Bruises are one of the most common injuries observed on victims of violent crime, such as victims of sexual assault and domestic violence [1, 2]. In 2019, over 5.8 million individuals were victims of a violent crime in the United States, with nearly 460,000 rape or sexual assaults, and over 1.1 million instances of domestic and intimate partner violence [3]. However, bruises can be difficult for forensic nurse examiners to detect, particularly on victims with darker skin tones. An inaccurate documentation of injuries can be detrimental to the victim’s legal case against their attacker as well as to the victim’s medical treatment. Researcher Katherine Scafide, Ph.D., a former forensic nurse examiner and now an assistant professor at George Mason University, and her colleagues are investigating the use of alternate light sources to more accurately detect bruising across all skin tones [4].

During Scafide’s eight years as a forensic nurse examiner, one particular case stands out in her mind. As Scafide was examining the victim, documenting injuries and collecting evidence, the victim exclaimed that the individual bit her on her back. Scafide thought, if I can locate this bite – this bruise – I can swab for DNA evidence. She looked for the bruise using all the tools she had available at the time but could not locate the bite or corresponding bruise on the woman’s dark skin. Without documentation, there was nothing to substantiate the victim’s claim, and when their injuries cannot be documented, women are less likely to report incidents of sexual assault, are less likely to engage in the process, and have worse judicial and medical outcomes. This case inspired Scafide to look to technology to address the challenge of finding effective ways to discover bruise injuries regardless of the underlying skin color.[5]

Characterizing Bruise Injuries

Scafide’s dissertation research focused on the relationship between skin color, sex, and subcutaneous fat in bruises over time. She used a colorimeter, a tool used to gauge the color of objects, to document bruising color changes over time across a broad range of skin colors. It was during this time that Scafide was coined the “Paintball Lady” – a nickname still held to this day. Scafide needed a method to ethically create consistent bruises. The bruises served as controls, where the size, shape, and force applied were consistent; and time and location of injury was known. After reviewing the literature, she came across some researchers that used a paintball gun to achieve consistent, reproducible superficial bruises. Since many people already engage in paintball as a sport and enjoy it, Scafide employed this technique on volunteers during her dissertation research and has continued to employ this method in subsequent NIJ-funded research [6].

Randomized Controlled Trial: White Light Vs. Alternate Light Source

Since her time as a forensic nurse examiner, Scafide has been interested in using technology to remove any subjectivity from injury documentation. Specifically, she wanted to overcome the challenge of detecting bruises across all skin tones. During her training, she had heard of using an alternate light source to better visualize bruises and discovered a recommendation from the 2013 Department of Justice’s Office of Violence Against Women report to use an alternate light source for visualization of trace evidence, biological fluids, and subtle injury.[7, 8]

See the sidebar "Alternate Light Source Technology."

The body of research in this area was small, thus Scafide saw an “opportunity to solve a clinical problem through rigorous research.” Scafide collaborated with Daniel Sheridan, Ph.D., at Texas A&M University College of Nursing to design a research methodology incorporating randomized controlled trials to assess bruise visibility on a very diverse sample of skin colors.[9] Scafide and Sheridan submitted this research design as a competitive proposal to NIJ’s Research and Development in Forensic Sciences for Criminal Justice Purposes program, and received a grant award in 2016 “Analysis of Alternative Light in the Detection and Visibility of Cutaneous Bruises”.

With support from the 2016 award, Scafide and her team investigated whether or not an alternate light source, a tool that provides light of a specific wavelength [10], is more useful for detecting and visualizing bruises than standard white light. Furthermore, they wanted to investigate what variables – in either the individual (skin color, sex, age, and ratio of subcutaneous fat to muscle) or the bruise (age of bruise and size of bruise) – affected an examiner’s ability to detect the bruise. [11]

