The 2023 NIJ National Research Conference lived up to its theme of “Evidence to Action.” The event proved to be a magnet for researchers and justice agency professionals who rely on scientific advances to shape effective policy and practice solutions to crime.

After a hiatus of 11 years, the rebirth of the NIJ research conference featured plenary sessions on overarching issues for the field as well as expert panels detailing vital new research findings.

One series of presentations focused on the prevalence of correctional officer stress, its debilitating effects, and ways to address it. This article summarizes key insights from those presentations.

Examining and mitigating correctional officer workplace stressors

Speakers at the session on correctional officer stress included:

- Rhianna Kohl, Ph.D., executive director, Office of Strategic Planning & Research, Massachusetts Department of Correction.

- Natasha A. Frost, Ph.D., professor and associate dean, Northeastern University.

- Joseph A. Schwartz, Ph.D., associate professor, Florida State University.

- Diane Elliot, MD, FACP, FACSM, professor, Oregon Health & Science University and Oregon Health Workforce Center.

Correctional officer stress stems from two primary sources:

- The demands of responding to critical incidents within the correctional facility.

- More mundane organizational stressors, ranging from understaffed shifts to toxic work environments.

Panelists in the conference session on “Examining and Mitigating Correctional Officer Workplace Stressors” discussed the effects and interactions of both sources of stress, as well as promising mitigation strategies.

Signs of correctional officer stress

Panelist Natasha A. Frost has led NIJ-funded research to investigate correctional officer well-being, officer suicidality, and the effects of officer suicide on colleagues. Frost and her team at Northeastern University initiated this research in response to an unusually high number of Massachusetts Department of Correction (MADOC) corrections officers dying by suicide between 2010 and 2015.

Frost’s research found that about 25% of correctional officers in the study self-reported symptoms consistent with at least one psychological distress outcome. The average suicide rate for MADOC corrections officers over this period was approximately 105 per 100,000 — at least seven times higher than the national suicide rate (14 per 100,000), and almost 12 times higher than the suicide rate for the state of Massachusetts (nine per 100,000). Frost’s account of this study appeared in Corrections Today in 2020 (see “Understanding the Impacts of Corrections Officer Suicide”).

