Much is known about the workings of criminal gangs and traits of gang members, and much of that knowledge has informed community-focused anti-gang programs. It was long hoped that what works against gangs could also help build community resilience to the emergence of homegrown violent extremists, but recent research suggests that gang members and domestic extremists have too few traits in common for gang programs to translate. The few observed similarities that could point to the possibility of common programmatic solutions are tenuous at best.

A study by a prominent terrorism research center found key distinguishing factors between gangs and domestic extremists, such as average age and marital status, commitment to religious faith, and vulnerability to financial strains versus vulnerability to threats to cultural identity. The University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) empirically analyzed both the quantitative demographic traits of gang members and domestic extremists and certain qualitative differences between the groups. The qualitative study element examined distinguishing factors such as comparative strength of community and family connections and level of reliance on social media.

Quantitative Comparison: Little Overlap

The research, sponsored by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), yielded clear policy implications, according to the research report submitted to NIJ. The quantitative component of the work found:

- Little overlap between extremists and gang members — A finding of a low level of overlap, in terms of both population overlap between gang members and extremists (relatively few individuals were both) and shared traits, offered little support for adapting anti-gang policies and programs to the threat of domestic extremism.

- Significant age differences — Extremists were typically older than gang members by several years, again suggesting to the START team that the prevention, intervention, and suppression strategies deployed against gangs, which tend to be more focused on youth intervention, may be less effective against political extremists.

- Older gang members vulnerable to extremism — Policymakers may expect that, compared with younger gang members, more older gang members will radicalize as they approach the prime age for extremist group activity, especially if they feel they have been treated unfairly by the gang while involved with it.

Qualitative Comparison — Differences Prevail but With Shared Resilience Factors

The qualitative study component yielded key findings that the researchers deemed to be in harmony with the quantitative work highlighting how the two groups differ. The START researchers also identified several factors within individuals and communities that are conducive to resilience to participation in both gangs and extremist groups. Those factors included:

- Value of family and other prosocial relationships.

- Provision of essential needs in disadvantaged communities.

- Development of cognitive resources in responding to individual crises.

The researchers further concluded that tailoring preventive, community-based programming to local circumstances is crucial, “as cut-and-paste efforts could be perceived by communities as insensitive and potentially detrimental toward providing beneficial relationships.”

Study Design

The START study was an empirical assessment of:

- Commonalities between individuals involved in violent extremist groups and gangs.

- The extent to which those empirical results support the use of anti-gang programs to build community resilience to violent extremism.

The four subject samples were:

- A quantitative dataset of U.S.-based extremists.

- A quantitative dataset of U.S. adult and adolescent gang members.

- Qualitative life histories of U.S.-based extremists.

- Qualitative interview data from current and former U.S.-based gang members.

Researchers drew the quantitative dataset of extremists from the Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS), developed with NIJ support.[1] At the time of analysis, PIRUS included individual-level data from 1,473 observed cases of U.S.-based extremism. PIRUS drew data exclusively from open sources such as news media reports, court records, and published biographies.

Qualitative data on extremists were drawn from a PIRUS subset of individuals radicalized to the point of committing violent or nonviolent illegal acts in the United States between 1960 and 2013.

For the quantitative study of gang members, researchers drew data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997, one of the largest publicly available sources of data on gang members. The research team obtained qualitative data on gangs through interviews with 45 current and former gang members in Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Denver.

The START team found limited group similarities that suggested a potential for applying gang program models to extremist groups, but cautioned that the connection is tenuous and more work is needed to confirm an overlap. The similarities related to:

- Group context and group processes.

- Joining, engaging, and leaving.

- Organizational structures.

- The role of women.

- The importance of both symbolic and instrumental activities.

- The role of oppositionality, particularly as it results in violence.

- The potential role of prison in the emergence and maintenance of gangs and extremist groups.

However, the research report stressed that “these parallels are largely speculative despite some attempts to examine the overlap.”

