Archival Notice

This is an archive page that is no longer being updated. It may contain outdated information and links may no longer function as originally intended.

Prepared remarks by NIJ Director David B. Muhlhausen given at CNA Executive Session "Innovative Approaches to Addressing Violent Crime."

Good morning, and thank you for having me here. On behalf of the National Institute of Justice, I’d like to congratulate CNA on the celebration of its 75th anniversary of service. It’s an honor to be here. I’m glad to have the opportunity to share some thoughts on the important issue of violent crime, and how we can go about effectively addressing it.

As CHIPS mentioned, I recently took over as director of the National Institute of Justice. For those of you who aren’t familiar, NIJ is the Department of Justice’s research, development, and evaluation agency. Our mission is clear – we use science to inform and advance criminal justice policies and practices across the country. To accomplish this, we provide objective knowledge and tools to inform the criminal justice community, particularly at the state and local levels.

As many of you know, CHIPS served as the Director of NIJ from 1982 to 1990. Long before I ever entertained the thought of becoming the Director of NIJ, I once read that some consider the 1980s to be the heyday of NIJ’s influence. To those of you who know CHIPS, this conclusion comes as no surprise. I greatly appreciate his advice and knowledge and am honored to call him a friend.

As you can imagine, thinking about violent crime and how it can be addressed is an important part of NIJ’s mission and research portfolio.

Current Landscape of Violence Crime

Today’s discussion about violent crime is a timely one for a few reasons. Combating violent crime is a key priority of Attorney General Jeff Sessions. The issue is closely tied to ongoing discussions surrounding the need for police officers to have the equipment and other necessary resources to keep the public and themselves safe. And over the past month in particular, violent crime has been in the media spotlight.

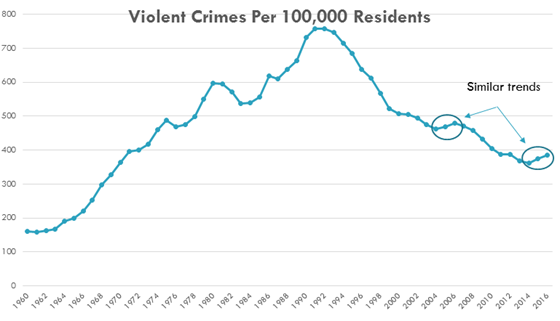

Source: FBI, Crime in the United States, various years.

As many of you know, the FBI released statistics last month that showed that violent crime, including homicide, had increased for the second consecutive year in 2016. Obviously we don’t know 2017 statistics yet, but a Major Cities Chiefs Association survey found a 3 percent increase in homicides in the first six months of 2017, as well as nearly 4,000 more aggravated assaults in the first six months of 2017 compared to the same period the previous year.[1]

As can be seen in the chart, the nation has previously experienced a two-year increase in violent crime that was not sustained in the third year. We ultimately do not know if violent crime rates will increase, flatten out, or decrease in 2017.

However, the recent pattern is alarming. In response to violent crime, Attorney General Sessions has announced several initiatives aimed at reducing gun violence, illegal drug sales, and combating gangs. The current administration has called for the police to increase arrests, and for prosecutors to be more aggressive in their charging decisions.

Of course, the rise in certain violent crime rates is not a uniform trend across the country. We see larger increases in Baltimore, Chicago, and Las Vegas than, say, San Francisco, Washington, and Boston.

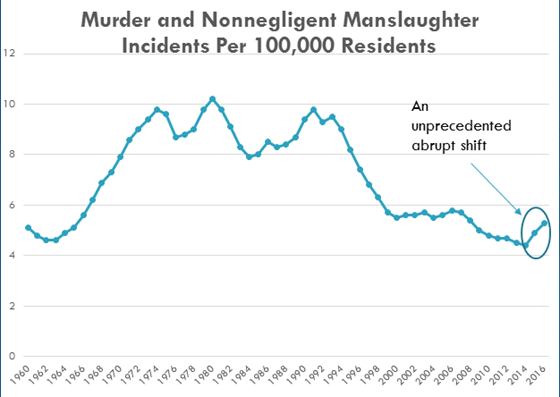

Source: FBI, Crime in the United States, various years.

But we do know that nationally, violent crimes increased more than 4 percent last year, and homicides increased almost 9 percent. We know that these increases follow 2015 trends of nearly a 4 percent jump in violent crime, and more than 10 percent increase in homicides. Current trends are still lower than those we saw a decade ago. National crime rates remain well below the peaks reached in the 1990s, but the recent rise in violent crime over the past years is a cause for serious concern.[2]

In fact, the abrupt increase in the murder rate over the last two years is unprecedented. Since 1960, we simply have not seen such a sudden shift in the murder rate.

My goal here is not to speculate on the causes of the increase in violent crime we’ve seen over the past years, and continue to witness this year. My goal is to consider how we can most effectively address the issue of violent crime, to the ultimate end of reversing this trend.

Need for Evaluation: Learn What Works, Fund What Works

At NIJ, we’re interested in funding research that informs how we can best direct resources to combat violent crime. Ultimately, this comes down to a question of rigorous evaluation of program effectiveness. I want to know what works in combating violent crime. I want to know what doesn’t work. As a researcher, I also want to know what shows promise and begs further study.