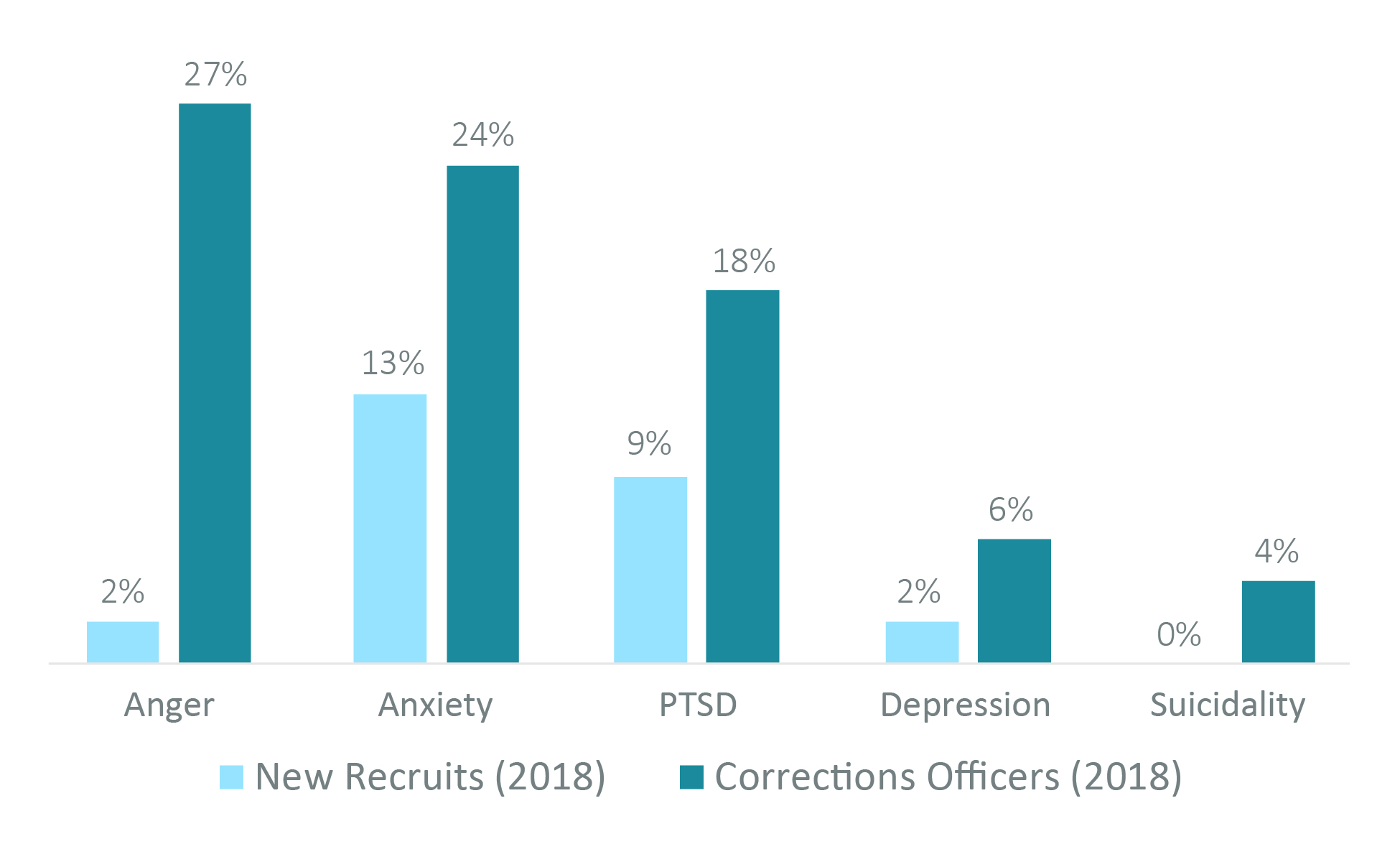

Five percent of all Massachusetts correctional officers exhibited signs of suicidality, 20% had symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and 25% had symptoms of anger and anxiety.1 Additionally, officers had a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing distress, including suicidality, if they had known another officer who died by suicide.

The study found that departmental discipline, job satisfaction, and strain-based work-family conflict were all significant correlates of compromised mental health among corrections officers.

It is possible, in light of these findings, that stress builds during one’s tenure on the job, impacting the health and well-being of corrections officers. Notably, among new officer recruits, the research team found little evidence of compromised psychological functioning. But the findings were not conclusive.

Figure1: Symptoms of Psychological Distress

Frost’s initial policy implications from this research recommended that corrections agencies should:

- Proactively address officer health and wellness.

- Provide critical incident aftercare.

- Attend to organizational and occupational stressors.

- Destigmatize mental health conditions.

- Address aspects of correctional culture that stigmatize help-seeking.

Presenting on the first longitudinal study of corrections officer stress

In response to this finding, the Northeastern team is conducting the first long-term study of occupational stress, violence exposures, and psychological distress for a cohort of correctional officers. Officers taking part in the study graduated from the basic training course of the Massachusetts Department of Correction (MADOC) between 2020 and 2023.

The study phase currently underway examines the short- and long-term impacts of chronic operational and organizational stressors related to exposure to violent and traumatic incidents. The research seeks to identify causal relationships for a more comprehensive understanding of the risk factors for clinically elevated symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, and suicidal ideation. These factors can all be precursors to suicide among correctional officers.

The researchers initially conducted approximately 250 interviews of new correctional officers who completed MADOC’s basic training course from 2020 through the end of July 2023. Key early findings, summarized in Frost’s panel presentation, include:

- Recruit Diversity: The incoming correctional facility workforce was predominately male (76%) and white (63%); however, it was significantly more diverse than the incumbent workforce.

- The Academy Experience: The academy program perpetuated a hypermasculine correctional culture with its emphasison self-reliance, aggression, toughness, independence, and suppression of any appearance of weakness.

- Retention Prospects: Results from the first interviews found that 76% of respondents indicated that corrections was likely to be their long-term career, 12% had already thought about quitting, and 10% had left the department within their first year.

When interviewed after the conference session, Frost elaborated on two primary reasons that the mental health of officers has received insufficient attention:

- Officer concern that addressing their mental health issues would have negative repercussions at work.

- Societal stigmatization of mental health issues.

Frost explained, “Officers fear repercussions at work, for instance in their fitness-for-duty evaluations. They are reluctant to disclose mental health issues and to seek help when they are struggling. This has broader implications for both the workforce and for the incarcerated population.”

