It is not unusual for victims to find it difficult to engage with law enforcement after experiencing an assault. Often, victims fear they will not be believed or that reporting the crime will not have any effect.

How can law enforcement best help victims engage with the system after an assault? The answer lies in creating best practices for victim contact. Three Department of Justice-funded research projects are looking at this from a variety of new perspectives.

The Problem: Victim Engagement Can Be Traumatic

Sexual assault kits contain crucial evidence. Unfortunately, collecting the evidence contained in them can be intrusive and re-traumatizing for victims who must undergo medical forensic exams soon after their assault, at a time when they may not be ready to report the crime to the police. Despite the importance of collecting semen, blood, saliva, and hair samples contained in sexual assault kits for criminal investigations and prosecutions, evidence is not routinely sent for testing and forensic DNA analysis. Police and crime labs can have large backlogs of untested kits. Delays in testing not only hinder the pursuit of justice but also can perpetuate or exacerbate victim trauma.

Influxes of public money, coupled with persistent public outcry, have prompted many jurisdictions to expedite the processing of their backlogged kits, resulting in the identification of thousands of persons who have committed a crime through hits in the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). But re-opening these cases often happens months or even years after the original crime. Police and prosecutors must contact victims to inform them that their evidence had never been analyzed and that their cases may be reopened, a process that can be deeply re-traumatizing.

Dr. Rebecca Campbell, professor of Psychology at Michigan State University, focuses on understanding the consequences of unprocessed sexual assault kits on victims. Her work studies the prolonged psychological distress and sense of injustice of survivors who have been denied prompt case resolution and closure.

Dr. Campbell knows just how important it is to re-earn survivors’ trust. She previously served as the lead researcher for the Detroit Sexual Assault Kit Action Research Project[1], a four-year multidisciplinary study of untested rape kits, which was funded by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ). In 2009, that research found 8,717 kits in Detroit, Michigan, that had never been sent for testing, primarily due to years of understaffing and insufficient resources.

In her recent research, Dr. Campbell asked, “What do we know and what do we still need to know about re-engagement with victims after a CODIS hit?” She interviewed sexual assault survivors in Detroit, all of whom had kits that had been collected but not sent for analysis. The kits were found in the Detroit backlog, sent for analysis, and selected for victim notification after a CODIS hit. Their legal cases were then re-opened, prosecuted, decided, and closed. Of the 112 survivors who fit the criteria of the study, 32 chose to take part, a testament to how difficult it is for these victims to re-engage about their assault. This may be particularly true when it comes to re-engaging with the system.

“If you break that trust, you have to re-earn it.” – Dr. Rebecca Campbell

Based on study findings, Dr. Campbell advocates for victim-centered approaches and trauma-informed training of law enforcement to improve communication between survivors, law enforcement, and medical professionals. She has also highlighted systemic changes such as policy reforms, increased resources, and enhanced collaboration among agencies who work with victims of violence to tackle the backlog and support survivors effectively.

Describing the program for re-engaging victims, Dr. Campbell said, “The process is the outcome. How people are treated along the way is what matters most.” Her research shows the detrimental effects of untested kits on victims' well-being and underscores the necessity of comprehensive reform. Training is vitally important because it allows departments to change harmful practices and ultimately resolve these cases more successfully with the help of the victims.

Law Enforcement Benefits from Trauma-Informed Training

Dr. Cortney Franklin, assistant professor in the Department of Culture, Society and Justice at the University of Idaho, examines how trauma-informed training of law enforcement affects sexual assault case processing and police response to gender-based violence. According to Dr. Franklin, “We must ask: ‘What can we do to enhance the victim experience?’”

Dr. Franklin’s research on whether mandatory trauma-informed training improved trauma misperceptions and response among police officers was the first of its kind in the United States. She surveyed officers before and after receiving training that covered survivor-centered police response to sexual and domestic violence, neurobiology of trauma, victim resource referral, and gender bias. The training also included routine in-service content on state and federal laws, cultural diversity, investigative topics, and crisis intervention required by the state’s law enforcement commission.

Dr. Franklin examined the degree to which the training increased the accuracy of the officers’ knowledge about trauma. In addition to officers’ self-reported knowledge, her research examined 1200 sexual assault cases to assess if training affected how they were processed and proceeded. In particular, she looked for differences in police response and investigative stages before and after training by evaluating patterns in complainant characteristics (e.g., demographics, credibility indicators, participation decisions), suspect characteristics (e.g., demographics, relationship to the complainant), and case characteristics (e.g., strength of evidence indicators, case seriousness measures).

