Policing strategies and practices increasingly incorporate geographic information systems (GIS) with advanced data analytics. For example, the practice of hot spots policing uses this technology to identify small geographic areas within a jurisdiction where crime has concentrated, allowing police agencies to better focus their limited resources. More recently, sophisticated analytical techniques have been applied to forecast crime. These forecasts may focus on place (where crime occurs) or on persons (individuals involved in a crime as those committing it, victims, or witnesses). Together with relevant interventions, this practice has been termed predictive policing.

Learn more about studies of hot spot policing on CrimeSolutions.

In 2012, as part of the second phase of a larger NIJ-funded project to study predictive policing, the Shreveport (Louisiana) Police Department (SPD) compared a predictive policing model focused on forecasting the likelihood of property crime occurring within block-sized areas, against a hot spots policing approach in a randomized, controlled experiment.

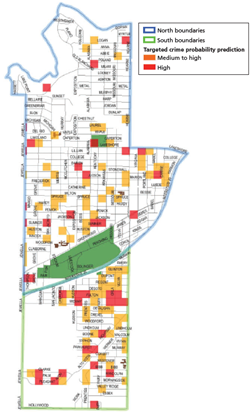

SPD identified six districts with the highest levels of property crime in its jurisdiction and randomly selected three of them to implement the predictive policing approach that SPD had developed. The other three districts continued to use their existing hot spots-based approach. All of the districts received additional funding for overtime work to conduct special operations in targeted areas.

Both the experimental and control districts employed interventions that involved the use of special operations to target property crime. The predictive policing approach targeted special operations to locations where property crime was forecast to occur. The hot spots approach targeted special operations to locations where clusters of property crimes had already occurred.

Researchers from RAND conducted an evaluation of the program. At the end of the study, they found no significant differences in levels of property crime between the two groups.

The evaluation also looked at how the three experimental districts implemented the predictive policing program. The researchers examined both the implementation of the forecast model (generating and mapping future property-crime locations) and the implementation of the intervention model (targeting the locations identified by the forecast model for special operations).

How closely agencies stick to a program model — the fidelity of implementation — is a critical issue in evaluation. When agencies do not carry out programs as designed, researchers have no way to know if changes (or lack of changes) they observe are due to the program.

The researchers found that the three experimental districts adhered closely to the forecast model as originally envisioned for generating and mapping forecasts of future property-crime locations on a weekly basis. One change made by the agency during the study was to add more information that indicated community disorder to their maps to help inform daily decisions. This information included recent crimes, 911 calls, field interviews, and recently targeted hot spots.

The experimental districts, however, diverged from the prevention model in two important ways. First, the level of effort agencies expended on targeted prevention was inconsistent. For the first four months of the experiment, two of the experimental districts (which were under a single command) saw an average 35-percent reduction in property crime. For those four months, the experimental group — driven by the drop in crime in two of the three experimental districts — had significantly less property crime than the control group. However, the effort expended by those two districts declined over the last three months of the study, and the level of crime rose again to the level in the control districts.

Second, the experimental districts implemented the intervention model differently and did not hold regular meetings with each other as called for by the model to coordinate their interventions. The fact that there was no significant change in crime in the third experimental district during the study, in contrast to the two other experimental districts during the first four months, could be related to the differences in strategies the districts used.

The researchers point to implementation failures, low statistical power, and problems with the underlying theory of the program as potential explanations for the lack of difference in property crime levels between the two groups. In addition, they note the possibility that the forecasts themselves simply do not add enough new information over the conventional hot spots method to make a difference in policing activity.

Based on this study, it is difficult to draw conclusions about how effective the practice of predictive policing is relative to hot spots policing, or whether changing to a predictive policing approach would have a benefit for police agencies based on this study.

In their final report, the researchers discuss the need for further research and more definitive assessments. They lay out several elements that future research on predictive policing should consider, including:

- Increasing statistical power by ensuring that both groups use the same interventions and levels of effort.

- Testing the differences between forecast maps and hot spots maps to find out what practical differences exist in terms of where officers patrol.

- Considering how forecast models and maps might change when treatment is applied — criminal response to interventions could change the accuracy of forecasts.

- Checking on how interventions are implemented to ensure fidelity.

About This Article

The work discussed in this article was completed under grant number 2009-IJ-CX-K114 awarded by NIJ to RAND. The grant report Evaluation of the Shreveport Predictive Policing Experiment (pdf, 89 pages) by Priscilla Hunt, Jessica Saunders, and John S. Hollywood was the bases for this article.