We know lawyers can help victims of crime. But we’re still learning what successful legal representation of crime victims looks like in different kinds of cases.

New research supported by the National Institute of Justice identifies a model process to help crime victim legal clinics refine their operations in ways that can work best for clients. The study also offers a roadmap for evaluating whether and how case outcomes are benefiting their crime victim clients in meaningful ways.

Federal law and the legal system have long recognized crime victims’ rights. Starting in the 1970s, legal clinics and other victim services emerged to safeguard those rights. The federal Crime Victims’ Rights Act of 2004 spelled out the rights of crime victims and provided resources to protect them. Before that, the Victims’ Rights and Restitution Act of 1990 required federal agencies to give best efforts to ensure that crime victims are treated with fairness and respect and protected from those who victimized them, among other rights. Most states have adopted their own crime victim protections.

A Conceptual Model for Crime Victim Legal Clinics

Legal clinics helping crime victims have grown out of the recognition that crime victims without legal counsel are often unable to exercise their rights.

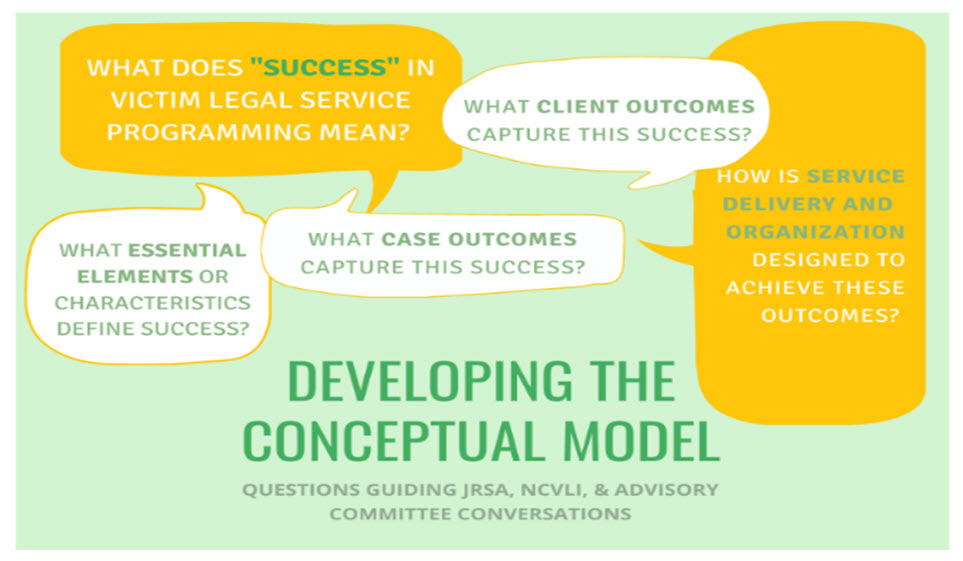

Slowing that progress, however, is uncertainty about (1) how to define success in a legal clinic’s representation of crime victims, and (2) how to apply that definition in evaluating whether clinics have represented victims successfully in particular matters. These are just the types of questions a conceptual model is designed to help answer.

Now researchers from the Justice Research and Statistics Association, partnering with the National Crime Victim Law Institute, have built the first conceptual model for:

- Designing legal clinic operations that can work best for victims.

- Evaluating clinics’ effectiveness in practice.

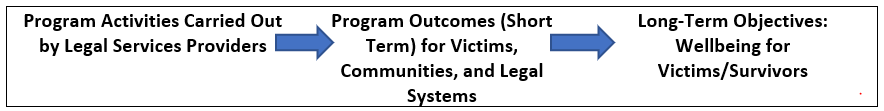

The conceptual model lists program activities carried out by legal service providers, short-term program outcomes resulting from those activities, and the long-term objectives associated with the wellbeing of crime victims. See figure 1.

For crime victim legal clinics, the conceptual model has policy and practice implications for improved clinic operations. For crime victims, it has implications for achieving better personal outcomes.

Successful Legal Representation of Crime Victims Can Take Many Forms

Success, under the model’s framework, isn’t limited to clear-cut wins for crime victim clients — for example, a client victory in a court action for restitution. Instead, success can come in varying degrees and take many forms, depending on the nature of the case. One useful notion of success, informed by the research literature and adopted by the research team, is the idea of lawyers helping crime victims conserve what resources they have — material, emotional, mental, etc. — through trauma-informed services.

Trauma-informed legal services acknowledge the role trauma can play in people’s lives and can help avoid re-traumatizing victims of crime.

Applying trauma-informed services promotes the experience of procedural justice for the victim. Procedural justice is the idea that equitable application of justice and transparency of process promotes fairness and respect and avoids system re-victimization. The four elements of procedural justice are: [1]

- Voice: People want an opportunity in the justice process to tell their side of the story.