Given scarce state and local government resources, policymakers need to fund criminal justice programs that work and defund programs that don’t.

It’s a simple concept—keep doing what works and stop doing what doesn’t. But many programs in place to combat violent crime are not based in evidence. I have a background in program evaluation and statistical methods. As the new director of NIJ, I’m a huge advocate for rigorously evaluating programs to understand their effectiveness.

Basically, the evidence-based policy movement works to inform policymakers through scientifically rigorous evaluations of the effectiveness of government programs. It provides tools to identify what works and what does not work. This task is particularly important in the field of criminal justice. We don’t need to go any further than the FBI statistics released last month to remember that in criminal justice, the stakes are human lives.

We need to make funding decisions based on scientifically rigorous impact evaluations of programs. These evaluations are vitally important. There is no merit in continuing well-intentioned criminal justice programs that fail to prevent or reduce crime. Resources should be shifted away from programs that do not work and towards programs with demonstrated success. As Director of NIJ, I feel that rigorously evaluating the effectiveness of criminal justice programs is the agency’s most important mission.

This mission means that I am a strong proponent of randomized controlled trials, or RCTs. RCTs are the only way to determine the effectiveness of criminal justice programs with the highest degree of certainty.

RCTs, which use random assignment to allocate subjects to treatment and control groups, are the “gold standard” of evaluation designs. Random assignment helps to ensure that the control group is equivalent to the intervention group in composition, predispositions, and experiences. Properly done RCTs have the highest degree of internal validity.

Rigorous impact evaluations that use RCTs provide policymakers with improved capability to oversee criminal justice programs and protect the public. Can RCTs be done under all circumstances? Of course not. But given the superiority of RCTs in demonstrating causality, I firmly believe that we should do them wherever and whenever we can.

Replication and the Single-Instance Fallacy

Another important mission of NIJ under my leadership will be attempting to replicate and scale-up the results of effective criminal justice programs. If an innovative program appears to have worked in one location, it doesn’t mean that the program can be effectively implemented on a larger scale or in a different location. Proponents of evidence-based policymaking should not automatically assume that funding programs that attempt to replicate previously successful findings will yield the same results. What works in Tulsa, Oklahoma, may not work in Baltimore, Maryland.

The faulty reasoning that drives this overgeneralization is called the “single-instance fallacy.” This fallacy occurs when we believe that a small-scale program that appears to work in one instance will yield the same results when replicated elsewhere. Compounding the effects of this fallacy, we often don’t truly understand why an apparently effective program worked in the first place. For example, the dedication and entrepreneurial enthusiasm of a program’s founder may be difficult to quantify or duplicate. How can we know whether we can replicate success elsewhere?

The Minneapolis Domestic Violence study is a perfect example of a program evaluation falling prey to the single-instance fallacy. The study was conducted in the 1980s, and found that mandatory arrest resulted in significantly lower rates in domestic violence.

Although the project researchers urged that the findings be taken with caution, numerous police departments implemented the approach.

However, RCT replications found different results. In Omaha, Milwaukee, and Charlotte, the mandatory arrests resulted in long-term increases in domestic violence, which was the opposite of the policy’s intention.

Another example is Hawaii's Opportunity Probation with Enforcement, otherwise known as HOPE. HOPE is an intensive supervision program that attempts to reduce crime and drug use while saving taxpayer dollars spent on jail and prison.

HOPE focuses on probationers with histories of drug use that are at high risk of failing probation or returning to prison. Many of you may already know about this innovative program because it has received a lot of attention by the media and criminal justice reform advocates.

This court-based program begins with a warning hearing in front of a judge, who sets clear expectations of compliance to the probationer. If the probationer violates his or her probation conditions, each violation results in an immediate brief stay in jail. The premise is that swift and certain punishment is more important to deterrence than the severity of the punishment.

A 2009 single-site RCT, funded by NIJ, found, after one year, that the treatment group was less likely to be arrested for a new crime, less likely to use drugs, and less likely to have their probation revoked than those on regular probation. I must admit that this approach seems to have a lot of promise. It made sense to me, but I withheld judgment because of the single-instance fallacy.

Can the results of HOPE be replicated? NIJ funded a multisite RCT, called the “Honest Opportunity Probation Enforcement Demonstration Field Experiment.” It attempted to replicate the original HOPE effects in four locations in Arkansas, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Texas.

Overall, this large-scale RCT found that the HOPE model was not associated with significant reductions in arrests and was unlikely to yield cost savings. Does this replication mean that all Swift and Certain punishment approaches will fail. No. But it means we must be careful about overgeneralizing the effectiveness of models based on single-site evaluations.

Replications and multisite evaluations such as the HOPE multisite replication provide a way to avoid the single-instance fallacy. Large-scale RCTs conducted at multiple sites allow researchers to avoid making simplistic generalizations based on the findings from single-site studies.

