Home | Glossary | Resources | Help | Contact Us | Course Map

Aviso de archivo

Esta es una página de archivo que ya no se actualiza. Puede contener información desactualizada y es posible que los enlaces ya no funcionen como se pretendía originalmente.

Weight, Force, and Their Measurement

Weight is a way of expressing the force of gravity on an object, assuming certain standard conditions, such as being at sea level. It is a convenient reference standard for firearm examiners and other forensic scientists.

The beam balance is one of the earliest devices used to obtain weight measurements. This instrument was used in a very simple way: by establishing a balance between a questioned weight and known or standard weights. Precision laboratory beam-style balances are sensitive and expensive. They are rapidly disappearing from most forensic laboratories and are being replaced by digital and electronic scales.

Digital Scales

Today, examiners use a digital (electronic) scale to weigh small objects, such as bullets or bullet fragments. These instruments offer advantages over previously used technologies, including convenience, cost, speed, and accuracy.

Several components typically found in digital scales include

- multiple strain gauges,

- a load cell,

- a signal amplifier,

- a specialized microprocessor with built-in proprietary software.

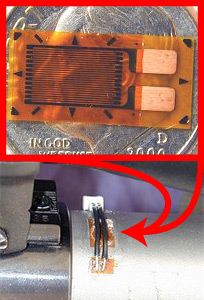

A strain gauge is a paper-thin device that normally covers an area less than that of a dime. It can be permanently affixed to a metal surface to detect stretching or compression; the electrical resistance of the gauge changes with the stretching or compression of the metal surface.

With the exception of the microprocessor, all of the technology used in digital scales has existed for many decades. When microchips became available, the digital scale was a natural development. The proprietary software (built into the microprocessor) processes the data initially provided by the strain gauges, providing stable and useable readings.

Calibration

Instrument calibration involves determining the difference (if any) between the output reading produced and a known standard, and remedying that difference. For digital scales, this means ensuring that the microprocessor correctly relates the amplified digital output signal to a standard weight. Manufacturers of the digital scales most commonly used by firearms examiners provide both known weights (usually not NIST traceable) and detailed but simple instructions for calibration. Calibration takes only a few minutes to perform but is necessary to ensure the accuracy of results.

Changes in heat and humidity as well as unlevel working surfaces can affect the readings of a digital scale by slightly shifting the zero point. Rough usage and power surges can cause harm to a digital scale.

Calibration of a digital scale is simple to perform. However, NIST traceable weights for calibration are a requirement of ISO/IEC 17025:2005 accredited laboratories.

Additional Online Courses

- What Every First Responding Officer Should Know About DNA Evidence

- Collecting DNA Evidence at Property Crime Scenes

- DNA – A Prosecutor’s Practice Notebook

- Crime Scene and DNA Basics

- Laboratory Safety Programs

- DNA Amplification

- Population Genetics and Statistics

- Non-STR DNA Markers: SNPs, Y-STRs, LCN and mtDNA

- Firearms Examiner Training

- Forensic DNA Education for Law Enforcement Decisionmakers

- What Every Investigator and Evidence Technician Should Know About DNA Evidence

- Principles of Forensic DNA for Officers of the Court

- Law 101: Legal Guide for the Forensic Expert

- Laboratory Orientation and Testing of Body Fluids and Tissues

- DNA Extraction and Quantitation

- STR Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Communication Skills, Report Writing, and Courtroom Testimony

- Español for Law Enforcement

- Amplified DNA Product Separation for Forensic Analysts