When I speak to police officers about my research on sleep, job performance and shift work, they always ask, "What's the best shift?"

I always answer, "That's the wrong question. Most shift arrangements have good and bad aspects." The right question is this: "What is the best way to manage shift work, keep our officers healthy and maintain high performance in our organization?"

Scheduling and staffing around the clock requires finding a way to balance each organization's unique needs with those of its officers. Questions like "How many hours in a row should officers work?" and "How many officers are needed on which shift?" need to be balanced against "How much time off do officers need to rest and recuperate properly?" and "What's the best way to schedule those hours to keep employees safe and performing well?"

After all, shift work interferes with normal sleep and forces people to work at unnatural times of the day when their bodies are programmed to sleep. Sleep-loss-related fatigue degrades performance, productivity and safety as well as health and well-being. Fatigue costs the U.S. economy $136 billion per year in health-related lost productivity alone.[1]

In the last decade, many managers in policing and corrections have begun to acknowledge — like their counterparts in other industries — that rotating shift work is inherently dangerous, especially when one works the graveyard shift. Managers in aviation, railroading and trucking, for example, have had mandated hours-of-work laws for decades. And more recently they have begun to use complex mathematical models to manage fatigue-related risks.[2]

All of us experience the everyday stress associated with family life, health and finances. Most of us also feel work-related stress associated with bad supervisors, long commutes, inadequate equipment and difficult assignments. But police and corrections officers also must deal with the stresses of working shifts, witnessing or experiencing trauma, and managing dangerous confrontations.

My colleague, John Violanti, Ph.D., a 23-year veteran of the New York State Police, is currently a professor in the Department of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University at Buffalo and an instructor with the Law Enforcement Wellness Association. His research shows that law enforcement officers are dying earlier than they should. The average age of death for police officers in his 40-year study was 66 years of age — a full 10 years sooner than the norm.[3]

He and other researchers also found that police officers were much more likely than the general public to have higher-than-recommended cholesterol levels, higher-than-average pulse rates and diastolic blood pressure,[4] and much higher prevalence of sleep disorders.[5]

So what can we do to make police work healthier? Many things. One of the most effective strategies is to get enough sleep. It sounds simple, but it is not. More than half of police officers fail to get adequate rest, and they have 44 percent higher levels of obstructive sleep apnea than the general public.

More than 90 percent report being routinely fatigued, and 85 percent report driving while drowsy.[6]

Sleep deprivation is dangerous. Researchers have shown that being awake for 19 hours produces impairments that are comparable to having a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of .05 percent. Being awake for 24 hours is comparable to having a BAC of roughly .10 percent.[7] This means that in just five hours — the difference between going without sleep for 19 hours versus 24 hours — the impact essentially doubles. (It should be noted that, in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, it is a crime to drive with a BAC of .08 percent or above.)

If you work a 10-hour shift, then attend court, then pick up your kids from school, drive home (hoping you do not fall asleep at the wheel), catch a couple hours of sleep, then get up and go back to work — and you do this for a week — you may be driving your patrol car while just as impaired as the last person you arrested for DUI.

Bars and taverns are legally liable for serving too many drinks to people who then drive, have an accident and kill someone. There is recent precedent for trucking companies and other employers being held responsible for drivers who cause accidents after working longer than permitted. It seems very likely that police departments eventually will be held responsible if an officer causes a death because he was too tired to drive home safely.

Sleep and fatigue are basic survival issues, just like patrol tactics, firearms safety and pursuit driving. To reduce risks, stay alive and keep healthy, officers and their managers have to work together to manage fatigue. Too-tired cops put themselves, their fellow officers and the communities they serve at risk.

Accidental Deaths and Fatigue

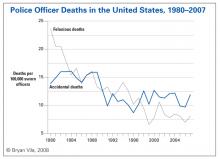

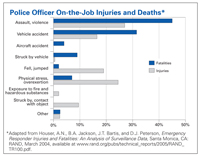

The number of police officer deaths from both felonious assaults and accidents has decreased in recent years. Contrary to what most people might think, however, more officers die as a result of accidents than criminal assaults. Ninety-one percent of accidental deaths are caused by car crashes, being hit by vehicles while on foot, aircraft accidents, falls or jumping.

We know that the rate of these accidents increases with lack of sleep and time of day. Researchers have shown that the risk increases considerably after a person has been on duty nine hours or more. After 10 hours on duty, the risk increases by approximately 90 percent; after 12 hours, 110 percent.[8] The night shift has the greatest risk for accidents; they are almost three times more likely to happen during the night shift than the morning shift.

Countering Fatigue

Researchers who study officer stress, sleep and performance have a number of techniques to counteract sleep deprivation and stress. They fall into two types:

- Things managers can do.

- Things officers can do.

The practices listed below have been well-received by departments that recognize that a tired cop is a danger both to himself and to the public.

Things Managers Can Do

- Review policies that affect overtime, moonlighting and the number of consecutive hours a person can work. Make sure the policies keep shift rotation to a minimum and give officers adequate rest time. The Albuquerque (N.M.) Police Department, for example, prohibits officers from working more than 16 hours a day and limits overtime to 20 hours per week. This practice earned the Albuquerque team the Healthy Sleep Capital award from the National Sleep Foundation.

- Give officers a voice in decisions related to their work hours and shift scheduling. People's work hours affect every aspect of their lives. Increasing the amount of control and predictability in one's life improves a host of psychological and physical characteristics, including job satisfaction.

- Formally assess the level of fatigue officers experience, the quality of their sleep and how tired they are while on the job, as well as their attitudes toward fatigue and work hours issues. Strategies include: administering sleep quality tests like those available on the National Sleep Foundation's Web site (www.sleepfoundation.org, and training supervisors to be alert for signs that officers are overly tired (for example, falling asleep during a watch briefing) and on how to deal with those who are too fatigued to work safely.

Several Canadian police departments are including sleep screening in officers' annual assessments — something that every department should consider.

- Create a culture in which officers receive adequate information about the importance of good sleep habits, the hazards associated with fatigue and shift work, and strategies for managing them. For example, the Seattle Police Department has scheduled an all-day fatigue countermeasures training course for every sergeant, lieutenant and captain. In the Calgary Police Service, management and union leaders are conducting a long-term, research-based program to find the best shift and scheduling arrangements and to change cultural attitudes about sleep and fatigue.

Things Officers Can Do

- Stay physically fit: Get enough exercise, maintain a healthy body weight, eat several fruits and vegetables a day, and stop smoking.

- Learn to use caffeine effectively by restricting routine intake to the equivalent of one or two eight-ounce cups of coffee a day. When you need to combat drowsiness, drink only one cup every hour or two; stop doses well before bedtime.[9]

- Exercise proper sleep hygiene. In other words, do everything possible to get seven or more hours of sleep every day. For example, go to sleep at the same time every day as much as possible; avoid alcohol just before bedtime; use room darkening curtains; make your bedroom a place for sleep, not for doing work or watching TV. Do not just doze off in an easy chair or on the sofa with the television on.

- If you have not been able to get enough sleep, try to take a nap before your shift. Done properly, a 20-minute catnap is proven to improve performance, elevate mood and increase creativity.

- If you are frequently fatigued, drowsy, snore or have a large build, ask your doctor to check you for sleep apnea. Because many physicians have little training in sleep issues, it is a good idea to see someone who specializes in sleep medicine.

About This Article

This article appeared in NIJ Journal Issue 262, March 2009.