Dr. Franklin’s research team found that most officers had some misperceptions about what people’s response to trauma looks like prior to training. Some officers endorsed the view that “real” victims present with emotional expressiveness, behavioral hysteria, prompt reporting, and linear recollection of the assault. But this is not accurate, and these myths are dangerous; when a survivor does not display these characteristics, they may be disbelieved and stigmatized, which increases their likelihood of secondary victimization by the system. Officers who took trauma-informed training reported significantly decreased levels of trauma misperceptions after training compared to before. Moreover, the officer’s sex (male or female) and years of service were significant predictors of trauma misperceptions before training. Male officers and officers with less job tenure reported higher levels of trauma misperceptions. Female officers and officers with more job tenure reported increased accuracy of trauma presentation knowledge.

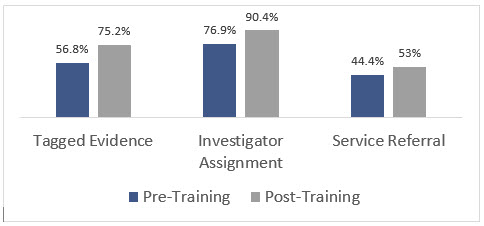

Why do interactions between victims and officers matter? It is in the interest of the police department to improve interactions with victims so that officers do not cause more harm to the victims than what they have already experienced, and so that officers can be a helpful resource to victims. Also, training on better communication and a more empathic response to victims has been shown to strengthen case processing,[2] meaning that post-training cases had more tagged evidence, were more likely to be sent to specialized investigators for follow-up, and had more officers engaged in victim advocacy referrals (Figure 1). Dr. Franklin’s results highlight how trauma-informed training shows promise in advancing survivor-focused police response to sexual assault.

Figure 1. Case file data comparisons show post-training improvements in the percentage of tagged evidence, investigator assignments to cases, and the provision of service referral information (n = 464).

An Unconventional Approach

In related research, Dr. Bradley Campbell, associate professor in the Department of Criminal Justice and a faculty member in the Southern Police Institute at the University of Louisville, studies police investigations, decision-making, training evaluation, and response to victims. Through his NIJ-funded research project, he trained law enforcement on how to interact with trauma survivors and assessed both the short- and long-term impact of that training on the officers and the survivors.

Dr. Campbell trained police officers to respond to victims of violence using victim-centered, trauma-informed (VCTI) interview techniques. His unconventional program used actors who were trained to portray survivors of sexual assault and provided officers with hands-on experience in interviewing techniques. The interdisciplinary team included a unique partnership between the Kentucky Department of Criminal Justice Training, the Kentucky Association of Sexual Assault Programs, and the University of Louisville’s Criminal Justice and Theatre Arts departments.

They taught officers to conduct VCTI interviews with victims during a 40-hour training program. In total, 113 trainees were randomly assigned to a treatment (trauma-informed) or control (standard training) group. Researchers conducted pre- and post- training survey assessments of officers’ attitudes and understanding of the material and capitalized on a unique opportunity to assess officers’ behavioral changes through both within-subjects and between-subjects comparisons of officer performance in mock interviews.

The results showed that VCTI training improved outcomes and positively affected officers. Researchers saw improved perceptions of victim behaviors and increased comfort when interviewing victims of sexual assault. The researchers recommended that all jurisdictions add VCTI training to their curricula. Although this may present a significant investment for many agencies, shorter 16- or 24-hour trainings may also be beneficial. Moreover, trauma-informed interview training with actors may prove beneficial in other ways, for example related to domestic violence cases, traffic stops, and de-escalation.

“The use of trained actors was integral in putting the skills learned into practical application. The actor piece gives interviewers a chance to receive feedback of how the survivor perceived the interaction. Often as interviewers, we may believe we’re making the survivor feel more comfortable or less traumatized, but our wording or body language may actually be hindering our efforts.”

̶ Sergeant Jeremiah Harville, Lexington Police Department, Lexington KY.

Unsurprisingly, law enforcement can find it challenging to encourage survivors of sexual assault to work with them after prior interactions yielded no resolution. But using trauma-informed training techniques — both in repeated contact with survivors and upon first interview — can improve case closure rates and, more importantly, enhance victims’ emotional wellbeing. These efforts also strengthen communities and increase trust in law enforcement, which are critical factors in law enforcement’s effectiveness.

About This Article

This article is based on the following grants:

Rebecca Campbell (2018-SI-AX-0001) Office on Violence Against Women grant.

Bradley Campbell (2018-VA-CX-0003) NIJ grant.

Cortney Franklin (2016-SI-AX-0005) Office on Violence Against Women grant.