According to the National Fire Protection Association, approximately 261,000 fires were intentionally set each year from 2010 to 2014 in the United States, with a resulting annual death rate of about 440 people. Determining whether a fire was arson is a daunting problem for investigators. Ascertaining the origin and course of a fire are important first steps in reconstructing the scene of a possible crime.

In a study supported by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), Underwriters Laboratories (UL) noted that the “lack of knowledge of post-flashover and ventilation-controlled fire damage by fire investigators has resulted in unwarranted prosecutions and incarcerations for arson.” The role of ventilation in a fire, such as an open door or window, changes the fire patterns investigators examine and, according to the UL researchers, “In past criminal cases, fire investigators have misunderstood ventilation generated patterns and incorrectly identified them as evidence of arson.”

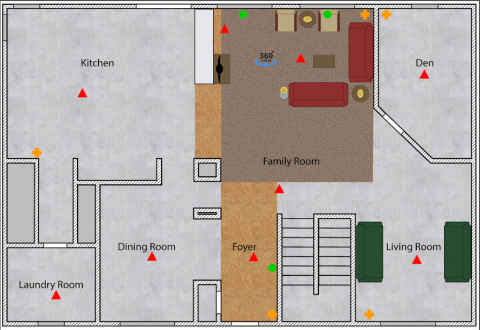

To provide more valid scientific data to fire investigators, UL researchers conducted a series of experiments on fires with and without ventilation, and in a secondary study they looked at how energized electrical cords fail when fires progress. The scientists built three types of test structures: a single-story ranch house, a two-story colonial house, and a smaller one-room compartment.

In the larger structures, the scientists conducted heat release rate experiments on sofas, chairs, and beds used as fuel loads to ensure that flashover conditions could be attained. Flashover occurs when the majority of exposed material in a space reaches its “autoignition” temperature and emits flammable gas. Flashover typically occurs at temperatures above 900 degrees Fahrenheit.

In several experiments with the ranch and colonial houses, the researchers found that increasing the ventilation available to the fire resulted in additional burn time, additional fire growth, and a larger area of fire damage within the structures. “Fire patterns within the room of origin led to the area of origin [of the fire] when the ventilation of the structure was considered. Fire patterns generated pre-flashover persisted post-flashover if the ventilation points were remote from the area of origin.”

The study provided “foundational documentation for the understanding of ventilation-controlled fires and the resulting fire patterns,” the scientists said. This is important in the “understanding of separate and distinct fire patterns that are generated by ventilation-controlled burning conditions in a building.” They noted that the changes in burn patterns documented in the study were “consistent with fire dynamics-based assessments and were repeatable.”

The study of electrical cords showed that despite the variety of six types of cords tested, they all eventually lost their insulation and tripped their power circuits as the fire burned. The cord experiments document that “when the energized cable’s insulation burns away to the point that a short circuit or ground fault occurs, the physical damage was similar among the different cable types regardless of the type of electrical circuit protections.”

About This Article

The research described in this article was funded by NIJ grant 2015-DN-BX-K052, awarded to Underwriters Laboratories, Northbrook, Illinois. The article is based on the grantee report “Study of the Impact of Ventilation on Fire Patterns and Electrical System Damage in Single Family Homes Incorporating Modern Construction Practices,” by Daniel Madrzykowski.