If a program model can’t be successfully replicated, then we need to be cautious about adopting the model more widely. Because of the single-instance fallacy, we should only deem programs as “evidence-based” after they have been found by RCTs to have consistent effects that meaningfully reduce crime in at least three different settings. Once a program model has been found to produce meaningful results in multiple settings, the likelihood of its successful replication elsewhere increases significantly.

This is a high standard to meet. But public safety, in my view, is the single most important activity of state and local government. Charged with such a vital responsibility, our standards should be high.

NIJ Research Portfolio on Violent Crime

At NIJ, we support research that strives to understand and reduce the occurrence and impact of violent crimes.

NIJ has an ongoing and long-standing focus on reducing violent crime. We advance this priority through multiple interrelated research portfolios that address topics like firearms violence, intimate partner violence, terrorism, and gangs. Each research portfolio includes a blend of scientific studies that are designed to produce practical knowledge to help reduce violence. We fund research to identify the causes and consequences of violent crime, and we support scientific evaluations to develop and identify the most effective responses to violence.

NIJ also supports a body of research and development work related to technology and investigative and forensic practices that enhance the capabilities of law enforcement and other criminal justice professionals to respond to violent crime.

The scope of NIJ’s work on violent crime is too extensive to summarize in this talk. But I will briefly mention a few examples of NIJ-funded work on violent crime.

During the 1990’s and 2000’s, NIJ supported a series of projects that developed, evaluated, and replicated targeted deterrence approaches to reducing firearms violence. Targeted deterrence has become a widely recognized, innovative approach that has since been adopted by communities across the nation.

NIJ’s research on intimate partner violence is carried out in partnership with the Office on Violence Against Women. This research portfolio has produced important practical recommendations for improving law enforcement response to domestic violence situations.

Our terrorism portfolio has produced unique databases that help us better understand how people radicalize and become involved in terrorism. NIJ funds a database of individuals radicalized in the United States, which includes data on U.S. incidents dating back to the 1940’s. Another NIJ-supported database focuses specifically on terrorism-related crimes inspired by the Salafi-jihadist ideology. Together, these databases allow for studies of the precursors to terrorism that were previously impossible. These databases and our other counterterrorism and domestic radicalization research allow us to better understand the possible “off ramps” to the radicalization process. That understanding may help us prevent terrorist acts from ever occurring.

What Works in Policing

The issues of policing and violent crime are linked, for obvious reasons. I want to transition now to a brief discussion on NIJ’s work regarding what works in policing in terms of violent crime.

Over the last few years, we’ve seen numerous high-profile incidents across the nation that have illustrated the dangers and challenges of policing in the United States, particularly related to violent crime.

This year NIJ awarded more than $10.7 in funding to support research on policing practices and policies, including how they apply to violent crime. Also this year, we published our Policing Strategic Research Plan, which provides priorities to guide our current and projected efforts to advance policing practices in the United States over the next five years.

The challenges facing police officers today require evidence-based research that will advance police operations and practices. Our strategic policing plan describes how NIJ will support research to provide police with knowledge and tools. This will allow them to support their workforce, promote better policing practices, protect officers, and support effective strategies designed and implemented to fight crime.

One of the biggest tools that NIJ offers police and other criminal justice practitioners is CrimeSolutions, which provides a systematic, independent review process and evidence ratings of justice programs to answer the question: does it work?

CrimeSolutions recently hit a big milestone — 500 rated programs. That’s 500 opportunities for criminal justice and victim service practitioners and policymakers to learn about what works, what doesn’t, and what’s promising.

CrimeSolutions has rated many programs effective or promising, including hot spots policing programs in St. Louis and Jersey City, body-worn cameras in Rialto, California, directed patrol in St. Louis and Indianapolis, and programs combating violence and drug-related crime in Philadelphia, Newark, and Richmond.

It’s worth noting that Chip Coldren and his research team at CNA just completed a study on body-worn cameras that included an RCT component. This study makes a great contribution to the current body of research on this timely issue.

The area of procedural justice has also received considerable attention recently. NIJ provided funding for an evaluation of the Seattle Police Department’s procedural justice program, leading to a number of promising findings.

Another program evaluation in St. Louis examined the impact of hot spots policing and problem-oriented policing on police legitimacy.

The Police Foundation’s assessment of the benefits and risks of various schedules on officer performance is another example of important policing research.

All of these programs, and many others, are examples of ways that a commitment to rigorous evaluation can help police effectively address violent crime.

Conclusion

In all our work, NIJ strives to ensure that our research answers the most pressing needs and questions in the field. These are questions that think-tanks like CNA and sessions like today’s help bring up. We aim to fund relevant research that informs policies and practices centered on what works. As I mentioned before, when it comes to the criminal justice system, and especially violent crime, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

I want to thank you again for having me today. I appreciate the opportunity to talk about NIJ’s work in violent crime and policing. While I was looking forward to the panels, I have to leave early to attend an important meeting. So I apologize for leaving early.

Again, thank you very much for the opportunity to speak today.

[note 1] Major Chief's Association, Violent Crime Survey - National Totals, January 1 to June 30, 2017 and 2016 (pdf, 4 pages), July 31, 2017.

[note2] Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2016 Crime in the United States, Violent Crime.