After many years of examining populations of very small particles on everything from illegal shipments of elephant tusks to carpet fibers in the trunk of a murder suspect’s car, forensic investigators David and Paul Stoney have turned their attention to particles found on shoes. Specifically, they wanted to know if the three different categories of particles found on a shoe – loosely, moderately, and tightly held – could provide a narrative of where that shoe had been.

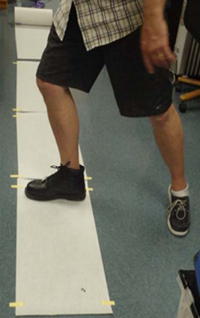

To determine how much such particles could reveal, the two researchers walked through three test environments wearing a total of 36 pairs of shoes – half of them tennis shoes and half work boots. Walks of 250 meters were done at three sites chosen because of their different soil minerals – the Appalachian Trail, the Luck Stone Quarry, and Piney River, all in Virginia. The sites were all dry and dusty and, following each exposure, the footwear was repackaged in its original box between folds of butcher paper.

The project, supported by an NIJ grant, was designed to test the hypothesis that by separately analyzing percentages of loosely held, moderately held, and strongly held particles from a shoe, investigators could detect the sequential exposure of the shoe to different environments. If the hypothesis proved true, an investigator might be able to determine a sequence of where a shoe had been. However, after examining the particles recovered from the test walks, the researchers rejected their hypothesis.

“Under the experimental conditions, the contact surface of footwear was found to be overwhelmingly dominated by the most recent exposure,” the two researchers noted in their summary report. Prior research indicated that some particles that had transferred to different types of trace evidence would be rapidly lost, while some would be retained longer, allowing for a sequential profile of the particles. That is not the case for shoes, they concluded. Walking through the test environments, they wrote, “results in the virtually complete removal and replacement of particles adhering to the contact surfaces from prior, similar exposures.”

The clear implication of the research, they said, is that “although particles on the contact surfaces of footwear [loosely held particles] are removed and replaced, those that are present on the more recessed areas of the sole [moderately and tightly held particles] are not.” That fact does not exclude particle evidence as potentially valuable evidence, they indicated.

“For example,” the researchers said, “in cases where a body is found and may have been transported after death from one location to another, the contact surfaces of the footwear will retain unmixed small particle traces that are directly representative of the last location where the deceased walked.” By examining those particles, investigators can determine if the body was moved and use the particles as clues to locate from where the victim was moved.

On footwear from a suspect, the researcher said, the loose particles will likely not match those from a crime scene and attention should be focused on the more tightly held particles in recessed surfaces. “Recessed areas of footwear are responsible for the mixtures of particles arising from activity before, during and after the crime itself,” the researchers said. Examining particles in the recessed areas could allow researchers to develop a more sophisticated profile of where a shoe has been, although more work is needed to determine if that is scientifically relevant.

About This Article

The research described in this article was funded by NIJ cooperative agreement number 2014-DN-BX-K011, awarded to Stoney Forensic, Chantilly, VA. This article is based on the grantee report "Differential Sampling of Footwear to Separate Relevant Evidentiary Particles from Background Noise" (pdf, 35 pages) by David Stoney, chief scientist, Stoney Forensic.