. The researchers found no correlation between pre-adolescent risk factors and teen dating violence perpetration.

Baseline pre-adolescent risk factors taken all together as a group were related to trauma symptoms, externalizing problems, and decreased caregiver attachment in mid-adolescence. Specifically, caregivers exposing or involving pre-adolescence in illegal activity was associated with the child being less attached to the caregiver attachment in mid-adolescence, highlighting this potentially important form of maltreatment in the pathway to violence.

Risk and protective factors in mid-adolescence were all related to dating violence victimization and perpetration in young adulthood six years later. Specifically, having trauma symptoms, externalizing problems, or being re-victimized during adolescence was associated with increased dating violence. On the other hand, caregiver attachment during adolescence was related to decreases in dating violence.

Risk and protective factors in young adulthood were the most strongly associated with dating violence, as may be expected because of time proximity. Specifically, trauma symptoms, substance use, and dating violence attitudes and behaviors were related to increases in dating violence outcomes. Higher current social support was associated with less dating violence.

Overall, the study indicated that youth in foster care with a history of early maltreatment are at high risk for experiencing dating violence in young adulthood, and that certain risk and protective factors across the developmental trajectory play important roles. Given the strong association between adolescent and young adult risk factors in predicting dating violence, targeting certain processes during the adolescent and young adult years may be particularly useful time points for devising and implementing intervention and prevention strategies.

It is important to note that the Fostering Healthy Futures intervention did not seem to protect against the negative impact of pre-adolescent risk factors on dating violence in young adulthood, although it did have important effects on other important outcomes (e.g., mental health, placement stability, and permanence).[6]

About This Article

The research described in the article was funded by NIJ award 2013-VA-CX-0002, awarded to the University of Colorado, Denver. This article is based on the grant summary “Long-Term Impact of a Positive Youth Development Program on Dating Violence Outcomes During the Transition to Adulthood” (pdf, 14 pages) by Heather Taussig, Ph.D., and Edward Garrido, Ph.D.

This research is part of a broader portfolio of intimate partner violence projects. Learn more about NIJ’s intimate partner violence research portfolio.