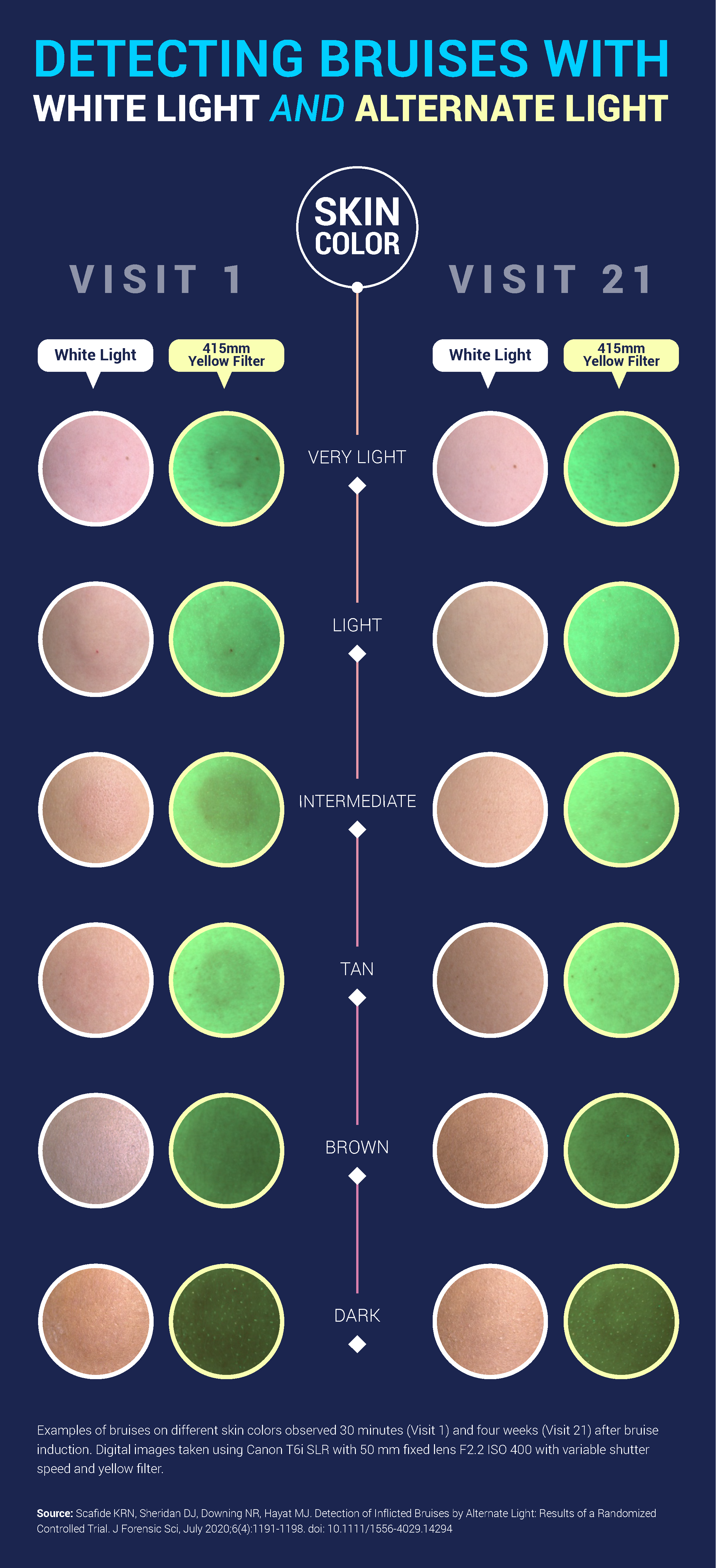

Scafide again used a paintball gun to create consistent bruises on the volunteer test subjects. For this study, the researchers mounted a paintball gun on a stand and affixed it with a laser sight for accuracy. Subjects stood behind a full coverage wooden apparatus with a hole exposing only the upper arm. The sample size for the randomized controlled trial included 157 individuals divided across six skin color categories (as calculated by the individual typology angle colormetric classification [12]). The researchers documented evidence of bruising using either an alternate light source or white light (randomized) through 21 visits over four weeks after initial bruising. The order of which light source was used first was randomized throughout the assessment period. [13]

The research team reported that they were five times more likely to detect a bruise on study participants with an alternate light source than with white light. More specifically, alternate light at 415 and 450 nanometer wavelengths with a yellow filter resulted in the greatest bruise detection [14], regardless of skin color. Scafide was surprised by these results, initially expecting that when it comes to darker skin, higher wavelengths would have been more effective in visualizing bruising because melanin (a major determinant of darker skin tones) absorbs light across all wavelengths, however, the amount of absorption decreases with increasing wavelengths.[15]

With this study, “we wanted to pinpoint what is the best bang for the buck,” said Scafide “This is a significant finding and of great value to law enforcement and clinical forensic units with meager budgets.”[16]

Taking Alternate Light from Theory to Practice

Scafide’s passion for bruise detection and visibility continued after she became an assistant professor. After her initial NIJ-supported project ended with promising results in a laboratory setting, it was time for her to translate the research into practice. In 2019, Scafide was awarded a second competitive NIJ grant to support this effort after applying to the Research and Evaluation on Violence Against Women: Sexual Violence, Intimate Partner Violence, Stalking, and Teen Dating Violencefunding opportunity.

The project, “Improving the Forensic Documentation of Injuries through Alternate Light: A Researcher-Practitioner Partnership,” seeks to assess and evaluate the implementation of alternate light sources in forensic nursing units. Scafide explains that there are a lot of forensic units that still are cautious about using alternate light source technology for bruise detection. One nurse explained to Scafide that they have grant money to buy alternate light source equipment, but they do not know how to use it. Scafide hopes to quell these concerns and offer evidence-based implementation strategies and protocols for forensic nursing units that are widely applicable across agencies and usable across diverse populations. [17]

In addition to informing the forensic practitioner community with evidence-based protocols and implementation strategies, Scafide is also interested in the potential impact of alternate light source in bruise detection on law enforcement decision making, legal outcomes, and court decision making. She has assembled a diverse team to evaluate the feasibility of using ALS in bruise detection from not only the forensic nursing practitioner perspective but also law enforcement and legal perspectives. [18]

Scafide stated “I think there is tremendous potential for this technology to improve patient care amongst diverse victims, however we need to implement it in an evidence-based manner. And so the next step from doing research is to translate that research into practice and evaluate it. And so that’s the important next step of our project.”[19]

Alternate Light Source Technology

An alternate light source can be used to identify physiological evidence, including bruises, biological fluids, and hair, and physical evidence, such as fibers and other trace materials, through fluorescence by using specific wavelengths of light.