Key Demographic Differences Between Extremists and Gang Members

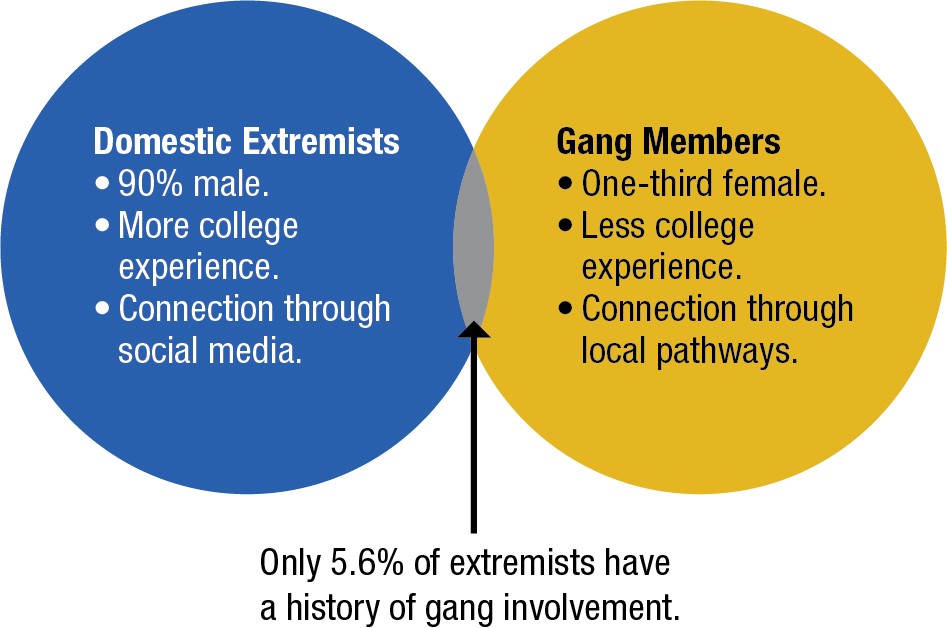

The study revealed distinct demographic differences between extremists and gang members on key measures. For example, the two populations had little overlap: Only 5.6% of extremists had a history of gang involvement. With respect to age, nonextremist gang members were approximately 45% younger than extremists in general, and approximately 40% younger than extremist gang members. Extremists with a history of gang involvement were on average four years younger at the age of group involvement than extremists without a history of gang involvement.

With respect to marital status, extremists were far more likely to be married than gang members generally, a finding related to the large age difference between the two groups.

As for education and wealth, extremists had more college experience than gang members and displayed lower rates of poverty than gang members, in both childhood and adulthood.

Other contrasting traits of extremists and gang members are presented in ( exhibit 1).

| Characteristic | Extremists | Gang Members |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 90% were male. | One-third were female. |

| Race/Ethnicity | Domestic terrorists more closely approximated the overall racial and ethnic composition of the United States. | Gang members more closely reflected the composition of millennials. They were more likely to be Black or Hispanic. |

| Generational Presence in the United States | Gang and nongang extremists were overwhelmingly third or more generation citizens, but nongang extremists were more likely to be first-generation residents than gang extremists. | 79% of all adult gang members were third or more generation U.S. residents, but there was a much greater second-generation presence in gangs. |

| Religion | Survey data from extremists revealed that, before they radicalized, they were less likely than gang members to be associated with no religion, or to be Catholic or Protestant; they were more likely to be Muslim or Jewish. | Gang members were more likely to be Catholic or Protestant |

| Perceived Rewards of Involvement in Gangs vs. Extremist Groups | Extremism was associated with emotional rewards. | Gang membership was associated with material rewards. |

| Different Strains Field by Extremists and Gang Members |

|

|

| Sense of Community and Family Relations |

Extremists were likely to experience a tragic loss of a parent or partner, but for both groups, social bonds were weak. |

Gang members experienced a higher rate of loose community relations and poor family connections than extremists. Gang members’ relationships with parents or guardians were more often fraught, distant, or abusive. |

| Media Use | Nearly exclusive to extremist groups was the use of message boards, forums, or other forms of media, a fact that may relate to the political nature of extremism. | Pathways into gangs were largely local. Gang recruitment is often the product of neighborhood-based ties and friendships. |

Note: The examples in this exhibit are a partial list of those traits discussed in Gary LaFree, “A Comparative Study of Violent Extremism and Gangs,” Final report to the National Institute of Justice, grant number 2014-ZA-BX-0002, August 2019, NCJ 253463.

About This Article

The research described in this article was funded by NIJ award 2014-ZA-BX-0002, awarded to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), University of Maryland. The article is based on the report “A Comparative Study of Violent Extremism and Gangs” (2019) by Gary LaFree.