Frost noted there are signs that the stigma of acknowledging and addressing mental health issues is fading as many in the correctional field redouble their focus on officer health and wellness. “A focus on officers, on officer mental health, and the ways in which they are impacted by their work environments is long overdue,” she said. “Thankfully, some of those conversations have now started, and officer health and wellness is becoming a priority of correction agencies across the country. I am optimistic that a focus on the issues officers have long faced — but too frequently felt they had to hide — will begin to shift the narrative.”

A link between critical incidents and mental health problems

Given the important role that exposure to trauma can play in officer wellness documented by Frost, it is essential that the types of incidents that induce trauma or better understood. Dr. Schwartz of Florida State University presented at the conference on how certain physiological and psychological responses to critical prison incidents can lead to the development of mental health problems among correctional officers.[2]

Schwartz and his colleagues found that:[3]

- Mental health problems were highly prevalent among correctional officers.

- There was a correlation between greater critical incident exposure and increased mental health symptoms

- The mental health symptoms likely would not occur in the absence of psychological stress.

- There was no detectable significant relationship between exposure to psychological stress and elevated biomarkers (the human hormone cortisol and the enzyme alpha-amylase, which can indicate the presence of stress.) That means those measures of stress are not consistently reliable, at least in this study.

Further, their research suggests that changes in psychological stress following critical incident exposure are a primary mechanism connecting work-related critical incident exposure and mental health problems among correctional officers. These findings could be critical for intervention and prevention strategies.

Schwartz and his team recommended the following steps to improve corrections officer resilience and well-being:

- Adopt initiatives targeting change.

- Involve the entire agency.

- Address multiple domains of wellness.

- Initiate modeling of good behavior.

- Provide routine health and wellness checks.

- Create systems to track change.

- Develop officer safety and wellness toolkits.

The panel also covered findings from research on the impact of stressors on correctional officer well-being. In one study, panelist Diane Elliot, MD, FACP, FASCM, professor, Oregon Health & Science University and the Oregon Health Workforce Center, and her colleagues found that:

- Stress increases with:

- Increased work hours.

- Work-related demands.

- Operational stressors.

- Stress does not increase with:

- Changes in the public image of correctional officers.

- Supervisor/co-worker support.

- Witnessed/experienced violence.

Another study examined MRI scans of officers’ brains, finding that high stress activates parts of the brain involved in sustaining attention and ignoring distracting information. This suggests that, in highly demanding circumstances, those officers may be unable to inhibit inappropriate or automatic responses.[4]

Mindfulness training shows promise in relieving officer stress

During another NIJ conference session, panelists described mindfulness training developed to support officers exposed to high levels of stress.[5] Prolonged stress can cause burnout, characterized by symptoms of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of low personal accomplishment. Mindfulness training is one promising solution to these stress -related outcomes. Speakers included:

- Daniel Grupe, Ph.D., associate scientist, Center for Healthy Minds, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Michael Christopher, professor, Pacific University.

- Heather Rusch, National Institutes of Mental Health.

- Diane Elliot, MD, FACP, FACSM, professor, Oregon Health & Science University and Oregon Health Workforce Center.

According to a report on mindfulness training for law enforcement officers by panelist Daniel Grupe, mindfulness is the practice of intentionally bringing awareness to present-moment experiences — thoughts, sensations, emotions — with a spirit of openness and acceptance.[6] Expressed differently, “Mindfulness is a type of meditation in which you focus on being intensely aware of what you’re sensing and feeling in the moment, without interpretation or judgment. Practicing mindfulness involves breathing methods, guided imagery, and other practices to relax the body and mind and help reduce stress.”

Diane Elliot, who designs mindfulness elements for Total Worker Health programs, noted that while mindfulness training may enhance cognitive changes associated with chronic stress, traditional mindfulness training requires both time and skilled facilitators.

Dr. Gruppe helped direct a randomized controlled trial of mindfulness training for 114 law enforcement officers from three agencies in Dane County, Wisconsin. Key findings included:

- Mindfulness training leads to lower PTSD symptoms.

- Reduced PTSD symptoms led to improved sleep following mindfulness training.

Conclusion

The 2023 NIJ National Research Conference’s expert presentations on correction officer stress, and mindfulness training as one approach to relieving that stress, reflect the commitment of the National Institute of Justice to research initiatives supporting our nation’s correctional institutions and those who work and reside there.