- Neutrality: People want to perceive judges and courts as neutral, principled decision-makers.

- Respect: People want legal system actors to treat them and their rights with respect, and to communicate to people that they are viewed as important and valuable.

- Trust: A central factor that influences public evaluations of legal authorities is an assessment of the character of the decision maker.

Figure 2 shows how this all ties together and demonstrates the “theory of change” that underlies the conceptual model. The theory of change suggests that the program activities carried out by legal service providers should lead to short-term program outcomes, which, if achieved, theoretically lead to the achievement of long-term objectives.

Victim empowerment, the research team concluded, is one of the primary benefits of receiving legal services. Trauma-informed services can empower victims, even if a desired legal outcome is not achieved, when clients come out of the process believing they had received another important benefit, such as:

- Feeling trust in the legal process.

- Being treated with dignity and respect.

- Feeling encouraged to participate in the legal process in the future.

Creating a Conceptual Model of Effective Legal Clinic Services for Crime Victims

To build their conceptual model for improving the chances of success for crime victims in the legal system, the research team:

- Reviewed the literature on needs of, and legal services for, crime victims.

- Conducted intensive interviews of service providers and crime survivors.

- Surveyed a national sample of providers.

- Assembled an advisory committee comprised of a broad group of legal services providers and crime survivors. Advisory committee members took part in the research survey and a roundtable discussion.

With that knowledge in hand, the researchers assembled a conceptual model enabling them and the clinics to define desired legal clinic services for victims, short-term outcomes, and long-term objectives.

Formative Evaluation: Applying the Model to Three Victims’ Legal Services Clinics

The researchers then applied the model to three existing legal clinics serving victims of crime to conduct a formative evaluation. The formative evaluation helps clarify each program’s purpose, processes, potential outcome measures, and readiness for separate, more rigorous evaluations of its processes and performance. The three clinics were the Arizona Voice for Crime Victims, the Oregon Crime Victims Law Center, and the Maryland Crime Victims Resource Center.

Other issues the researchers examined that may be common to legal clinics planning an evaluation were:

- Legal privacy concerns

- Staffing and other available resources

- IT issues

The researchers tested the conceptual model at each of the clinics, helping to build a better foundation for determining and monitoring that legal clinic’s fidelity to the model. The formative evaluation also assessed each of the three clinics’ overall readiness for the next phases of evaluation, including a formal process and outcome evaluation to determine whether each clinic was ready and able to assess the degree to which program activities are being implemented as intended and the program is achieving intended outcomes for victims.

In the end, the research team made the assessment that all three clinics were ready to move forward with a process evaluation and with preparation for an outcome evaluation of how each clinic’s legal services were working for crime victims, with some qualifications.

Limitations Faced

In several instances, the researchers found that technology elements of the legal clinics’ operations were not adequate to meet desired program purposes, but that they would be addressed when planned IT solutions were in place.

The research team noted that the COVID-19 pandemic slowed its initial work with the three clinics. (That was true of many research initiatives requiring close interpersonal collaboration during that period.) But they completed enough of the formative evaluation phase to reach an evidence-based conclusion that each of the three clinics was ready for an in-depth process evaluation in preparation for an outcome evaluation.

The research team noted that several advisory committee members and providers “expressed strongly” their concerns that the conceptual model would be challenging to achieve, since victims’ desired outcomes are often not easily accomplished. But the researchers pointed out, in response, that the model was “aspirational” and meant to be used as a guide to design and implement programs, and measure progress.

Other unanticipated legal system “shocks” occurred after the research was under way. They included justice system reforms such as programs to reduce prison populations through compassionate release. (Some compassionate releases were products of the pandemic.) Such reforms affect crime victims’ rights in new ways, the researchers noted. Despite these new shocks, the conceptual model still provides a basis for program design and measurement of outcomes. The research team reported that “all three clinics emphatically declared that their desired victim, community, and system outcomes did not change.”

Conclusion

Developing more effective legal clinics for crime victims requires first understanding what program elements are needed and what success would mean for each client. Rarely do victims of crime experience clear-cut victories through the court (although victim restitution would be a victory). In many cases, success takes on more intangible forms, like feeling respected by the system and having greater trust in the legal process.

This novel conceptual model for victim legal clinics offers a potential new pathway for crime victim legal clinics to align their operations with client needs and improve the prospects for successful client outcomes.

About This Article

The research described in this article was funded by NIJ award 2018-ZD-CX-0005, awarded to the Justice Research and Statistics Association, Washington, DC. This article is based on the grantee report “What Constitutes Success? Evaluating Legal Services for Victims of Crime, Executive Summary,” by Kristina Lugo-Graulich.